LAUSD Overhauls $120 Million Black Students Program After Activists File Complaint

LAUSD has altered the criteria for its Black Student Achievement Plan in response to a federal complaint by a conservative Virginia group.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Los Angeles Unified has revised its leading effort to boost academic outcomes for Black students after conservative Virginia-based activists filed a civil rights complaint, charging the program uses race as a criteria for admission.

The district’s $120 million Black Student Achievement Plan had a clear goal: lifting the academic performance of Black students, who trail behind other groups in assessments of reading and math, providing students extra tutors, and added training for their teachers.

The program is now in doubt after Arlington-based Parents Defending Education filed a civil rights complaint arguing it violates federal law by using race “solely” as a criteria for admission, prompting the district to change its policy.

“At bottom, the Black Student Achievement Plan and its benefits are open to some students but not others — and that exclusion is solely based on an individual’s race,” the group’s complaint said.

In response, LAUSD said it’s no longer using race as a factor in choosing which schools participate. But the program’s future remains murky even with the changes because it could still be open to future legal challenges.

Still, it’s a dramatic turn of events for LAUSD’s signature Black initiative, and shows the powerful influence out-of-town interests can have on local policy.

LASUD officials said the district will still give BSAP the same resources as previous years and its programs are staying the same; and all students — not just Black students — are eligible for the help.

The five-year-old BSAP had seemed to be headed for success by targeting Black kids.

With broad support from LA Unified’s board, teachers and families, the program deployed counselors and social workers at roughly 50 schools, which together enrolled more about a third of the district’s Black students.

And this year, the district’s Black students made gains on math and reading tests that outpaced those of other student groups. The district’s Black students also this year outscored Black students around the state on the annual exams.

Since PDE filed its complaint, superintendent Alberto Carvalho said LA Unified was “able to reformat the program without sacrificing impact.”

“Our solution is one that preserves the funding, the concentration of attention and resources on the same students and same schools,” he said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.

Representatives for PDE, which has lodged more civil rights complaints against at least ten other school districts around the nation, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A website for the non-profit says it is a “national grassroots organization working to reclaim our schools from activists promoting harmful agendas,” including critical race theory and restorative justice.

PDE’s board includes Edward Blum, the conservative litigant who previously founded an organization that won a 2023 Supreme Court decision against Harvard University to strike down affirmative action in college admissions.

In its complaint with the federal Office for Civil Rights, PDE argued the BSAP violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by using race to decide which students get extra educational services.

After LA Unified dropped race as an official factor in those decisions, OCR dismissed the group’s complaint, heading off a potential legal battle. But PDE could revive its complaint.

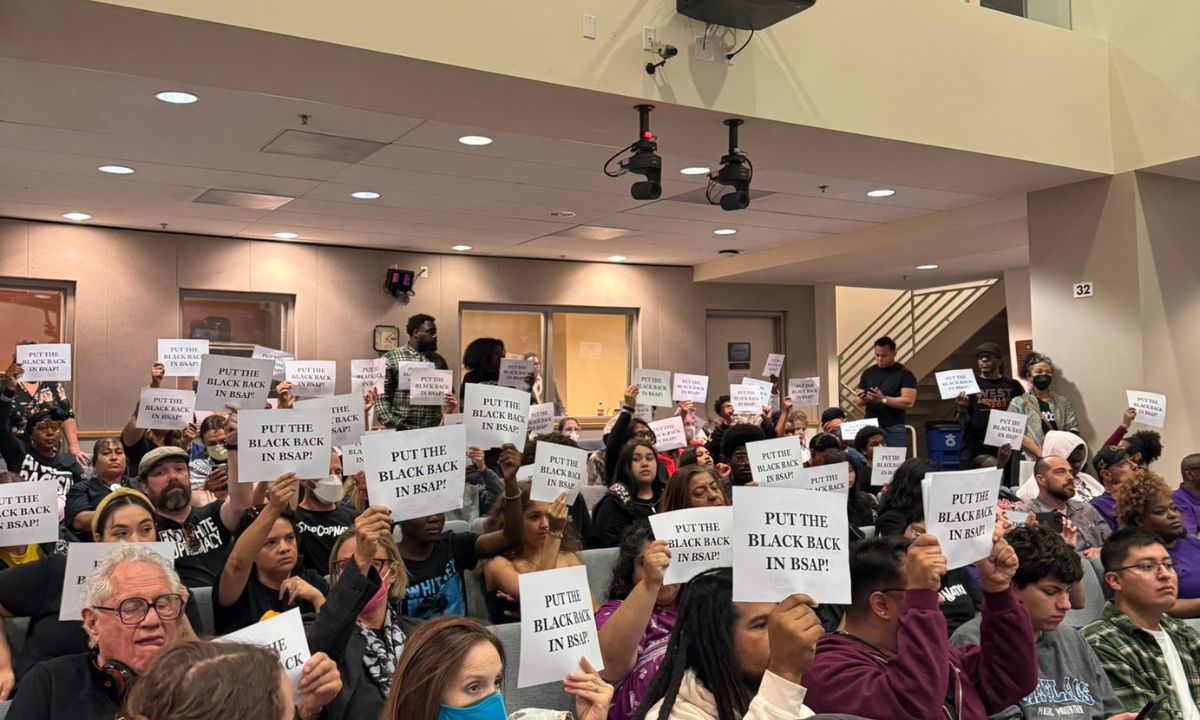

The district’s strategy has drawn fire from its teachers union, activists and students who protested an Oct. 22 board meeting. An online letter-writing campaign urges LA Unified to “reinstate Black student population as a criterion for BSAP school allocation.”

Without race to guide which schools participate in the BSAP, University of Southern California education professor Julie Slayton said LAUSD will have to use other factors in deciding how to distribute extra resources to students.

“They’ll take away the language of ‘Black,’ ” Slayton said. “But it doesn’t have to change, profoundly, the way that they’re thinking about the distribution of these resources and the schools that will receive them.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)