It’s Back to School for Cyber Gangs, Too

Districts from suburban Washington, D.C., to rural Alaska become ransomware victims amid surge in hacks on K-12 districts.

As a new academic year begins, a school district in an affluent Washington, D.C., suburb is rolling out stringent security measures, including metal detectors and a clear backpack mandate, to keep danger from entering its buildings.

Yet even before the first class started, the 133,000-student district in Prince George’s County, Maryland, faced an assault on its security — one carried out completely online.

Rather than barge through the front entrance of a school, threat actors appeared to break in through a backdoor in the district’s computer network. The mid-August intrusion meant the high-performing school system — among the nation’s 20 largest — joined a growing list of school district ransomware victims, another proof point that the education sector is now a primary target of cyber gangs.

“Schools have this delicious trove of data and do not have the same protections” as banks and other for-profit businesses, said Jake Chanenson, lead author of a recent University of Chicago report on school district cyber risks.

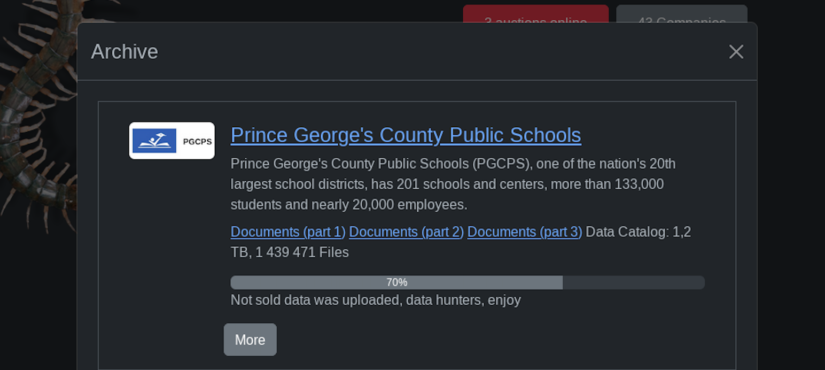

In the case of Prince George’s County Public Schools, the attack appeared to enter its final stage on Tuesday when the Rhysida gang posted to its leak site a collection of data it purportedly stole nearly a month ago. A cursory review of the files suggest they date back two decades.

The back-to-school season, already a particularly busy period for school technology leaders, has become a prime time for district ransomware attacks, according to cybersecurity experts. In August alone, ransomware gangs claimed new attacks on 11 K-12 school systems, according to an analysis by The 74 of the cyber group’s dark web leak sites. Among them are three New Jersey districts, two in Washington state, a Denver charter school network and a district in remote Alaska. Several additional districts have disclosed cyberattacks since the start of the new year, including news of a breach last week against Florida’s Hillsborough County Public Schools, the seventh-largest district in the U.S.

In Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, district officials said a ransomware attack had forced them to cancel classes for three days in just the second week of the academic year.

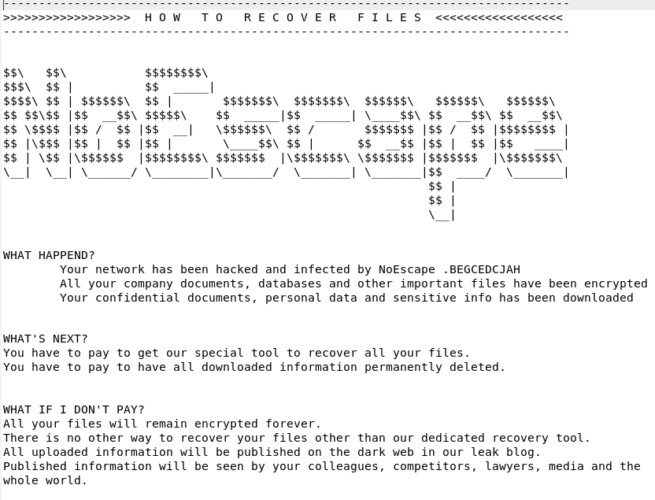

At the Lower Yukon School District in Alaska, technology director Joshua Walton said a hack and subsequent data breach by the burgeoning ransomware gang NoEscape was first initiated in late July, before the fall semester began.

“Your confidential documents, personal data and sensitive info has been downloaded,” the group wrote in a ransom note obtained by The 74. “Published information will be seen by your colleagues, competitors, lawyers, media and the whole world.”

Ultimately, the district refused to pay the group’s $300,000 ransom demand, leading to a small data breach that doesn’t appear to include sensitive information about educators or students. Rather, an analysis of the leak suggests stolen files center primarily on campus maintenance work.

Previous data breaches following district ransomware attacks, such as the ones in Los Angeles and Minneapolis, have led to widespread disclosure of sensitive information, including student psychological evaluations, reports of campus rape cases, student discipline records, closely guarded files on campus security, employees’ financial records and copies of government-issued identification cards.

Though Walton was confident that similarly sensitive records had not been stored on the breached computer server, he told The 74 the Lower Yukon hack could have been far more disruptive had it been carried out just a few weeks later. Instead, they had a few remaining weeks of summer to restore their systems before their nearly 2,000 students returned.

“It was an inconvenience for sure, but I’ve seen a lot of data breaches over the years and ours is nothing comparable,” Walton said. “I couldn’t imagine that happening when school starts because we’re all rushing to get all of the support tickets taken care of and making sure that school is starting off on the right foot. If it would have happened then, it would have been a whole different ball game.”

This year, the return-to-school season kicked off with a warning from federal law enforcement about the growing threat that cyberattacks pose for school districts. During a cybersecurity summit at the White House in early August, federal officials warned the coming months could be particularly volatile. Harm isn’t limited to victim districts but rather encompasses their employees, students and families whose sensitive records, including financial information, are vulnerable to data breaches.

WIth “Social Security numbers and medical records stolen and shared online,” such attacks have left “classroom technology paralyzed and lessons ended,” First Lady Jill Biden said. “So if we want to safeguard our children’s futures, we must protect their personal data.”

There isn’t any hard data on the frequency that ransomware groups exploit back-to-school season compared to other times, said Doug Levin, the national director of the K12 Security Information eXchange. He said it’s also difficult to identify when attacks first begin, with threat actors sometimes infiltrating district servers months before the ransomware attack is initiated. That said, the existing evidence suggests about a quarter of cyber incidents affecting school districts appear to occur during those first few weeks and months of school. He said the chaos of getting technology into students’ hands and setting them up with new online accounts creates an ideal opportunity for criminals to catch district tech officials off guard.

“With all of these new devices being deployed with all sorts of new tools and applications coming online, I certainly have heard reports of upticks in phishing attacks against school districts already,” Levin said. “It’s definitely a time where you know people are more likely to make mistakes.”

Similar concerns were included in a notice last month by the New Jersey Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Cell, where officials warned that cybercriminals routinely exploit holiday breaks to target schools.

“Threat actors take advantage of this pastime when staff is away or just prior to busy seasons, such as the beginning of the school year, long weekends or before the end of a marking period when final grades are due,” the warning notes. “Within the last few weeks, publicly announced ransomware attacks sharply increased.”

‘Exclusive, unique and impressive’

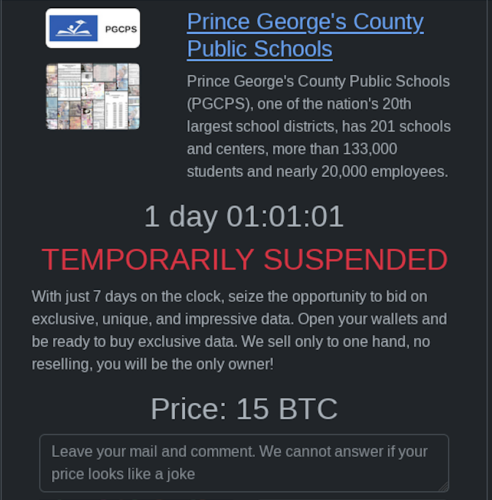

Following a common ransomware playbook in Prince George’s County, the Rhysida gang claimed the theft of sensitive documents, posting screenshots online showing birth certificates, passports and other records purportedly stolen from the district. Unless the district agreed to pay the group 15 bitcoin worth some $375,000, Rhysida threatened to publish the “exclusive, unique and impressive” data on its leak site.

Such negotiations appeared to expire by Tuesday morning: A trove of files purportedly stolen from the district were published to the cyber group’s leak site, suggesting education leaders had refused to pay the ransom. The development comes after a ticker on the gang’s leak site, meant to signify the district’s approaching ransom payment deadline, was paused or delayed on several occasions.

A day after the district detected the breach on Aug. 14, it said in a statement that some 4,500 user accounts out of 180,000 were affected, forcing district employees to reset their passwords. Impacted individuals, the district said, “will be contacted in the coming days.”

The school system is “offering free credit monitoring and identity protections to all staff,” district spokesperson Meghan Gebreselassie said in an email Tuesday morning but declined to comment further. In a Sept. 1 update, the district said staff, students and their families would receive a year of free credit monitoring and identity protection services, acknowledging the attack “may result in unauthorized disclosure of personal information.”

“We are working diligently to confirm the extent of information that was impacted by this incident, and we will move quickly to provide direct notice to those who are impacted once this determination is made,” the statement says.

Yet special education advocate Ronnetta Stanley said the Prince George’s district hasn’t done enough to keep the community in the loop about the attack and its potential effects on students and parents. The types of information that may have been breached, she told The 74, “has not been clearly communicated.” Special education records, which have been exposed in previous attacks like the one against the Los Angeles Unified School District near the start of the 2022-23 school year, could be at risk in Prince George’s County, she fears.

“There have not been any specific details about exactly what was breached, who may have been affected by it and, then what is the remedy for what should be happening with compromising information?” said Stanley, founder of the special education advocacy group Loud Voices Together. “Not knowing what was leaked and who was affected, it’s difficult to say what the ramifications will be.”

The recent risk report by the University of Chicago researchers found that district leaders are frequently unaware of the peril that cyber gangs pose, often implement education technology tools without considering privacy implications and routinely endorse digital tools that present potential privacy issues. While banks and large corporations have become harder targets as they bolster their cybersecurity defenses, schools have fallen behind, said lead author Chanenson, a doctoral student studying computer science.

“This is only going to get worse,” he said, “until we give schools the resources they need to up their defensive game.”

Ransomware’s long tail

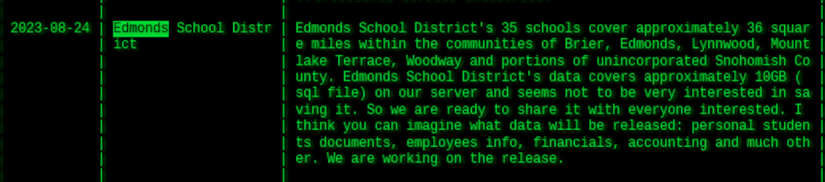

Among the school districts listed on ransomware gang leak sites in August is the one in Edmonds, Washington — a development that for locals may feel like déjà vu. The Akira group named Edmonds as being among its latest victims on Aug. 24, just six months after district officials announced that a “data event” was to blame for a two-week internet blackout in late January.

Data stolen in the winter 2023 breach, the district warned in February, could include names, Social Security numbers, student records, financial information and medical documents. The district is still analyzing the extent of the attack and plans to notify affected individuals once their review is finalized, district spokesperson Harmony Weinberg said in a Sept. 8 email to The 74.

It’s unclear, however, whether the district was victimized a second time this summer, a development officials deny. Cybercriminals routinely target victims on multiple occasions — especially those that pay ransoms to retrieve stolen files. In Edmonds, the district recently became “aware of a public allegation by the group believed to be responsible for our winter 2023 data security incident,” Weinberg said.

“We reviewed the district’s network systems in relation to this data security incident, and found no evidence that any systems were infected with ransomware,” Weinberg continued. “Further, we are not aware of any malicious activity occurring within our network systems since the winter 2023 event.”

Meanwhile, the Los Angeles and Minneapolis school districts continue to grapple with the fallout from cyberattacks that crippled their systems last school year and led to the widespread data breaches of sensitive records about students and educators. After the Los Angeles district was targeted in a back-to-school ransomware attack over Labor Day weekend last year, the nation’s second-largest school system kicked off this school year by announcing plans to borrow $166 million to bolster its cybersecurity defenses.

Seven months after Minneapolis Public Schools fell target to a cyberattack that it euphemistically called an “encryption event,” tens of thousands of individual victims are just beginning to learn their sensitive records were compromised as community members blast education officials for leaving them in the dark about key details.

On numerous occasions over the last several months, educators have complained to district officials that they were being targeted by fraudsters, according to email records obtained by The Daily Dot. “I had my bank account drained last week and had $3 to my name,” one person wrote in an email to Minneapolis schools. Another individual reported getting hit with a fraudulent $2,500 charge on a credit card, while parents reported receiving emails from unverified senders related to their children’s college financial aid.

In a Sept. 1 update on the Minneapolis district website, a breach notice said school officials undertook a “time-intensive” review to determine what information had been stolen, which included names, Social Security numbers, financial information and medical records.

“Although it has been difficult to not share more information with you sooner, the accuracy and the integrity of the review were essential,” the district notice notes. Meanwhile, a “summary report” released last week by the law firm Mullen Coughlin stated that the district had provided written notices to more than 105,000 people whose personal information had gotten caught up in the attack.

The documents were Minneapolis Public Schools’s first public comments on the attack since April 11.

Such disclosures often fall short in providing victims enough information to keep themselves safe, said Marshini Chetty, a University of Chicago associate professor focused on privacy and cybersecurity.

“Disclosure is not enough because people may not fully realize what could actually happen and how their data can be misused,” Chetty said. While victim districts routinely offer credit monitoring and other tools to mitigate financial crimes and fraud, she said it’s more challenging to remedy situations where sensitive information, like medical records or student disciplinary records, are disclosed.

“A lot of times schools are reactive rather than proactive,” she said. If district leaders aren’t doing enough to protect the data from being stolen in the first place, “then it’s almost too late.”

Sign-up for the School (in)Security newsletter.

Get the most critical news and information about students' rights, safety and well-being delivered straight to your inbox.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter