The start of the school year in Oklahoma would have tested the mettle of even the most battle-hardened leaders.

The state’s Republican attorney general twice accused Superintendent Ryan Walters of ignoring laws on spending and transparency, actions he called “deeply troubling.” Members of Walters’s own party said he’d fallen down on his responsibility to get funds to school districts on time. And a series of media reports pointed to his role in a botched release of state test data: While it appeared student performance had skyrocketed, in reality the state had dramatically lowered the bar for success.

But if Walters was feeling the heat, it didn’t show.

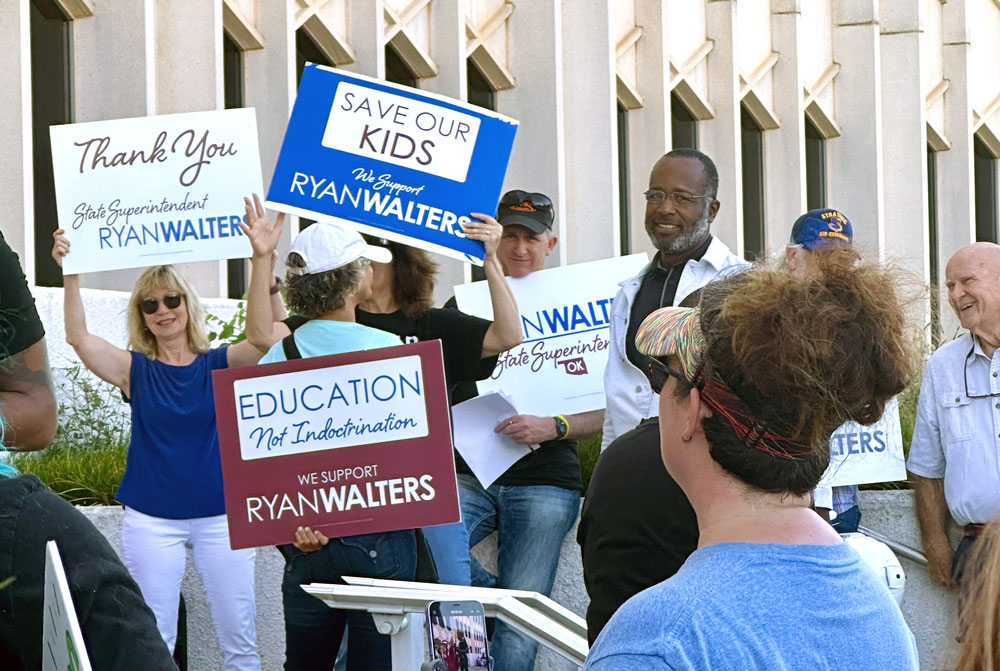

On the morning of Aug. 22, a phalanx of supporters waited for a chance to congratulate him for his headline-grabbing push to put a Bible in every state classroom. One even brought him a gift — a paperback copy of 100 Bible Verses That Made America.

“We raise you up in prayer all the time,” another told him. “I thank you for what you’ve done.”

Taking his seat in the cramped state Board of Education chambers, the 39-year-old Walters picked up a coffee mug with a Latin phrase that evoked his days as a small-town history teacher: Si vis pacem, para bellum. “If you want peace, prepare for war.”

In his 21 months as state chief, Walters has taken the battle to an array of foes. He labeled the state teachers association a “terrorist organization,” blocked reporters from press conferences and moved to suspend the licenses of “woke” teachers. He’s acted as a one-man publicity machine, a performance that’s earned him venomous foes and ardent fans who follow him with a near-religious fervor.

But in his focus on the culture war, his tenure has eschewed many of the mundane, unglamorous tasks of a typical superintendent. By summer, it appeared that one casualty of this approach might be a functional state education bureaucracy. Some pointed to inattention from Walters and the exodus of at least two dozen top officials for a series of damaging missteps, from having to return over $1 million in grant money to the federal government to keeping districts in suspense about funding for low-income students.

Walters, who did not respond to requests for an interview, is used to fielding barbs from Democrats. But increasingly, he’s under fire from fellow Republicans.

The most visible sign of GOP impatience is an investigation sparked by House Republicans into whether Walters misappropriated state and federal funds.

“Regardless of party, citizens want transparency, accountability and communication,” said Rep. Tammy West, a Republican running for her third term. “It’s their tax dollars. This is not the government’s money. This is not an agency’s money.”

The legislative probe comes on top of an August federal audit that required “urgent attention” in over 30 different areas. And earlier this month, a grand jury found “pervasive mismanagement” in the handling of two pandemic relief programs for students, one of which Walters administered.

The grand jury report shows “he’s not competent or qualified to handle millions of dollars, let alone … $4 billion,” said GOP Rep. Mark McBride, referring to the size of the state education department’s annual budget. McBride, who oversees the department’s finances and is one of Walters’s more persistent critics, said he expects the upcoming legislative report, due Oct. 29, to show “further examples of the incompetence of the department of education under his leadership.”

Even some of those who have supported Walters are openly saying that the steady drumbeat of controversy is not only hurting schools, but Republican chances at the polls in November.

Kendal Sacchieri is a former high school Spanish teacher now running as a Republican for state Senate. Like West, she is anti-abortion and pro-parental rights. Such views would typically place her firmly in Walters’s camp. But she said she was “floored” by his recent budget request for $3 million to purchase Bibles for schools.

“If Ryan Walters is trying to get a point across that we need to be teaching more Christian values, then he needs to go about it a different way,” she said. “Ryan Walters is not doing Republicans any favors.”

‘Talent drain’

Critics say he’s been busy building a national brand, fueled by $60,000 in state funds he used to hire a publicist responsible for elevating his profile in conservative media. He is a frequent guest on Fox News and right-wing talk radio shows, where he’s opined on hot-button national issues seemingly far afield from running Oklahoma’s schools, like the war in Gaza and illegal immigration on the southern border. He traveled at taxpayer expense to Phoenix for a retreat with the conservative Heritage Foundation in March and in July attended the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee.

If his primary aim is self-promotion, he’s been “highly successful,” said Deven Carlson, a political science professor at the University of Oklahoma.

“Everywhere you look, you see him gaining media opportunities and speaking engagements that no other secretary of education in the country has ever gained,” Carlson said.

Walters has said he inherited a “dumpster fire” from predecessor Joy Hofmeister when he took office almost two years ago. But as students headed back to school in August, signs that the state’s school machinery was sputtering were hard to miss.

Services for many students with disabilities were disrupted for about a month when teachers and therapists couldn’t access a database with special education plans. The state also delayed $250,000 for emergency inhalers to combat asthma, a condition suffered by about 10% of Oklahoma students. The education department blamed a software update for the technical glitch, while confusion over how to write the contract for inhalers held up that purchase for a year.

When confronted, Walters frequently gets personal. That’s what happened in a spat over Title I funding, a perennial responsibility for state chiefs across the country. It’s a particular concern in Oklahoma, where 1 in 5 children live below the poverty line and districts rely on $225 million in federal funds for tutoring and afterschool programs. Districts typically get estimates in the spring, allowing them time to recruit and hire staff for the fall.

When late July came without a word, Rob Miller, superintendent of the Bixby, Oklahoma, schools, couldn’t suppress his frustration any longer. Venting on X, he attributed the delay to Walters falling down on the job amid a “talent drain” under his leadership. More than 130 employees — over a third of the staff — have left or been fired under his watch, according to local news reports.

At a press conference four days later, Walters called Miller “a clown and a liar” and pointed — without evidence —to “all kinds of financial problems” in his district.

The name-calling didn’t phase Miller, a former Marine major who participated in the 1991 operation to recapture the Kuwait airport from Iraqi forces during Operation Desert Storm. But the accusation of mismanagement rankled: The district had just received a clean audit.

“We’ve checked with his folks, and they don’t know what he’s talking about,” said Miller, who calls himself a Reagan Republican. “It was obviously a false claim, and he’s made no attempt to retract it.” In turning down a request for comment for this article, department spokesman Dan Isett cited Walters’s “very busy schedule.”

Responding to the controversy, a local business printed “I Stand with Rob” T-shirts, and former military members in the state House said in a statement that they couldn’t “stand by while a respected leader and veteran is insulted and demeaned for simply doing his job.”

Miller, meanwhile, has filed a defamation lawsuit, seeking at least $75,000 from Walters. The state ed chief has called the suit “frivolous,” adding that he should be immune from such litigation because he was acting in his official capacity.

‘Left-wing apparatus’

In an August interview with Blaze News Tonight, a conservative talk show, Walters made no apologies for promoting his priorities over maintaining a bureaucracy he says has turned schools into “state-sponsored atheist centers.” He said state employees who were fired or quit were part of a “left-wing apparatus” that has tried to undermine his agenda. He even plans to use savings from their departure to help defray the multimillion-dollar costs of his Bible initiative.

It’s talk that has some appeal in Oklahoma, where two-thirds of voters chose Donald Trump in 2020 and many sympathize with the former president’s rhetoric about the bureaucratic “deep state” and “swamp” in Washington.

And there are some lawmakers who haven’t lost faith in Walters’s ability to turn around an education system that consistently ranks among the worst in the nation. Rep. Chad Caldwell, a Republican from Enid, north of Oklahoma City, said career educators and the local media have treated Walters unfairly, accusing him, for example, of allowing political ambition to interfere with his job when Hofmeister spent over a year of her second term on a failed bid for governor.

He pointed to Walters’s announcement earlier this year that 117 schools across the state had made enough academic progress to be removed from a list of 191 low performers — news, he noted, that his own local paper didn’t even cover.

Walters first connected with Caldwell over text.

The lawmaker was sponsoring a bill to eliminate the statewide salary schedule for teachers and let districts set their own rates. The plan was highly unpopular with teacher groups, who argued they would lose automatic raises. But Walters, no fan of unions, reached out to show his support.

During pandemic lockdowns, Caldwell worried about his kids falling behind academically as they learned from home. His thoughts turned to Walters, previously a popular AP history teacher from the southeastern Oklahoma town of McAlester and a 2016 finalist for state Teacher of the Year. Caldwell convinced his twins, then in high school, to log in to one of the award-winning teacher’s virtual classes.

“My son, after one class, said, ‘Mr. Walters is the type of teacher that makes you want to go to school,’ ” Caldwell said. “I’m not a teacher, but I would think that’s about the best compliment that you could ever hope for.”

But even he said he is eager for the release of the House investigation to separate suspicions of wrongdoing from actual misconduct.

“I would have concerns if … he was intentionally thwarting the will of the legislature,” he said.

Caldwell was not among the 20-some House Republicans who signed a letter in August calling for an impeachment investigation into Walters. House Speaker Charles McCall rejected that idea, saying he would not “overturn the will of the people.” But he OK’d the probe into department finances.

To some, such conflicts are evidence that Walters is enmeshed in a “spiritual battle.”

“He’s doing the right thing, and sometimes the right thing gets you bad press,” said Jackson Lahmeyer, who leads Sheridan Church and founded Pastors for Trump. Lahmeyer, who calls pro-LGBTQ positions “demonic,” met Walters when he was running for superintendent in 2022. At a church service in June, he thanked Walters for his push to put Bibles in every public school classroom — a plan that’s now the subject of a lawsuit from parents, teachers and faith leaders.

“I know it feels like … the world is against you right now,” Lahmeyer told the superintendent as Walters’s three youngest children clung to his side. The pastor prayed while the congregation stretched their hands toward the altar.

In October, news emerged that suggested the narrative of Walters’s Bible push may not be completely inseparable from his political ambitions. Oklahoma Watch revealed that the only versions of the Bible that would fit Walters’s criteria were those endorsed by Trump and his son, potentially stifling competition from other vendors. The former president earns endorsement fees from the God Bless the USA Bible, which costs $59.99. He’s taken in $300,000 in sales, according to a recent campaign finance filing.

A week after the article was published, the department loosened the specifications to allow more companies to bid.

A department ‘in transition’

One member of the education department exodus under Walters was Matt Colwell, who served as director of school success until the superintendent fired him for exposing internal emails intended to clamp down on staff members talking to the media. He’s suing Walters and a top aide for wrongful termination.

To Colwell, episodes like the Title I blowup fit a familiar pattern. “His strength is threatening; his weakness is administration,” he said of Walters. “There were tons of comments like, ‘I’ve directed my staff to do A,B,C and D on curriculum.’ And then I’d talk to the curriculum people, and they’re like, ‘We haven’t heard a thing.’ ”

Staff turnover, he said, likely explains the sheer volume of findings in the recent federal audit. By the end of summer 2023, almost no one who had been overseeing federal grants was left. Staff that remained “didn’t know who to ask” when federal officials posed questions, Colwell said. “Each department would know their little slice of how that money was being spent, but nobody had the big picture.”

The departed include those who once celebrated Walters’s ascent. Pam Smith-Gordon, a veteran educator and conservative Christian, said she appreciated his focus on “the basics” and believed Oklahoma’s standing in national education rankings would improve under his watch. She was eager to join his administration and took a position in charge of monitoring grants in 2023.

But she quickly grew disillusioned. He wouldn’t meet with her, Smith-Gordon said, and she was locked out of computer programs she needed to do her job. She recalled waiting weeks, sometimes in vain, for his signature on grant applications. Smith-Gordon said her only glimpse of him before quitting four months later was when she looked out the window one morning and saw him walking to his car.

In a statement following her resignation, she described Walters as a “dictator” who publicly scolds and humiliates districts and said he spent more time “with cameras instead of in the halls of a struggling [department] in transition.”

‘Wear us down’

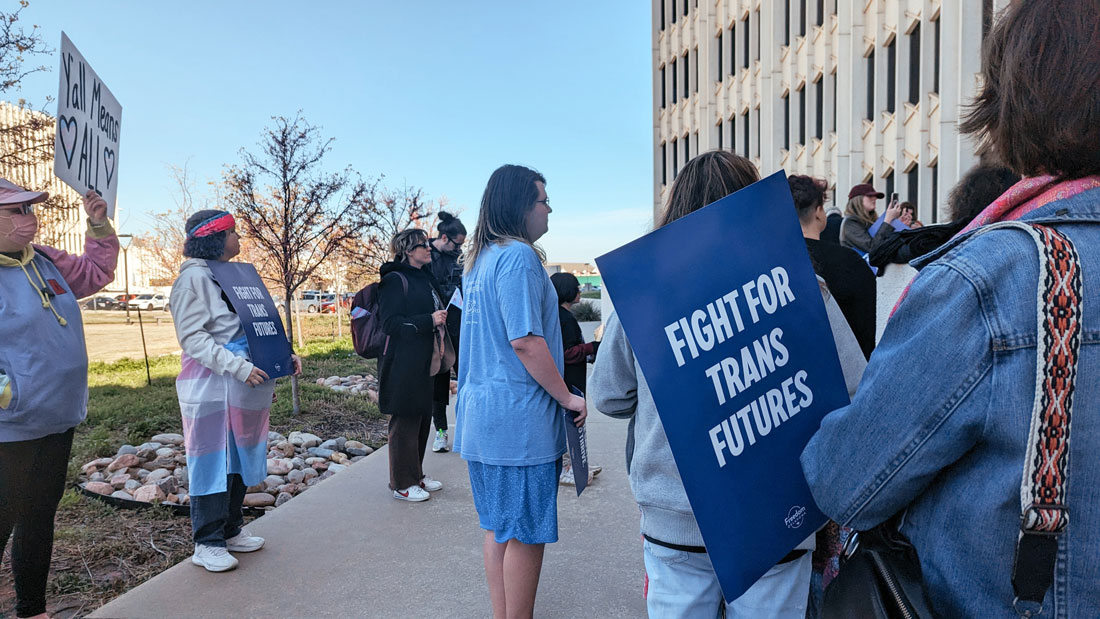

One of Walters’s frequent targets has been the LGBTQ community. A principal in the Western Heights district, for example, resigned under pressure after an anonymous letter revealed that he performed in drag on the weekends. Walters called repeatedly for his removal. Protesters drove in from across the state and stood outside school board meetings and the principal’s school with signs that read “Got AIDS yet?” and “Homo sex is sin.”

“It was terrifying for the kids,” said Nicole McAfee, executive director of Freedom Oklahoma, an LGBTQ advocacy group. “I think that teachers see that and worry that anything that might be perceived as supportive of queer kids could make them the next target.”

Some of his forays have run afoul of the courts. In June, the state Supreme Court accused him of operating with “unauthorized quasi-judicial authority” when he and his like-minded state board instituted rules against library materials with sexual content. He had tried to force the Edmond district to remove The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini and The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls from high school libraries. Some members of the community found the books too sexually explicit, but state law leaves those decisions up to districts.

Walters responded to the ruling with a familiar counterpunch, labeling Edmond “the face of pornography in schools.”

Such rhetoric has contributed to an environment of “fear” and “exhaustion,” said Leslie Briggs, legal director at the Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice. She represents a transgender student suing Walters over his rule preventing districts from changing a student’s sex or gender in student records without the state board’s OK.

Until recently, most district leaders were cautious about publicly criticizing Walters, and in Facebook groups, teachers warn each other to keep their social media accounts private.

“Obviously,” Briggs said, “it’s to his benefit if he can wear us down or wear the community down.”

‘A tough position’

No one has felt Walters’s wrath more than the Tulsa Public Schools, the state’s largest district, with 33,500 students. He demanded that Tulsa “stop emphasizing woke policies” like diversity training. And he pushed for former Superintendent Deborah Gist to step down, which she ultimately did in an effort to preserve the district’s accreditation and avert a state takeover.

For a year, he required Tulsa’s new leaders to drive the hour and a half to Oklahoma City to give monthly updates on their progress in academics, teacher training and financial management. So when he visited Tulsa’s Will Rogers High School in April, with only a couple days’ notice, and asked to teach a lesson, district leaders were apprehensive.

“It’s a tough position,” said Stacey Woolley, Tulsa’s school board president. “But we live in a place where making him angry certainly feels as though our students will potentially suffer.”

She watched him walk into an AP World History class that day and comfortably slip into his former role as teacher. In under 11 minutes, Walters packed in an analysis of political cartoons and seamlessly wove together perspectives on imperialism from Rudyard Kipling, Theodore Roosevelt and Thomas Jefferson. Surrounded by students sitting three or four to a table, he urged them to play the game Risk to better understand world domination and explained why America’s founders took a different path.

Every other country was “trying to be big and powerful and take over other countries,” he said, according to a recording of the lecture provided to The 74. “But America had this Declaration of Independence, so we’re going to protect people’s rights.”

It was a strange moment. Being in Walters’s crosshairs, Woolley said, has been stressful for staff and families. But she couldn’t deny his expertise.

“He is a teacher, a very good one,” she said. “I sat there in a state of cognitive dissonance.”

That day, Walters showed a side of himself that few have seen since he entered politics. It was the same enthusiasm for teaching that first impressed Rep. McBride when he met him six years ago. A home builder, McBride was new to education policy in 2018 when House Speaker McCall appointed him to chair the appropriations subcommittee on education. He wanted to better understand teachers’ concerns, so he reached out to Walters after catching him on the radio.

“Walters was such a breath of fresh air,” the lawmaker from Moore, south of Oklahoma City, told The 74. “He was just happy to be a teacher.”

Now, they regularly spar in the media, with Walters counting McBride among the “liberal Republicans” who “want pornography in your kids’ schools” and McBride saying it’s his responsibility to search for “waste, fraud and abuse.” Those nightly soundbites, however, don’t reflect their complicated relationship.

“We don’t hate one another,” said McBride, who will leave the House in November after serving the maximum six terms. During an exchange earlier this summer, he said Walters asked when they were getting together for biscuits and gravy. He agrees with some of the superintendent’s positions, like having fewer strings tied to federal funds. But as a “practical” Republican charged with monitoring the department’s fiscal affairs, he said he’s grown weary of Walters’s “political theater.”

“You can’t have that kind of ego and not eventually get caught up in your own self-worth,” he said. “You know it says in the Bible, ‘Pride comes before the fall.’ ”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter