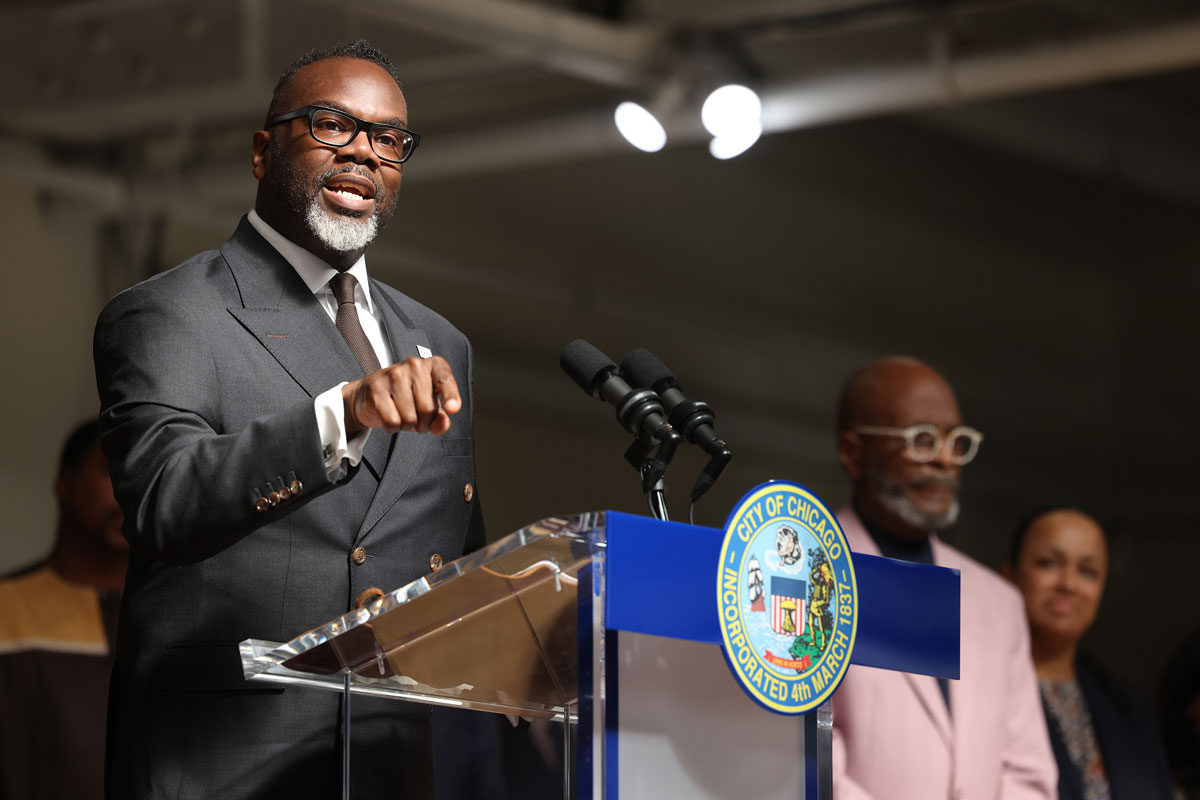

One of the most trying hours of Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s 17 months in office came on the morning of October 7, during a hastily arranged press conference to address the multiplying crises that threaten to engulf his city’s schools.

Johnson stood at the podium of the South Side’s Sweet Holy Spirit Church as he took questions about the abrupt resignation, just a few days prior, of all seven of his appointees to the local board of education. Flanked by a roster of supporters and aides, he introduced his choices to fill the departed members’ seats and once again pledged to bring progressive change to the fourth-largest school system in the United States.

It was a theme he’d sounded since his campaign kickoff speech nearly two years earlier, and one that helped transform him from a former educator and organizer for the Chicago Teachers Union into one of the most closely-watched young Democratic leaders in the country. For his allies, particularly the political powerhouse CTU, the consistency of the mayor’s messaging signaled his commitment to find more resources for Chicago Public Schools, even in the face of a yawning budget deficit and vanishing pandemic relief funds.

But if the event was intended to calm the uproar that has swirled around the district’s leadership and finances since the beginning of the school year, it was destined to fall short. From its outset, the mayor was interrupted repeatedly by a group of hecklers protesting the replacement nominees. After some were removed, Johnson grew testy with reporters, objecting several times that their questions were “disrespectful.”

In his most memorable complaint, the mayor dismissed critics who have rejected his spending plans — including a proposal for the district to take out a $300 million loan to fund teacher pay increases and pension contributions — by comparing their arguments to those of Confederate leaders during the Civil War.

Yet the number of those blocking his way has only grown in the last few months. They now include the district’s CEO, Pedro Martinez, who rejected the idea of a short-term loan over the summer; the seven departed board members, who gave up their titles after Johnson reportedly pushed them to fire Martinez; and no fewer than 41 of Chicago’s 50 aldermen, who signed an open letter sternly counseling against further borrowing and voicing concern about the sudden empowerment of “lame-duck appointees” over the remainder of the board’s term. Public opinion is no sunnier, with a poll released last month revealing that 60 percent of Johnson’s constituents disapprove of his leadership.

At the heart of the conflict rests an elemental question: Who will govern Chicago’s schools? Mayors have enjoyed the right to appoint and dismiss members of the school board for nearly three decades, and Johnson’s slate of replacements will be able to approve his agenda once they are seated. But the Illinois legislature recently swept aside mayoral control over the district, charging the city with establishing a popularly elected, 21-seat board by 2027. In November, voters will choose the first 10 elected members, with Johnson appointing 11, to a hybrid body that will preside over the transition.

The district will spend that interregnum attempting to balance its accounts, while also negotiating new contracts for teachers and principals and deciding the fate of scores of under-enrolled schools. Local K–12 leaders foresee increasingly bitter disputes arising over the reach of the CTU, which now appears to hold most of the leverage over critical decisions. At the same time, their opponents increasingly question the legitimacy of a process that has seen one iteration of the school board precipitously leave office, and another be appointed in its place, just weeks before the election of a third set of candidates.

Neither the mayor’s office nor the CTU responded to requests for comment from The 74.

Arne Duncan, who served as Chicago Public Schools CEO from 2001 to 2009 and, later, as the U.S. secretary of education, said he hoped both sides could compromise around the most pressing dilemmas facing students and educators. Now helping to lead a nonprofit devoted to the reduction of gun violence in dangerous neighborhoods, he observed that the tension around K–12 education could benefit from the type of de-escalation he often sees practiced between feuding gangs.

“Guys who have shot at each other still find ways to put that aside and make peace for themselves and their kids,” Duncan said. “If they can do that every day, I hope our elected leaders can find the courage to, metaphorically, put down the gun and do the right thing.”

But Meredith Paige, the mother of two high schoolers and a leader of the advocacy group CPS Family Dyslexia Collaborative, said that to everyday Chicagoans, the feeling was one of “chaos.”

“We might not see the impact on children for a couple of years, but on the ground, parents are saying, ‘What the [hell] is happening? The schools are falling apart, get me out of here.’”

‘A crisis of leadership’

Families have an immediate opportunity to make their feelings known in November, when Chicago will hold its first-ever school board elections.

The power to appoint members, who wield authority over the major policy choices in a district serving more than 320,000 students, has rested solely with the mayor since 1995. Throughout 2019, long-serving Mayors Richard M. Daley and Rahm Emanuel happily used that prerogative to overhaul the school system, lifting academic standards and opening over 150 new schools. Academic achievement flourished in the aftermath, with one nationwide analysis showing that students in Chicago Public Schools made more academic progress than those in virtually any other district in the United States.

But the public came to sour on the fast pace of change, especially after Emanuel successfully pushed for the closure of 49 schools in 2013. Public polling, along with a series of nonbinding ballot questions held throughout the city, showed that substantial majorities favored direct elections over the political appointment process. The Illinois legislature acknowledged that reality in 2021 by passing legislation to establish an elected board.

Dozens of candidates have filed to run for seats in the city’s 10 newly created school board districts, with many grouping into two blocs: one backed largely by the Chicago Teachers Union and left-leaning community groups, the other favored by donors inclined toward education reform, including charter school supporters. Campaign donations across the 10 races are already nearing $2.5 million, with charter-friendly groups reportedly accounting for the bulk of spending thus far.

Against that messy backdrop, Mayor Johnson has chosen six new potential board members, who are expected to be seated later this month, to preside over the district until newly elected members take office in January. In the new year, they may be either re-appointed or again replaced by a new group of Johnson appointees.

But in the meantime, they will be left with the critical decisions of whether to terminate the contract of CEO Martinez, who has served since 2021, and approve the mayor’s push to borrow hundreds of millions of dollars to defray short-term expenses, including a $175 million pension payment for non-teaching employees of Chicago Public Schools.

To cut staffing in a time when these kids just survived a pandemic? I don't think teachers and social workers and librarians are where we should focus our energy.

Byron Sigcho-Lopez, Chicago alderman

Byron Sigcho-Lopez, one of the nine alderman who did not sign the open letter criticizing the previous board’s mass resignation, said he was untroubled by the move, noting that the school board’s current term has nearly expired and that its members had not chosen to run for any of the elected seats.

“I don’t see any problem with the board leaving,” Sigcho-Lopez said. “This board had one more session left. I think they’re doing the responsible thing, and I thank them for their service.”

But most other local office holders have objected strenuously both to the substance of Johnson’s plans and the lurching shifts in CPS governance. Democratic State Rep. Ann Williams — who spearheaded the legislation that established a two-year interval of hybrid governance — said she was disturbed by the board’s unplanned turnover just weeks before Election Day. She added that she had been “inundated” with calls from worried constituents in her North Side district about what it might mean.

“This really flies in the face of what I was trying to do as sponsor of this bill in Springfield, which was to bring democracy to Chicago Public Schools,” Williams said. “What’s happened is a crisis of CPS leadership, and that’s how it’s being perceived by Chicagoans.”

Daniel Anello is the CEO of Kids First Chicago, a nonprofit that receives support from Chicago’s business and philanthropic communities and advocates for more parental voice in education policy. He argued that the developments of the last few weeks more closely resembled Emanuel’s “top-down” management style than the participatory democracy that voters hoped for in 2021.

“They’re just saying, ‘Here’s the replacement board’ and claiming that it was a smooth transition going as intended,” Anello said. “But then, why wasn’t the former board at the press conference? They just disappeared. It’s just not the inclusive promise of community engagement that this mayor ran on.”

Showdown over pensions, debt

The district projects that it will face a deficit of $505 million in the coming school year, stemming from a combination of normal operating expenses, increasing healthcare costs, and the expiration of federal ESSER funds that helped states weather pandemic-related shortfalls in revenue. The long-term picture has been further clouded by steadily decreasing student enrollment, which has dropped by more than 80,000 students — or roughly one-fifth — since 2010.

The administration of former Mayor Lori Lightfoot, Johnson’s immediate predecessor, also transferred hundreds of millions of dollars in pension costs to CPS that had historically been underwritten by City Hall — a reflection, they argued, of the district’s new independence from mayoral control, which Lightfoot had opposed in 2021. While Martinez traveled to Springfield in May alongside CTU leaders to ask lawmakers for additional funding, the resulting increase wasn’t close to what had been requested.

A source close to the district, who asked not to be named in order to speak freely about political matters, said the unsuccessful pitch to Gov. J.B. Pritzker and other Illinois Democrats served as a wake-up call that the district would not be spared from retrenchment in the coming years.

“I think that the union thought, once Brandon got elected, that they’d be able to walk into Springfield and get whatever they wanted,” the source said. “But there’s no money, especially after ESSER funds have expired.”

In July, Martinez and the school board put forward a $9.9 billion budget proposal that aimed to close the deficit through a mixture of staff cuts and freezes to almost 250 jobs. In an unusual response, the mayor harshly criticized the fiscal direction laid out by his own hand-picked board, counter-offering that the district borrow $300 million to cover its costs. Instead, the budget was authorized as written.

After that, the source remarked, the relationship between the mayor and district leadership “went south very quickly.” The CTU, which had already joined Johnson’s attack on the proposed cuts, accused Martinez of planning to close more schools. By mid-August, the mayor was widely thought to be preparing to fire his schools chief.

In a statement, Martinez expressed optimism that some breathing room might be gained by using surplus dollars from the city’s special “tax increment financing” districts, which are funds designed to attract developers and employers. Using those resources, he argued, “we can address these looming costs without cuts, without taking on expensive short-term debt, and without waiting for additional funding to materialize from the state.”

But even if both sides can agree on a new source of spending, the district and the union are simultaneously engaged in a contentious negotiation over the terms of the next teacher contract. The Civic Federation, a non-partisan research group, has estimated that once the district pays out an expected series of teacher raises and assumes more pension debt from the city, its deficit will approach $1 billion.

Karin Norington-Reaves is a candidate for the elected seat in the city’s 10th school board district. A critic of Mayor Johnson, she has pledged not to accept donations from the CTU. She warned that if Johnson’s newly appointed board resorted to accepting a “payday loan,” it would only bring more financing costs and could lead to the district’s bonds being downgraded.

“Anybody with any level of financial acumen understands that when you have debt, and you borrow, you create further debt,” Norington-Reaves said. “If you were an individual, that would tank your credit worthiness, and it’s no different for the school district.”

I don't want to have to leave my city, but I will, if that's what I have to do for my child. I am tired of fighting what feels like an uphill battle.

Karin Norington-Reaves, candidate for Chicago school board

But Sigcho-Lopez, the alderman, countered that Chicago students’ learning needs were too great to countenance staffing reductions, especially given the still-significant trauma of COVID.

“To cut staffing in a time when these kids just survived a pandemic? We’ve got kids who are orphans, who need extra social workers,” he said. “I don’t think teachers and social workers and librarians are where we should focus our energy.”

Tough decisions ahead for new board

The priorities of Johnson’s newly selected board members remain unclear for now. Any action taken against Martinez is likely to prove explosive to politicians and educators alike; in August, when his termination was first rumored, over 400 CPS principals and assistant principals signed a letter opposing the idea.

Though Johnson retains the power to appoint more than half of the incoming members of the hybrid board, November’s election outcomes will also help determine the course taken over much of the remainder of his first term. If the CTU’s preferred candidates prevail in their contests, they will likely take it as an endorsement of the positions shared by both the union and the mayor.

The expense and pugnacity of the campaigns have already proven discouraging to some who had welcomed the arrival of an elected board. Parent Meredith Paige said that a friend and fellow activist had explored a run, but she was quickly discouraged by the demands of the process — the number of signatures required to run was raised from a proposed 250 to 1,000, more than twice that required to run for the Chicago City Council — and abandoned the notion.

“It just came out how much the charter schools are pouring into these races, and how much CTU has spent,” she lamented. “It’s exactly how people worried it was going to go.”

Norington-Reaves, a longtime nonprofit director and former congressional candidate, sounded confident in her ability to win the support of voters but argued that the stakes for the election seem higher than they should be. A Chicago native, she said she and others had long resisted the temptation to decamp to higher-performing suburban districts, but that her daughter’s learning needs were ill-served in her hometown.

“I don’t want to have to leave my city, but I will, if that’s what I have to do for my child.” Norington-Reaves concluded. “I am tired of fighting what feels like an uphill battle for investment, for economic development, and for good education just to have it be undermined. It feels like [the mayor] is willing to give it all to CTU.”

Duncan, a former high-level college basketball player, drew a comparison between the district’s situation and that of the Michael Jordan-era Chicago Bulls. In the end, he said, that team dissolved not due to failures on the court, but rather to personality conflicts among the franchise’s leadership and players.

Like the Bulls, Duncan said, Chicago Public Schools had a record to be proud of — and protected.

“No one beat the Bulls, they just imploded because they didn’t realize that the whole was bigger than the sum of their parts. Twenty-five years later, Chicago’s never had a championship basketball team. You don’t recover from these kinds of things.”

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation and the Joyce Foundation provide financial support to Kids First Chicago and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter