4 St. Louis Schools Getting $1M in Grants to Rethink How They Teach Kids to Read

Emerson Challenge awarding 20K this year, 250K in 2025-26 to help educators collaborate on best ways to implement science of reading, boost literacy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Four St. Louis schools will be revamping their approach to reading instruction in a new two-year program created to boost literacy for K-3 students.

In September, St. Louis education nonprofit The Opportunity Trust launched the Emerson Early Literacy Challenge, a $1 million effort to help charter and district schools brainstorm ways to improve reading in the early grades. The four schools, selected from St. Louis City and County are Atlas Public School, Commons Lane Primary School in the Ferguson-Florissant School District, Premier Charter School and Barbara C. Jordan Elementary in the School District of University City.

The Emerson challenge is a direct response to work the St. Louis NAACP is doing to improve reading scores and close the literacy gap for Black students, said Jesse Dixon, an Opportunity Trust consultant and one of the project leaders for the challenge. The project is being funded by a $1 million donation from Emerson, an international automation technology and software company headquartered in St. Louis.

The NAACP branch recently filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights against 34 St. Louis school districts because of disparities in reading proficiency for students of color.

The branch also launched a campaign this year called Right to Read, which is working with superintendents, teachers, parents and nonprofits to get all third graders in the city and county of St. Louis reading well by 2030. Dixon said the Emerson challenge is building on the campaign’s principle that requiring instruction based on longstanding research about how children learn to read — the science of reading — is key to improving literacy.

“For years, teachers had been trained how to teach reading in ways that we’ve now since learned are counterproductive and actually hinder the progress of kids learning to read,” he said. “It … sent a strong message about how big a problem this was and how evident it’s become that we need to teach reading in this other way.”

Dixon said a big problem in improving St. Louis’s reading proficiency rates — which were at 18% for third graders in the city and 43% for third graders across the county in 2022 — is how the science of reading is implemented.

“Many districts and charter schools have already adopted science of reading curriculum, and yet, we’re still not getting much better,” Dixon said. “These are well-intentioned, hardworking, smart educators and education leaders doing everything they can to try to catch these kids up and get them to be proficient, and something’s not working, and we need to learn what it is.”

Leaders of each selected school will receive $20,000 this year to brainstorm strategies and craft plans to improve early literacy. They can get up to $250,000 during the 2025-26 school year to implement those plans. The Opportunity Trust will also provide support from literacy experts.

Dixon said the school leaders will have to look outside St. Louis, to districts that have successfully implemented the science of reading and boosted literacy.

“They can learn what’s working around the country and they can learn from each other,” he said. “At the end, [they will] write a plan for how to spend their quarter of a million dollars consistent with everything they’ve learned, and so that they can implement those practices next school year and get the kind of results we all know are possible.”

Dixon said St. Louis education officials and experts still don’t know what’s going wrong with schools that have adopted science of reading curriculum but seen no results.

“That’s part of the challenge — we don’t think any school in St. Louis has figured this out,” he said.

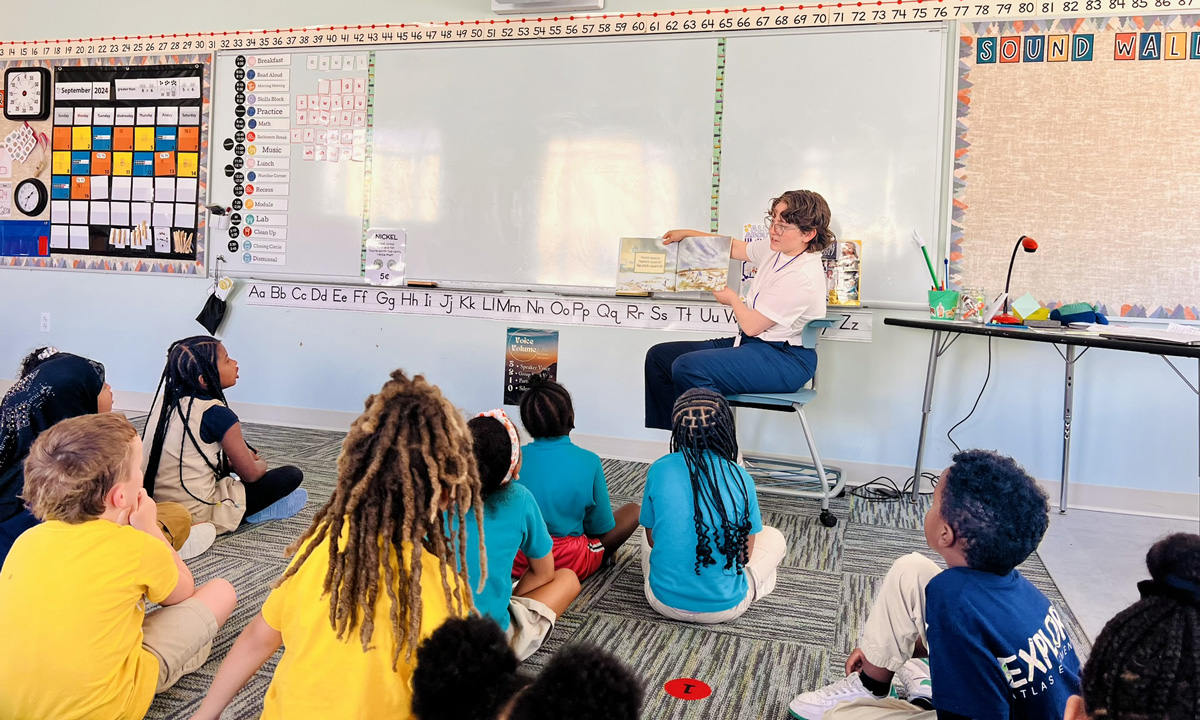

One of the selected schools, Atlas Public School, incorporated curriculum materials based on the science of reading when it opened in 2021. The school serves more than 460 students from prekindergarten through fourth grade.

Colby Heckendorn, executive director and co-founder, said Atlas students scored slightly above average this spring, ranking in the 51st percentile for reading on the NWEA MAP Growth assessment — a test that’s widely used in schools across the U.S.

“We feel good about that, but we still know and believe our students can do better,” Heckendorn said. “That’s why it’s important for us to continue to refine our practice and make sure that our teachers feel supported and have the training that they need.”

Heckendorn said he’s looking forward to collaborating with other schools to brainstorm strategies around reading instruction.

“I think that’s one of the things that’s going to be great about the literacy challenge — really reflecting on how we are best supporting our students who need more enrichment and to be pushed to the next level,” he said. “How are we supporting those students who are really struggling, to set them up for success as well? Those are things that our team is really excited to dig into and reflect on.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)