As Feds Invest in New Bilingual Teachers, State Licensing Hurdles Must Go

States should target more diverse alternative teacher training programs, remove English-only licensure exams and elevate existing bilingual staff.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

For much of the past few years, most of the oxygen in public education has been consumed by fiery culture wars: banning books, erasing Black history from textbooks and school campuses, and even threats to challenge the Supreme Court’s 1982 decision that required public school systems to educate all children regardless of immigration status.

This wave of backlash, forced by America’s culturally anxious fretting over whether “their” country is changing too fast for their liking, is nothing new. In fact, the anti-immigrant, anti-Black pendulum swing in the United States, usually after periods of progress, is about as predictable as it gets.

Fortunately, there’s ample evidence that this — the ugly, illiberal drama — too may pass. The United States continues to grow more racially, ethnically, linguistically and culturally diverse, and this panoply of human riches is showing up in our schools. This is particularly clear when it comes to languages on campus — there are over a million more English learners in U.S. schools than there were in 2000, and states have been steadily reversing their mandates banning bilingual education.

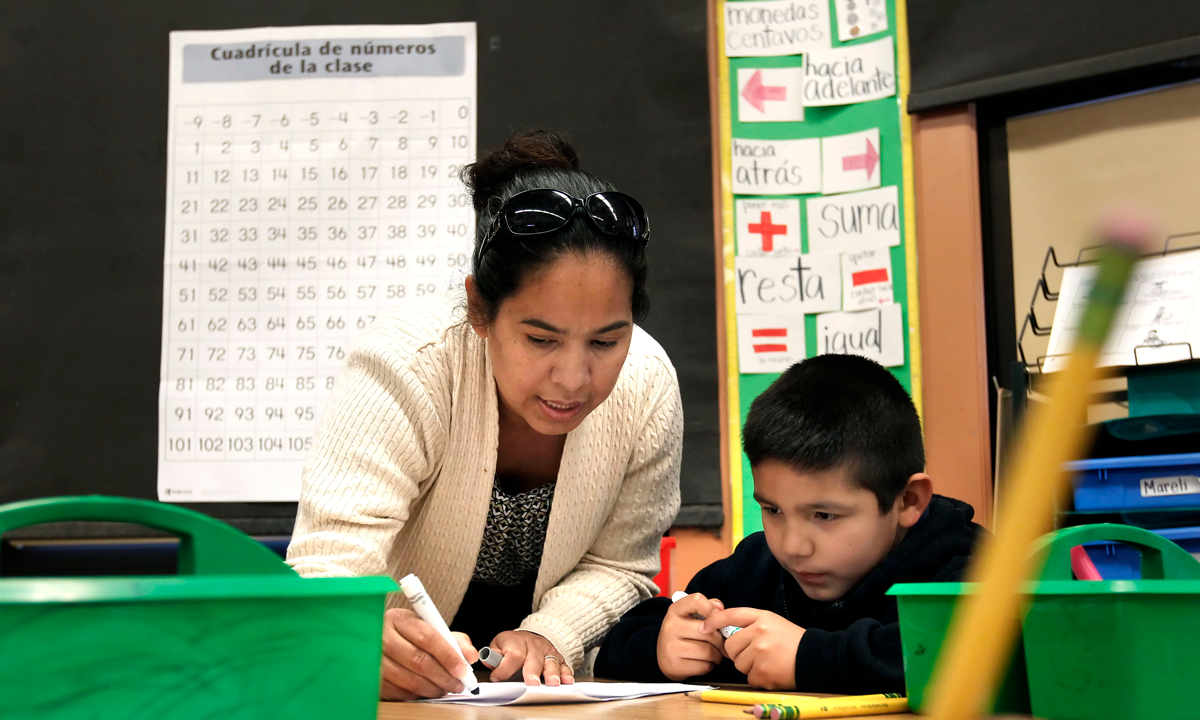

Dual language classrooms offering academic instruction in two languages (and often integrating English learners and English-dominant children) are immensely popular across the country. This is the real story of American public schools today — plural, polyglot campuses adjusting their pedagogies to meet the needs of a wide range of learners.

And yet, it’s no simple matter to make those adjustments. While talk of national teacher shortages appears to be premature, demand for bilingual teachers has long outstripped supply. American teachers are disproportionately white and monolingual — a major stumbling block for schools hoping to offer more bilingual learning opportunities. The country can’t have more bilingual schools, let alone dual language programs, unless it trains, hires and retains more teachers who can work proficiently in languages other than English.

Policymakers are working on the problem. The U.S. Department of Education recently announced over $18 million in Augustus F. Hawkins Centers of Excellence Program grants to support the training of more racially, ethnically and linguistically diverse teachers. The dozen grantees chosen in this round of the competition encompass a large number of institutions prioritizing teacher diversity that includes language considerations. Florida International University is using its $1.5 million grant to train, certify and place more than 100 bilingual teachers. Importantly, its program will include cohorts of Spanish-English bilingual teacher candidates and Haitian Creole-English bilingual teacher candidates. The University of Texas-El Paso is using its grant to recruit Latino teachers to work in bilingual settings.

These investments will help expand access to bilingual education around the country, a goal with myriad benefits drawn from multiple fields of research. First, a raft of studies show that English learners do best in schools that support their emerging bilingualism. Dual language is the most effective model for helping English learners maintain their bilingualism, reach English proficiency, and succeed academically. It also appears to support more diverse school enrollment.

Further, studies suggest that students gain academically from having teachers who match their racial or ethnic identities. Dual language programs may produce unique benefits in this regard if members of their linguistically and culturally diverse teaching staff resemble the identities of their students. And indeed, a large majority of dual language schools offer instruction in Spanish and English — and regularly rely upon large numbers of Spanish-dominant Latino teachers. Most English learners are Latinos and native Spanish speakers.

Finally, research indicates that bilingual individuals often garner unique individual strengths, like an improved ability to focus and empathize. And that’s to say nothing of the collective economic and diplomatic advantages the country gains from fostering a polyglot society.

But all of this research — and correspondingly high family demand for bilingual instruction in communities around the country — won’t lead to expansions of bilingual and dual-language schooling on their own. As one of us outlined in a Century Foundation report a little over a year ago, many state training and licensure systems remain largely hostile to multilingual teacher candidates, existing dual language schools are sometimes established to provide bilingual instruction to English-dominant children — even as English learners are consigned to English-only instruction, and so forth.

So there’s more for policymakers to do. Federal and state leaders should consider prioritizing investments in teacher training programs with a track record of producing high-quality bilingual teachers. This must include alternative teacher training programs, which tend to be significantly more diverse than traditional programs. Indeed, in March, the Biden administration proposed doubling the country’s investment in the Augustus F. Hawkins grants from $15 million to $30 million.

And state policymakers should consider updating their teacher licensure systems to remove chokepoints — like English-only licensure exams — that prevent linguistically diverse teacher candidates from reaching the classroom. States should also optimize the linguistically diverse staff already serving in their classrooms — many of whom are aides or paraprofessionals — and fund pathways to help them become lead teachers.

Or, you know, they could ignore the challenge of growing our bilingual teacher corps — an opportunity sparked by genuine progress and improvement in American schools — and focus their energies on demagoguing over the book selection in elementary school libraries. This really shouldn’t be a tough choice.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)