Providence Students’ Sensitive Data Exposed in Cyberattack — District Denies Leak

Rhode Island’s largest school district alerted current and ex-employees affected by massive data breach but has yet to acknowledge student victims.

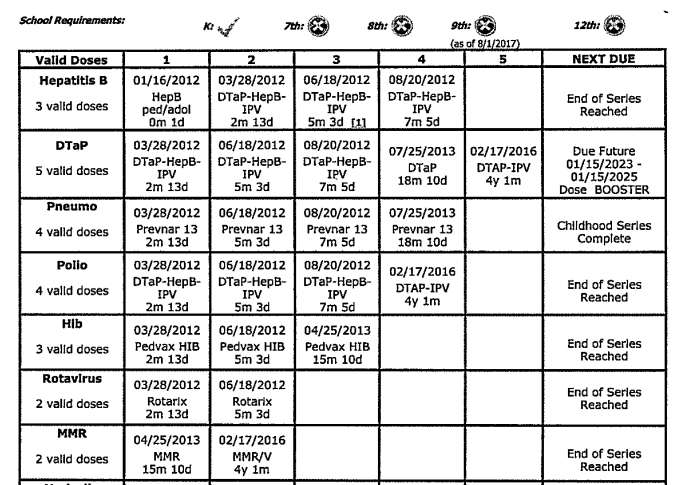

Sexual misconduct allegations involving both students and teachers, children’s special education records and their vaccine histories are readily available online after the Providence, Rhode Island, school district fell victim to a cyberattack last month.

A ransomware gang uploaded those and other sensitive student information to an instant messaging service after Providence Public Schools did not pay their $1 million extortion demand, an investigation by The 74 revealed. Though the files have been available online for nearly a month, parents and students are likely unaware that their private affairs have entered the public domain — and district officials have denied the leaked records exist.

Earlier this month, the school district notified 12,000 current and former employees that personal information, such as their names, addresses and Social Security numbers, had been compromised and offered them five years of credit-monitoring services. But the letter never made mention of students’ sensitive records and, district spokesperson Jay Wégimont told reporters at the time that an ongoing investigation had uncovered “no evidence that any personal information for students has been impacted.”

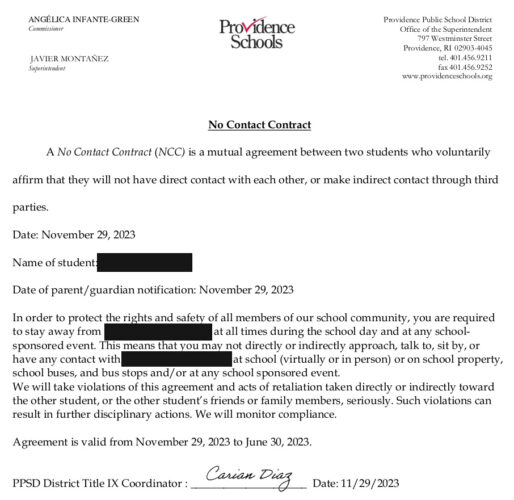

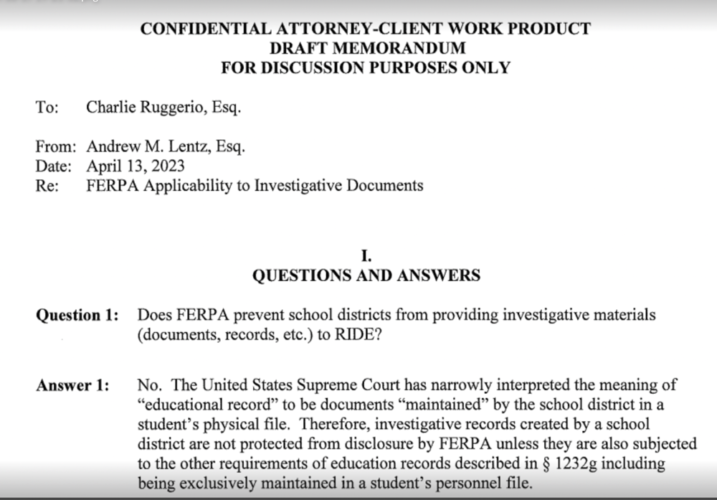

An analysis by The 74 of the stolen files — posted by the threat actors to the messaging platform Telegram — indicates otherwise. Included in the 217 gigabyte data leak are students’ specific special education accommodations and medications. Other files offer detailed insight into district investigations into sexual misconduct allegations naming both educators and students.

In one complaint, a middle school girl accused a male classmate of showing her unsolicited sexual videos on his cellphone, lifting up her skirt, snapping her bra strap and pulling her hair. In another, a mother accused two high school boys of putting their hands into her disabled daughter’s underwear. After one incident, a boy uttered a threat: “Don’t tell nobody.”

In a statement to The 74 on Wednesday, Wégimont said the district has “been able to confirm that some files” stored on the district’s internal servers were accessed by an “unauthorized, third party,” and that “security consultants are going through a comprehensive review” to determine whether the leaked files contain personal information “for individuals beyond current and former staff members.”

Wégimont’s statement doesn’t acknowledge that students’ records had been compromised.

The district’s failure to acknowledge the breach affected students and parents — even after being informed otherwise — is “a massive violation of trust with communities,” student privacy expert Amelia Vance told The 74.

“People should be aware — especially when particularly sensitive information is being released in ways that could make it findable and searchable later,” said Vance, the founder and president of Public Interest Privacy Consulting. As cybercriminals turn their focus beyond financial records to sensitive information like sexual misconduct allegations, breaches like the one in Providence “are likely to have a substantial impact on people’s future lives, whether it be their opportunities, their ability to get a job or their relationships with others.”

The school district acknowledged in an Oct. 4 letter to the state attorney general’s office — and in letters to the individuals themselves — that the sensitive information of 12,000 current and former employees was “potentially impacted” in the attack. A spokesperson for the AG’s office shared the letter that Providence Superintendent Javier Montañez submitted “as required by statute,” but declined to comment further on the students and families who were also victimized in the breach.

Under the state’s data breach notification law, schools and other municipal agencies are required to notify affected individuals within 30 days — but only after an investigation determines the breach “poses a significant risk of identity theft.” Covered records include individuals’ names, Social Security numbers, driver’s license numbers, financial information, medical records, health insurance information and email log-in credentials.

It’s unclear how the district determined as many as 12,000 current and former educators were affected. Nobody, including the school district, was previously able to access the breached records, Victor Morente, the state education department’s spokesperson, said in a phone call on Wednesday.

“No one had actually gone in to see the files,” he told The 74, although the district had said it was conducting an ongoing analysis.

The state took control of the 20,000-student Providence district in 2019 after a report found it was among the lowest performing in the country. State education officials are “working closely with the district” on its ransomware recovery, Morente said.

Thousands of students impacted

Included in the leak is the 2024-25 Individualized Education Program for a 4-year-old boy who pre-K educators observed had “significant difficulty sustaining attention to task” and who “wandered around the classroom setting without purpose.” Another special education plan notes a 3-year-old boy “randomly roamed the room humming the tune to ‘Wheels on the Bus,’ pushed chairs and threw objects.”

A single spreadsheet lists the names of some 20,000 students and demographic information including their disability status, home addresses, contact information and parents’ names. Another includes information about their race and the languages spoken at home.

A “termination list” included in the breach notes the names of more than 600 district employees who were let go between 2002 and 2024, including an art teacher who “retired in lieu” of being fired and a middle school English teacher who “resigned per agreement.” Another set of documents revealed a fifth-grade teacher’s request — and denial — for workplace accommodations for obsessive compulsive disorder, anxiety and panic attacks that make her “less effective as an educator if I am not supported with the accommodations because I can not sleep at night.”

In one leaked April 2024 email, a senior central office administrator sought a concealed handgun permit from the state attorney general, noting they “have a safe at work as well as one at home.”

Threat actors with the ransomware gang Medusa, believed by cybersecurity researchers to be Russian, took credit for the September attack. The group, which has repeatedly used highly personal student records as part of its extortion scheme, posted Providence public schools to its dark web blog where it demanded $1 million.

While ransomware gangs have long restricted their activities to the dark web, Medusa is “fearless and flashy,” according to the cybersecurity company Bitdefender. After Medusa outs its latest target on its dark web “name and shame blog,” it then previews the victim’s stolen records in a video on a faux technology blog that appears to be directly tied to the attackers.

The files are then made available for download on Telegram. While the dark web requires special tools and some know-how to access, the preview video and download link to the Providence files and those of other Medusa victims are available with little more than a Google search.

Medusa’s many tentacles

The Medusa attack and Providence’s response is similar to those of other school districts in the last two years. After Medusa claimed a 2023 ransomware attack on the Minneapolis school district — what officials there vaguely called an “encryption event” — the threat actors leaked an extensive archive of stolen files, including school-by-school security plans and documents outlining campus rape cases, child abuse inquiries, student mental health crises and suspension reports.

In St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, school officials waited five months to notify people their information was stolen in a July 2023 Medusa cyberattack — and only after a joint investigation by The 74 and The Acadiana Advocate prompted an inquiry from the Louisiana Attorney General’s Office.

The Providence district records available on Telegram are extensive, totaling more than 337,000 individual files and 217 gigabytes of data. Even the 24-minute video preview exposes an extensive amount of personally identifiable information. Though the group focuses on the theft of sensitive records — like those pertaining to student civil rights investigations, security plans and financial records — a tally of the total number of affected Providence district data breach victims is unknown.

Personally identifiable information is intertwined with more mundane documents housed on the breached school district server, including veterinarian bills for a high school teacher’s German Shepherd named Sheba and a recipe for pulled BBQ chicken sliders with pineapple coleslaw.

Indicators of a cyberattack on the Providence district first appeared in September when the school system was forced to go several days without internet due to what officials called “irregular activity” on its computer network but declined to comment on whether they’d been the target of ransomware. In a Sept. 25 letter two weeks later — and the same day that Medusa’s ransom deadline expired — Superintendent Montañez acknowledged that “an unverified, anonymous group” had gained “unauthorized access” to its computer network and claimed to have stolen sensitive records.

“While we cannot confirm the authenticity of these files and verify their claims,” Montañez wrote, “there could be concerns that these alleged documents could contain personal information.”

Three days later, on Sept. 28, hundreds of thousands of files became available for download on Telegram.

This story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)