With $8.5M Investment, New Mexico Tries Once Again to Get Tutoring Right

The state, ranked last in 4th grade testing, hopes to succeed after recent federally funded efforts reached just a fraction of students.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In April, New Mexico launched a tutoring effort with all the “high-impact” elements experts say lead to success: small groups, led by a trained tutor for 90 minutes of instruction spread throughout the week.

It was the third attempt in two years.

With the school year winding down, some districts never even got word the program existed. Those that participated quickly scrambled to cram it into their schedules.

“The timing wasn’t optimal,” said Matt Montaño, superintendent of the Bernalillo Public Schools, north of Albuquerque, and one of just five districts out of the state’s 89 to sign up. Staff members, he said, were “a little bit less than enthusiastic” about the interruption.

The late rollout was only the most recent snag in the state’s troubled effort to spend millions in federal relief funds for tutoring before the deadline to use the money hits next month.

The first attempt — with an on-demand, virtual provider — met with a meager response from families. A second try never got off the ground because of a contract mishap the state still won’t fully explain. And the delayed start on the third effort means only a fraction of the students slated for tutoring got it. State officials estimate that between 2,000 and 3,000 students received the extra help — far less than the 8,000 they were hoping to reach.

“Clearly, it was not the best,” Amanda DeBell, New Mexico’s deputy education secretary, said of the condensed program. But in July, the legislature pumped new life into the effort, providing $8.5 million for high-dosage tutoring this fall. The state also plans to use what’s left of the $4 million in federal relief funds that they’d hoped to spend last school year to support math tutoring for middle school students.

Data shows New Mexico students still have a lot of ground to make up to combat pandemic learning loss. The state ranked last in fourth grade math and reading in the most recent iteration of the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

The experience underscores the difficulty of pulling off a statewide tutoring effort — even one backed by convincing research and millions of dollars in federal relief funds.

At a May tutoring conference at Stanford University, Education Secretary Arsenio Romero spoke candidly about the state’s false starts.

“Sometimes we as educators are our own worst enemies,” he said. “We go through year-long cycles before we … make changes. You need to be able to pivot.”

‘All the way to the living room’

Especially when the needs are so great.

On state tests, less than a quarter of New Mexico students meet math standards and just 38% score proficient in English language arts. The state also continues to operate under a 2018 court order to improve education for English learners and low-income, special education and Native American students.

In late 2022, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham announced the state had signed a $3.3 million contract with Paper, a virtual, on-demand tutoring company. The deal promised to offer students in high-poverty elementary and middle schools — those hit hardest by school closures — up to 20 hours of free tutoring.

But the state abruptly terminated the contract less than three months later. The model expected families to sign up for help on nights and weekends, which research shows doesn’t often reach students who are furthest behind. Those students might not know the right questions to ask a tutor, and technical glitches associated with online programs tend to frustrate both kids and parents who are already discouraged.

“This service is not providing the results in terms of engagement, support or delivery of service to the state’s students,” Mariana Padilla, then-interim secretary of education, wrote to the company.

Montaño in Bernalillo doesn’t think any students in his district signed up for the program. “Deployment from the state level all the way to the living room of families is a hugely difficult process,” he said.

Paper officials cited multiple reasons for the rocky rollout. The program launched just as students returned from holiday break in January 2023, and the state didn’t give the company enough time to get buy-in from families and schools, said spokeswoman Ava Paydar.

Re-envisioning tutoring

Romero, appointed secretary by Lujan Grisham in March 2023, faced the immediate challenge of finding a more-effective tutoring provider.

“It really … allowed us to re-envision what we wanted tutoring to look like,” he said at the Stanford conference.

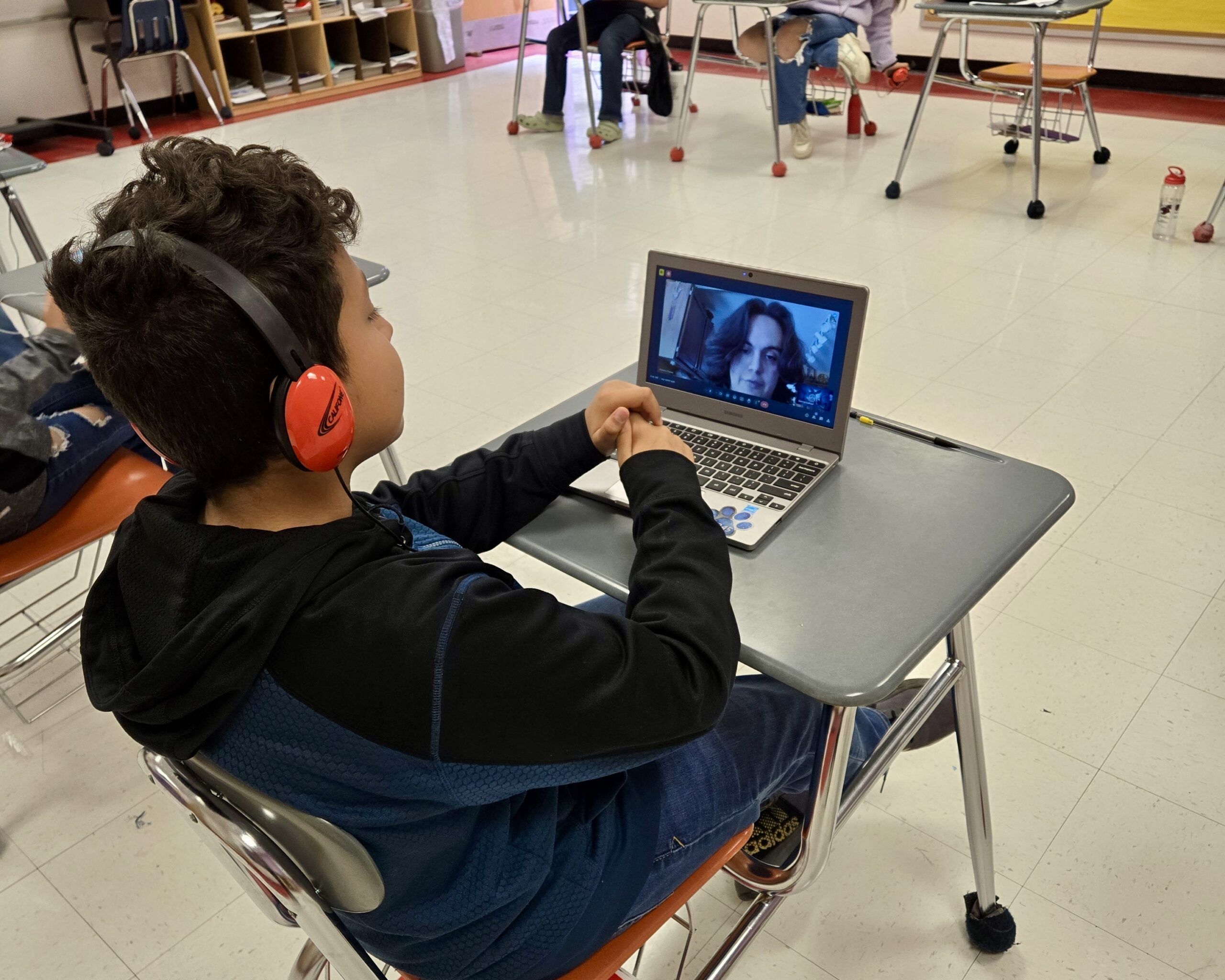

Three months after it canceled Paper’s contract, the state education department put out a call for vendors who could offer a high-impact model, either in person or virtually. The virtual classes that predominated during the height of the pandemic set students back academically by months, even years. But research shows that live instruction from a tutor working remotely can produce positive results if schools schedule sessions during the school day and offer the same consistent and frequent support as an in-person tutor.

The state chose three providers, who were slated to begin serving students last August. But officials abruptly canceled that program before it got started because of a protest from another vendor that wasn’t chosen. The department declined to explain the nature of the dispute, and Romero said the education department never finalized contracts with the three providers.

Some education advocates grew impatient as they watched the school year go by without a program in place.

“We failed to offer consistent access to quality, high-impact tutoring,” said Amanda Aragon, executive director of NewMexicoKidsCAN, part of a national network of education policy and advocacy groups. She called the spring effort “in no way sufficient.”

While New Mexico may have faced more obstacles than most, other states trying to provide tutoring to thousands of students have weathered similar ordeals.

New Jersey was slow last fall to get funding to districts to hire tutors, and Virginia initially got a lackluster response from districts when Gov. Glenn Youngkin announced his new All in VA plan, which includes high-impact tutoring in third through eighth grades. In Louisiana, some vendors passed on participating in a program that pays $40-per-hour for one-to-one sessions — about half what providers normally charge.

“Any state that was ambitious enough to take on large-scale implementation of tutoring has experienced growing pains,” said Nakia Towns, chief operating officer of Accelerate, a national initiative funding tutoring programs and research. Many have struggled to find high-quality vendors and convince districts to participate.

With the new state funding, New Mexico is trying something different. The state will provide the money, but districts will issue their own contracts and have flexibility to hire teachers or choose the outside vendors they want.

District efforts

One reason New Mexico leaders ultimately changed course is that they saw proof that districts had succeeded in blending tutoring into the school day.

Ten Las Cruces schools participated in a program this past school year with Tutored by Teachers, a virtual model led by credentialed educators. Students who were a grade level or more behind gained roughly twice as much learning as those who didn’t get tutoring, leading the district to invite the provider back this fall, said co-founder Rahul Kalita.

Romero visited one of the district’s schools in October and saw Spanish-speaking students practicing their English skills with a bilingual tutor while also getting math support.

Kalita attributed some of the state’s prior difficulties to a lack of “steady leadership” at the top. Romero is New Mexico’s third education secretary since 2019.

“Funding is critical, but it’s just the first step,” he said.

Further evidence on in-school tutoring comes from a study on a virtual model that has helped prepare over 500 New Mexico middle school students for high school algebra. The program, continuing this fall, is used in large districts like Chicago, Miami-Dade and Fulton County, Georgia. In New Mexico, the effort includes 19 districts, many of them small and isolated, like Tatum Municipal Schools.

Located about 15 miles from the Texas border, the rural district had just 26 seventh graders last school year. All of them received tutoring, and over half met or exceeded goals by the spring. That’s a small improvement over their scores from sixth grade, said Superintendent Robin Fulce, but he considers that progress significant because of the “big jump” in rigorous material in seventh grade.

The program has convinced Fulce that students can form tight relationships even with tutors they meet online.

Recently, two of those tutors passed through town for a visit.

“They brought doughnuts and every kid in that seventh grade went over and hugged them. “It was a very good experience,” Fulce said. To him, the state’s multiple tutoring efforts reinforced that offering services outside the school day doesn’t benefit “kids who need it the most.”

The results, Romero said, influenced the state’s decision to shift gears and make “decisions based on research and data.”

Montaño, the Bernalillo superintendent, estimated that about 800 students in his district received services — roughly half those he felt should have gotten the support. But he doesn’t consider it a wasted effort.

“It was too good of an opportunity for us not to take advantage” of it, he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)