An Education System, Divided: How Internet Inequity Persisted Through 4 Presidents and Left Schools Unprepared for the Pandemic

By Kevin Mahnken | May 5, 2020

As COVID-19 shut down its schools, Hamilton County, Tennessee, was ideally situated for the switch to virtual learning. At least in theory.

Home to the regional tech hub of Chattanooga, Hamilton County has been celebrated for its pioneering, municipally owned fiber-optic network and the economic revival it has powered over the past decade. The area’s schools have played their part as well, launching an initiative to provide every student access to a Chromebook beginning in sixth grade. Even as classrooms began migrating online in March, the district’s coordinator of instructional technology, Greg Bagby, oversaw a push to lend out more laptops to families splitting their home computers between online school assignments, parents’ work responsibilities and incessant Netflix bingeing.

There was a hitch, though: About one-quarter of local students, particularly those in the county’s rural north, don’t have high-speed internet at home, forcing some parents to set out in the middle of the workday in search of parking lots where their kids could use free Wi-Fi. Local authorities leaped into action, quickly seeding the community with 27 wireless hotspots, but their work was delayed when a series of tornadoes ripped through Chattanooga on Easter Sunday. In the meantime, schools are delivering printed homework packets — what Bagby calls “treeware” — where they are needed.

“It’s hard for the teachers to figure out exactly how to live in both the digital and analog world, and we’re doing the best we can,” he said. “There are some things we just cannot do with pencil and paper that we can do with a device.”

The case of Hamilton County, a remarkably forward-looking area still adapting to the COVID shutdown, reflects a fundamental unfairness of American life: Access to the internet, the most vital technological resource imaginable in the present circumstances, is walled off from vast swaths of the country.

Before 2020, it would have been nearly impossible to foresee the emergence of a novel, fast-spreading plague forcing school authorities to cease regular operations and move to a universal model of distance learning. But the longer story of how millions of families were left unequipped to adapt to that model — scouring for wireless signals in churches and McDonald’s — developed over decades. Its origins implicate both the public and private sectors in a prolonged failure to extend the blessings of modern technology to countless Americans. Experts and government officials who have worked around the issue for over three decades told The 74 that internet providers haven’t sought to compete in poor and hard-to-serve communities, resulting in higher prices and narrower choice. And when it has acknowledged the problem at all, government has addressed it inadequately, through patchwork programs conceived largely during the time of landline telephones.

The existence of this fissure has long been perceived as a niche problem, receiving attention only sporadically outside the jargon-heavy circles of telecommunications policy. The millions of predominantly low-income Americans without reliable internet connectivity, living in rural and urban homes alike, are said to inhabit a “digital divide”; students who can’t log on to supplement their studies fall into a “homework gap.”

“I think the large-scale tolerance for inequity in this country gave rise to an inequitable telecommunications system.”

—Shelley Pasnik, director of the EDC’s Center for Children and Technology

But today, with more than 50 million schoolchildren receiving education outside of school, what was once esoteric has become existential. For most, no or limited internet access means a substantial reduction in learning, if not an outright halt. In a recent survey of more than 5,000 teachers, 55 percent said that less than half of their students were attending the online classes made necessary by COVID-19. National media have surfaced similar accounts of disadvantaged and special needs students unable to receive schooling, all while education observers wonder how it is possible that the digital divide has persisted this far and caused this much harm.

The clearest manifestation of that harm is the reproduction of inequality. Cleavages of class, race and geography have been carried over from the physical world to the internet, conceived by its creators as an egalitarian space offering information and opportunity to all. The neediest students, who stand to benefit the most from the learning opportunities the internet provides, are the least likely to experience them. Shelley Pasnik, director of the EDC’s Center for Children and Technology, sees the digital divide as a mirror of more fundamental injustices.

“I think the large-scale tolerance for inequity in this country gave rise to an inequitable telecommunications system,” she said in an interview.

Bagby said that while his district has risen to the challenge of transitioning to online instruction, it pains him to consider how many children are still separated from their classmates and teachers by virtual barriers, both in Tennessee and across the country. The failure is captured in the fragmented image of a Zoom classroom, where adjoining windows show children living and learning in vastly divergent homes — if they’re able to make it to class at all.

“They’re in the Zoom meeting together, one person living in poverty and the other living in luxury. And that’s happening with the folks that actually have the devices. Just think about taking the device away. … Think about those kids that are missing it, and your heart goes out to them, because they’re part of a group that’s going to get left behind.”

Lost in the ‘information superhighway’

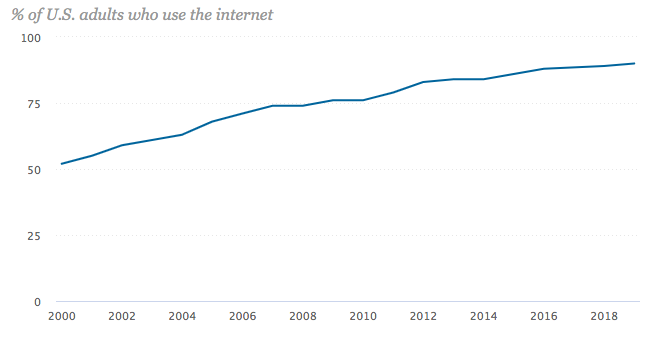

The uneven distribution of internet users has never been a secret. In fact, technology leaders in government noticed it by the middle of the 1990s.

“In those days, if you were a fireman or a policeman, or you owned a grocery store, you weren’t using the internet — but if you were a lawyer or a doctor or a professor, you might have it,” said former assistant commerce secretary Larry Irving. “So the divide was a gap of class and income.”

Irving served for seven years as administrator of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, becoming one of the main architects of telecommunications policy in the Clinton White House. He came to the executive branch after working on Capitol Hill as legislative director for U.S. Rep. Mickey Leland. In 1985, the Texas Democrat and former anti-poverty activist was instrumental in creating Lifeline, the first federal program to subsidize home telephone service for the poor.

The birth of Lifeline was an acknowledgment that national telephone penetration rates were lower for poor and minority consumers. With the millennium approaching, technocratically inclined policymakers like Irving worried that the same disparities would be reinscribed on the budding realm of cyberspace. The goal of the incoming Clinton administration — part of its oft-invoked mandate to build a bridge to the 21st century — was to hasten the spread of internet usage in every corner of American life, including education.

“At the time, the internet was kind of a hobbyist initiative, basically people using things like Compuserve and AOL,” Irving remembered. “President Clinton and Vice President Gore said, early on, ‘We’re going to make sure that every school, hospital, library in America is connected to the internet.'”

To that end, it successfully pushed for the enactment of the landmark Telecommunications Act of 1996, the first comprehensive overhaul of the industry since the New Deal. The law lowered regulatory barriers to media concentration with the aim of broadening access and lowering prices.

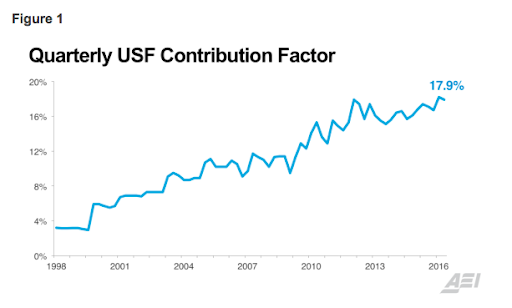

It also authorized the program commonly known as E-Rate, which allowed schools and libraries to receive internet service at discounts of up to 90 percent. To pay for the initiative, the new law codified a Universal Service Fund, financed by mandatory contributions from telephone companies (which are, themselves, passed on to customer telephone bills). Though originally capped at $2.25 billion per year, E-Rate’s subsidies would grow in the coming years as the program linked more classrooms to what was still breathlessly described as the “information superhighway.”

Nicol Turner-Lee, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Technology Innovation, was an early witness to the internet’s extraordinary pull on young people. As a graduate student in Chicago in the late ’90s, she helped establish several community technology centers — another flight of Clintonian ambition funded throughout the country by Education Department grants. The centers were designed to bring computers and internet access into underserved spaces, and Turner-Lee periodically found herself helping students with their homework in churches and public housing. Over 20 years later, she described the elation they felt when presented with a shipment of Encarta virtual encyclopedias.

“I remember taking them out of the box and these kids going crazy because none of them had grown up in a house like mine, where we had an encyclopedia collection every year,” she recalled. “At the time when Encarta came out, in gang-ridden Chicago, a lot of these kids weren’t comfortable going out to the library. It opened up a whole world that did not exist for them before.”

At the same time that internet activity was exploding, Irving’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration kept assiduous track of user demographics in a series of reports called Falling Through the Net. In each volume, the agency noted alarming breaches in telephone and internet penetration that were dividing society into “information haves and have-nots.” The 1999 dispatch found that a two-parent family earning more than $35,000 was between two and six times as likely to have home internet access as a similarly situated family making less than that amount.

But increasingly, Irving found himself discouraged from flagging those trends, and even from using the phrase “digital divide” in official publications. Senior officials in the Department of Commerce believed it to be “a fractious term,” he said, in part because “it disparaged this new Information Age that was being created.”

Irving added that the disapproval came even from Commerce Secretary Bill Daley, leading him to directly petition President Clinton’s office for permission to keep banging the drum. It was ultimately granted, but Irving was searching for other jobs before long.

“Mr. Daley was not a fan of the term,” he said. “It was not a coincidence that I left shortly after that last report.”

Daley’s office did not respond to a request for comment from The 74.

The Clinton presidency reached its end soon after, and on a melancholy note for its techno-enthusiasts; rather than being succeeded by Vice President Al Gore, a true believer who had trumpeted the internet’s potential going back to the 1980s, the president was ushered out of office by Texas Gov. George W. Bush. Mark Cooper, research director of the nonprofit consumer advocacy consortium Consumer Federation of America, said that the administration’s expansive designs, and its nascent focus on inequities in internet access, were ultimately unfulfilled.

“We were having this great debate about the divide because it was quite clear that connectivity was income-dependent,” he said. “The Clinton administration talked about it, they used the concept, [but] they never did much about it. Al Gore was going to fix that; well, we didn’t get Al Gore.”

An era of missed opportunities

The first mention of a digital divide came early in the new Bush administration.

In his first press conference, newly designated FCC chair Michael K. Powell invoked the problem of unequal internet access — though only jokingly, analogizing it to a “Mercedes-Benz divide: I’d like to have one, but I can’t afford it.” He went on to concede the importance of the issue but argued that the expectation of rapid, equivalent access to technological innovation for all of society verged on “the socialization of deployment of infrastructure.”

The remark was interpreted as a signal that concern about unequal connectivity would be much more muted under Bush. Irving considers the era to be one of missed opportunities, during which “the digital divide, both rural and urban, was ignored for an eight-year period.”

The change in direction was anticipated by Bush’s 2000 campaign, when he promised to block-grant nine different educational programs, including E-Rate, in a single fund to be distributed to the states. The suggestion spooked the initiative’s supporters, who warned that it would mean stepping back from the effort to bring schools and libraries online. While the move never took effect, Bush did consolidate or shrink several Clinton-era education and technology programs.

E-Rate survived the reshuffle and saw its footprint grow, with 30,000 schools and libraries applying for discounts each year. But beginning in the early 2000s, it was also targeted by FCC investigations that brought to light serious financial improprieties and governance issues. One report memorably alleged that E-Rate was “honeycombed with fraud and financial shenanigans.” Republicans began referring to the beleaguered program as a “Gore tax” lurking at the bottom of your phone bill.

And while an increasing share of Americans were going online to work, shop and play games, the goal of bringing high-speed internet to every American home went unrealized. When Bush began pledging, during his re-election campaign, that his administration would wire “every corner” of the country by 2007, observers noted that it was the first time he had spoken about broadband in nearly two years.

High-speed internet spread widely over the same period, especially in the middle-class suburbs, and smartphone-crazed Americans began consuming ever-greater quantities of data. Pew Research found that the proportion of Americans who said they used the internet every day rose from 55 percent in 2001 to 74 percent in 2008.

But during those years, and even into the decade that followed, some sections of the country — notably rural and low-income communities, and especially places where those designations overlapped — saw much lower broadband subscription rates. One recent study found that, in 2015, roughly one-quarter of Americans lived in neighborhoods where fewer than 40 percent of households had broadband. Nearly 18 million school-age children lived in such neighborhoods.

To many technology advocates, those coverage gaps are evidence of a market failure: Big internet service providers like AT&T, Comcast and Spectrum are less likely to compete against one another in rural areas, where it costs more to provide services to fewer customers. In the words of Brookings’s Turner-Lee, if you live in a locale deemed undesirable by such companies, “your choices are slim.”

A damning Wall Street Journal analysis of thousands of telephone bills from all 50 states found that residents of rural and low-income communities received slower internet speeds while paying similar prices to their more affluent and urban counterparts. Moreover, in the vast majority of cases, the customers had no second option of a fiber or cable internet provider.

Providers, the Consumer Federation’s Cooper remarked simply, “will not go where profit is not sufficiently attractive. They don’t go to high-cost areas like rural America, and they don’t go to lower-income areas; it costs too much to serve the former, and the latter is not an attractive market.”

To Thomas Hazlett, who served as the FCC’s chief economist under President George H.W. Bush, that’s faulty reasoning. A longtime skeptic of universal service programs like E-Rate, he said it was only logical that high infrastructure costs deterred some companies from offering more and better service in hard-to-reach communities.

“It’s not a market failure to have the market not provide a service where customers are not willing to pay its cost of provision,” he said. “In fact, you don’t want suppliers to waste society’s resources by doing that. And that means that not every place in Alaska is going to be wired for fiber to the home. That’s actually what the market’s supposed to do.”

But some students in Placer County, California, experience patchy internet access as a major stumbling block. Superintendent Gayle Garbolino-Mojica has spent the past month attempting to transition the county’s roughly 73,000 students, spread over 19 school districts, to online learning. Most of those districts fall in the suburbs outside Sacramento, where, as she said, “we have a couple of [broadband] plans available.” But farther east, where bedroom communities give way to the mountain towns of what used to be called the Gold Country, some families get by with glacial internet or none at all.

“It’s not a market failure to have the market not provide a service where customers are not willing to pay its cost of provision. In fact, you don’t want suppliers to waste society’s resources by doing that. And that means that not every place in Alaska is going to be wired for fiber to the home. That’s actually what the market’s supposed to do.”

—Thomas Hazlett, the FCC’s chief economist under President George H.W. Bush

“Probably 10 percent of our population is [in] more remote areas, and their connectivity is either very limited or, in some cases, nonexistent,” Garbolino-Mojica said.

The abruptness of California’s school shutdown caught local leaders unaware, producing an arms race for much-needed devices that pitted districts against one another. While Garbolino-Mojica immediately contacted her distributors to procure as many as she could, COVID-fueled demand now greatly outstrips the supply. According to one recent report, roughly 200,000 California households with school-age children are currently without the computers and/or hotspots they need.

“I had a Montessori charter school in our county call last week,” she said. “They said, ‘Turns out I’ve got a kid who spends half his time with Mom and half with Dad. When he’s with Mom, he has internet, but not when he’s with Dad. Can we just get one hotspot?’ And we could not find one. We’re all exhausted and waiting for shipments.”

Along with other county superintendents, Garbolino-Mojica makes semi-annual trips to Washington, D.C., to lobby national politicians to spend more on local priorities like Head Start and the Individuals with Disabilities Act. Initially she questioned the necessity of their trips to meet with FCC staff.

“When they’d say, ‘We’re going to the FCC,’ I’d go, ‘Ugh, why? Can’t we just go to the Hill and talk to some congressmen?'” She subsequently learned what was motivating the advocacy; between 15 and 20 percent of families in Placer County are eligible to receive telephone discounts under the Lifeline program.

Hazlett, who has written scathingly of the cost of federal internet subsidies, is nevertheless concerned about the situation facing students stuck at home with no way to access teachers or classmates. His own niece, a high school senior who had recently moved across the country, found herself without broadband access when her school closed. She was able to visit his home until the situation was resolved, but many others won’t be as lucky.

“They couldn’t get anybody to come out and hook them up, so she came to our place and spent the last week because we have internet access,” he said. “If your parents don’t have internet access, then how are you supposed to perform against your peers in the classroom? That’s been going on, and now it’s forced on millions of students.”

‘They need to do whatever it takes’

In the first decade of the new millenium, some thought was given to the prospect of a wide-scale disaster, either natural or man-made, that might threaten communications networks and shutter schools for longer than a few days. Several such events — the 9/11 attacks and subsequent anthrax scares, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 — offered previews of the COVID era. But planning for a response “was primarily a hodgepodge of different organizations and groups at the local level,” said Thomas Chandler, a research scientist at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University.

It was only in the first few months of the Obama administration, when a swine flu pandemic closed more than 700 schools across the United States, that school districts began to reckon with the limits of their continuity-of-operations planning.

“After the H1N1 pandemic in 2009, a lot of those plans were activated in different schools, and more schools began to adopt that as part of their planning processes. But it was really only from a logistical standpoint, rather than focusing on the aims of what a distance learning program would actually be for the long term, or what learning outcomes would be. There was this lack of a needs assessment to determine who would actually have access, what is the digital divide in the community, what students wouldn’t be able to log in at all.”

In a broader sense, Obama’s election brought a return to more muscular interventions to spread home broadband. But they seemed to be buried under a heaping progressive agenda that included health care reform, climate change, Wall Street regulation and, even within telecommunications policy, a lengthy debate around the issue of network neutrality.

In his last years in office, the administration launched a pilot program that offered low-cost wireless internet, digital literacy classes and steeply discounted devices to 275,000 households in 27 cities. By the spring of 2016, Obama had set a goal of subscribing another 20 million Americans to broadband by the end of the decade; in his announcement, the president specifically cited the need for students “to get online, no matter where they live or how much their parents make.”

Most importantly, the FCC voted to expand Lifeline to cover stand-alone broadband. The decision would theoretically give millions more people access to affordable internet at home, but it came after an enervating fight in Congress, where Republicans branded the Reagan-vintage initiative an “Obamaphone” giveaway and loudly considered defunding it.

Hazlett has been particularly critical of the Obama-era FCC’s decision to increase the yearly cap on E-Rate spending, especially after finding in a 2016 study of North Carolina high schools that the program’s subsidies were not correlated with student achievement gains. On top of that, he added, is the central irony of the COVID shutdowns: After spending billions of dollars over several decades to wire schools, virtually every student in the United States is now shut out of them.

“We’ve had a very big investment in subsidizing internet access for the schools,” he said. “Multiply $2.25 billion a year since shortly after the 1996 Telecommunications Act — you’re almost at 25 years on that, and it’s since been increased in the last few years — plus interest and whatever else. And as I’ve found, as just about anybody who’s objectively looked at the system has found, that money has been largely wasted.”

Even vocal defenders, such as Democratic FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel, have argued in favor of revamping the initiative to connect schools and libraries. While celebrating E-Rate for helping connect 95 percent of public schools to the internet (compared with 14 percent in 1996), Rosenworcel has pushed for reforms to ensure better governance and less fraud.

Other commentators, like Boston College law professor Daniel Lyons, object to the FCC operating the programs (and their revenue source, the Universal Service Fund) outside of the congressional appropriations process. Partly because the funding takes place, as it were, off the books, the surcharge on customers’ phone bills has grown from 3 percent in 1998 to nearly 25 percent today — akin to “the tax cities put on hotel rooms to fleece out-of-town suckers,” in Lyons’s reckoning.

Much of what Lyons objects to in the federal government’s digital strategy has to do with what he considers the ad hoc way in which policy has evolved. The 1996 Telecommunications Act was passed when the internet had barely gained public acceptance, and broadband — let alone mobile technology — was barely a glimmer. Lifeline is a benefit originally intended to expand access to landline phones, its $9.25 monthly subsidy offering recipients paltry choices when selecting internet service.

In response to the program’s recent expansion, Lyons has advocated overhauling it into a targeted voucher system — perhaps even a more generous one, including costs for home computer equipment that many low-income consumers lack.

“I’m a right-of-center guy, but I do think that there is a role of government to play in closing the digital divide,” he said. “My biggest critique has been that the role that government has played thus far has not been a smart one. Much of what’s happening seems to fall under the syllogism of ‘We need to do something, here’s something, let’s do it.’”

Irving said that the resistance to a program of Lifeline’s modest scope was a reflection of a political divide pitting rural areas against cities for technology resources. Republican legislators were sympathetic to the connectivity needs of farmers and small towns, he said, but when it came to Lifeline, which is designed to serve poor people, they combed budgets for evidence of scandal. Ads lampooning a Black “Obamaphone lady,” aired by the Tea Party during Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign, contributed to the program’s marginalization by inflaming political prejudices, he said.

“I’ve got 15-20 million urban and suburban Americans who can’t afford broadband internet, and that program is being nibbled to death by ducks,” he said. “There’s this thing about waste, fraud and abuse, and welfare cheats, and it has to do with low-income people. It has dynamics to it — race, class, education — that are just unfortunate.”

Skepticism toward Lifeline has extended into the Trump White House as well. FCC Chairman Ajit Pai speaks much more openly about the existence of the digital divide than his Republican predecessors, but one of his first moves was to reverse an earlier decision that would have allowed nine new companies to participate in Lifeline. Last year, reports surfaced that hundreds of E-Rate applications from schools were stuck in “limbo” due to a cumbersome review process.

“They need to do whatever it takes to make sure that they can get learning into the homes of these kids. We haven’t been thinking creatively. If the Department of Health can set up tents in Central Park with hospital beds and air systems and drive-up testing sites, and we can’t find ways to promote internet access for our kids to get online for school, then we’ve failed.”—Nicol Turner-Lee, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Technology Innovation

Even the spread of coronavirus has not yet produced agreement over what measures are needed to connect students to virtual learning while their schools are locked down. While the House of Representatives allocated $2 billion to E-Rate for remote learning in their original stimulus proposal, the funding boost didn’t make it into the law signed by President Trump.

In the meantime, districts are attempting to patch holes at the local level. Placer County’s Gayle Garbolino-Mojica said that parents in her most far-flung districts have been willing to sit in school parking lots while their children use free Wi-Fi to finish homework assignments.

“I have a small rural school district of less than 100 kids, and a great percentage of their students don’t have access to reliable internet,” she said. “The superintendent has had to be really creative and say, ‘A family of four can come into the school on X, Y and Z days at times when no one else is here to do online learning.’”

Other leaders have sent school buses into largely unwired neighborhoods to act as mobile hotspots. Big districts like Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., have made use of public television as a delivery mechanism for lessons. Pasnik, of the Center for Children and Technology, pointed to the experience of schools in Africa, many of which relied on radio stations to broadcast educational content while students were kept out during the Ebola outbreak of 2015.

“This is definitely a time to think creatively about what tools we have, what tools are in people’s pockets and homes,” she said. “Broadband television can be that, and radio can be that. It’s unfortunate that it’s happening in a very ad hoc way, but it also speaks to the tenacity and spirit of many educators.”

Turner-Lee said that the pandemic showed clearly that a more ambitious approach was necessary to connect students with online learning opportunities. Once the crisis passes, she said, educators and policymakers should adopt some of the urgency shown by the public-health sector to solve a problem that has lingered too long.

“They need to do whatever it takes to make sure that they can get learning into the homes of these kids. We haven’t been thinking creatively. If the Department of Health can set up tents in Central Park with hospital beds and air systems and drive-up testing sites, and we can’t find ways to promote internet access for our kids to get online for school, then we’ve failed.”

Lead photo: Jackson Federico, a tower technician for Advanced Wireless Solutions, works to make some repairs on the dish on the Pollard cell tower high off the ground in rural Rio Blanco County on July 12, 2017, near Meeker, Colorado. Broadband in Rio Blanco county and Meeker is some of the best in the state for rural areas. (Helen H. Richardson/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter