Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

What are the consequences of closing virtually every American school and shifting to online education for months at a time?

It’s a question that education experts have been asking since the emergence of COVID-19, and one whose answers are gradually becoming clearer. With federal sources reporting that 99 percent of students have now returned to classrooms, newly available data are showing how students were affected by spending long stretches of the last two school years at home. And the signs are not good.

Perhaps the most disturbing news yet was found in a working paper released last month by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which found that state test scores dropped significantly in both reading and math during the pandemic. In a discovery that will reopen questions about the wisdom of keeping schools closed, economist Emily Oster and her co-authors found that learning loss was far worse in districts that kept classes fully remote, and that declines in reading scores were greater in districts serving predominantly poor and non-white students.

Oster, a Brown University professor and popular author, has won both adulation and criticism in the COVID era as an advocate for school reopenings. One study she co-authored, examining the spread of coronavirus in 250 Massachusetts districts last winter, helped persuade officials at the Centers for Disease Control to reduce the recommended social distancing requirement in schools from six feet to three.

In an interview, Oster said that while the pandemic’s academic impact was “probably larger than [she] expected,” the differential effects related to closure policy were not unexpected.

“Certainly I do not find the direction surprising, or the fact that there was a significant difference across these groups,” she noted.

The study makes use of two huge sources of information. One, the COVID-19 School Data Hub, was launched in September by Oster and her colleagues to track the different learning models (virtual, in-person, or hybrid), enrollment trends, and public health outcomes that prevailed in schools during the 2020-21 school year.

The other was assembled from the 2021 math and English scores for students in 12 states between the third and eighth grades. The states studied (Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming) were chosen because their student participation rates in state tests remained above 50 percent this spring, and they offered at least two years’ worth of testing data from the period before the pandemic.

The researchers found that overall student pass rates — the rate at which students score at or above “proficient,” however that is designated by the state administering the test — dropped in all 12 states, though with a wide variation in the size of the declines. In Wyoming, pass rates fell 2.3 points compared with prior years; in Virginia, they plummeted by 31.9 percent.

What’s more, the scale of learning loss was far more substantial in areas that kept schools closed longer.

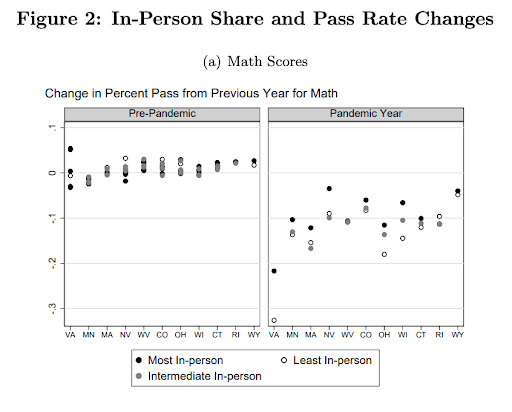

The team specifically targeted the effects of school closures by dividing all school districts in their sample into three groups: those that offered in-person learning for at least two-thirds of the 2020-21 school year, those that went in-person for less than one-third of the year, and those that fell somewhere in-between. Then they compared changes in test performance among schools that fell into the different categories.

The total effect of a district shifting from 0 percent in-person learning to 100 percent would be to reduce the drop in math pass rates by 10.1 percentage points (or more than two-thirds the average amount they declined during 2020-21, 14.1 points), Oster and her collaborators calculated; the same change would reduce the drop in English pass rates by 3.7 percentage points (more than half the average amount they declined over the same period, 6.3 points).

The downward movement on achievement was also somewhat linked to student background. By indexing the decline in scores to district demographic information, the authors found that in districts that enrolled over 50 percent African American or Hispanic students, the effect of switching from fully in-person classes to fully remote was associated with a drop in pass rates of 9 percentage points. Meanwhile, in a district enrolling no African American or Hispanic students, that switch only brought about a drop of 4.3 points.

Those disparate trends find support in other research. Recent results from the online i-Ready assessment, administered to over 3 million elementary and middle schoolers across 50 students by Curriculum Associates, showed that students in majority-African American schools have fallen behind those in majority-white schools by a full 12 months of learning during the pandemic. Black students, on average, have enjoyed much less access to in-person classes during that time, studies have demonstrated.

One lingering question is the extent to which the results were influenced by the cross-section of students who sat for tests this spring. With a sizable number of students either opting out of state-required testing or simply leaving public schools entirely, some have wondered whether the students who participated in the exams offer a representative sample from which to draw conclusions.

Oster said that the high participation rates in states that were selected for the study (all above 80 percent, and most above 90 percent) gave her “more confidence” in the effects she found. If anything, she said, the groups that were underrepresented in spring testing — disproportionately English learners and special education students — made it likely that the study was underestimating the damage wrought by the pandemic.

“You see pretty consistently across states that there was less participation among English language learners or special ed students. That makes me think that…these numbers could be even larger if we sampled those groups at higher rates also.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)