Returning this Fall, By Popular Demand: Virtual School. For Communities of Color, it’s Largely a Matter of Trust

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

As more Americans receive Covid-19 vaccines and schools move to reopen widely, leaders are doing their best to make sure everyone gets the memo: School is happening in-person this fall.

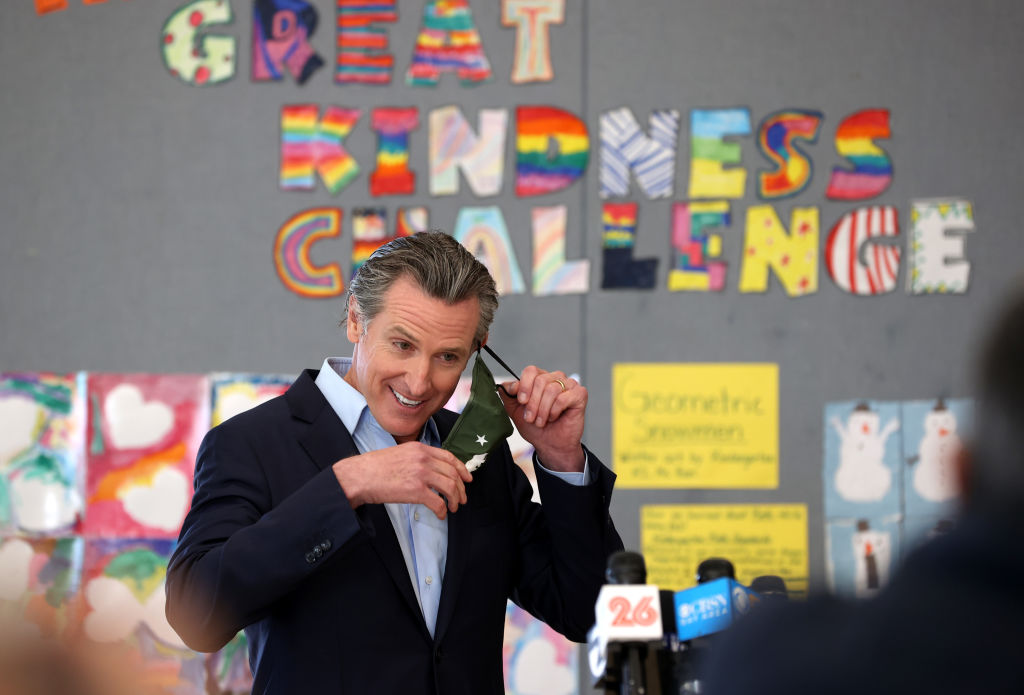

California Gov. Gavin Newsom recently told reporters, “We must prepare now for full in-person instruction come next school year.”

In New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy said in March he is “fully expecting” schools across the state to return in-person in the fall, no exceptions. “We are expecting Monday through Friday, in-person, every school, every district,” he said.

Good luck with that.

Even as vaccination rates soar and the government authorizes access for adolescents, school districts nationwide are grappling with sometimes widespread suspicion and dissatisfaction over how they handled the pandemic, especially in communities of color. That’s forcing them to offer families an option that might have been unthinkable a year ago — and one that has a terrible track record: enrolling their children online this fall and continuing learning from home.

Dawn Williams, whose daughter will start first grade in August in Maryland’s Prince George’s County, said she’s seriously considering an online program. “Most of my friends that have children, their kids are still virtual,” she said.

So far it’s happening in just a fraction of the nation’s 13,500 districts. But those include a wide mix of rural and suburban districts, as well as large urban school systems like Albuquerque, Atlanta, Cincinnati, Dallas, Indianapolis, Nashville, Omaha, Richmond, and the District of Columbia, according to the University of Washington’s Center for the Reinvention of Public Education (CRPE).

In Colorado’s Jefferson County, the school district, responding to “high demand” from families, recently announced an online option in the fall. District spokesperson Cameron Bell said more than 700 students have enrolled so far, with at least 1,000 expected by August.

In Montgomery County, the largest school district in Maryland, officials are developing a virtual academy “to address both the students who may want to remain virtual for health reasons but also those who have thrived in virtual learning,” said spokesperson Gboyinde Onijala.

What’s going on here?

Much of this can be chalked up to simple consumer demand. One recent Ipsos/NPR poll found that nearly 30 percent of parents would rely on virtual learning “indefinitely” going forward. That suggests a potential market of more than 15 million students.

Districts are listening. When RAND researchers surveyed about 320 public school leaders last October, they found that one in five were either considering or actually planning to keep “one or more virtual schools” operating after the pandemic ends, said RAND’s Heather Schwartz.

“I expect that to hold, or even to increase somewhat based on early anecdotal indications that a sizable minority of students and parents prefer remote learning,” Schwartz said via email.

More recently, in early April, researchers at CRPE surveyed officials in 100 large urban school districts and found nearly identical results: 23, or just over one in five, plan to offer a remote option next fall.

District leaders told Schwartz and other researchers that their main motivation was “to be responsive to parent and student preferences” — and in no small part to improve sagging enrollments. One analysis of 33 states by The Associated Press and the education news site Chalkbeat found that public K-12 enrollment in 2020 dropped by more than half a million students, or 2 percent.

“You keep hearing this word: ‘thriving’”

As he talks these days to school leaders nationwide, education consultant John Bailey said he hears many of them say they plan to make online learning “a more permanent part of their offering to kids going forward.” A one-time U.S. Department of Education official who now advises the Walton Family Foundation, Bailey has supported the idea that reopening schools is safe. He said that while many educators acknowledge millions of students lost ground via distance learning, “for some kids, it’s working really well. So why not offer that going forward?”

Nationwide, families of color are keeping their children home at especially high rates. In Chicago, the district’s chief of school management told school board members late last month that most students are “learning virtually.” But about one in four Black high school students was absent from both in-person and remote learning in late April. Overall, only about two-thirds of high school students attended in-person classes on days they were expected in school, the Chicago Sun-Times reported.

At the same time, Asian fourth-graders attend school remotely at the highest rate of any group — 95 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Eighth-graders attend at an even higher rate: 96 percent. Asian families have expressed fears about their children experiencing anti-Asian discrimination or even violence in the wake of the pandemic.

While state and local restrictions can play a part in attendance statistics like these, many families are simply voting with their feet, said Bree Dusseault, a practitioner in residence at CRPE.

“There’s still a really sizable population of students who, even when given the option to be in-person, aren’t taking it,” she said.

“You keep hearing this word: ‘thriving’ — particularly in families of color,” said Annette Anderson, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Safe and Healthy Schools in Baltimore. “Districts have never had to wrestle with ‘How do we provide education in multiple formats?’ They thought this was a stopgap. Now what I think they’re finding is that there are many parents that were just fine with virtual learning.”

Anderson, a Black educator who is also a mother of three teens, said the past year has taught parents “that they have a voice at the table – and they are not being shy and retiring about letting people know what they want in terms of how they want their children to learn.”

Recent survey data suggest that Black, Hispanic and Asian parents are more likely than their white peers to say they prefer online learning. For instance, the journal Education Next recently noted data from early April that showed 60 percent of white parents have a preference for in-person learning, compared to just 25 percent of Black and Hispanic parents.

At the same time, Dusseault said, many parents of color see how badly education systems have served their kids in the past, with substandard instruction and more aggressive discipline.

When Anderson surveyed her three children recently, none wanted to go back to their Baltimore school this fall. They like learning from home and have been successful.

“I think my kids sometimes miss their friends,” she said. “But aside from that, I don’t have any of my three children saying right now, ‘Mom, I want to go back to school today or tomorrow.’ They have adapted to this.”

Anderson was quick to add that her kids “have every kind of technology possible,” as well as space at home to use it. All three have their own rooms, plus their home has a backyard. But whatever their situations, she said, “There are a lot of kids who are at home and they’re thriving. You can’t negate the success of those students and the opportunity that they have had to be separated from their peers and still do well academically.”

Williams, mother of the Maryland first-grader, said her daughter is already doing advanced work — and she’d like to keep it that way. Giving her child a chance to work virtually and independently is key.

“Students that are more advanced — and parents that have the choice — we’re going to keep our kids home,” she said. “Those kids are going to accelerate. They’re going to soar and they’re going to keep advancing.”

“School hesitancy” and safety

Vladimir Kogan, an Ohio State University political scientist who studies politics and public policy, said “school hesitancy” may in part be a function of the messages families hear — especially in places where teachers’ unions loudly demonstrated last year, enacting mock funerals and the like to warn of the dangers of reopening schools.

“I think that messaging has definitely filtered down to the parents,” he said.

But recent research has shown that when prevention strategies are in place in schools, transmission of the virus is typically lower than, or similar to, levels of community transmission, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As a result, public opinion is shifting. A February Pew survey found that 61 percent of Americans said K-12 schools that weren’t open for in-person instruction “should give a lot of consideration to the possibility that students will fall behind academically.” That’s up from 48 percent last July. And fewer Americans said schools should give a lot of consideration to the risk to teachers or students.

“I think the number of parents who are hesitant is going to go down pretty substantially,” Kogan said. “But I don’t think it’s going to go down to zero.”

Bailey, who recently authored a study summarizing research on safe school re-openings amid Covid fears, predicted that there will be a group of parents “who will probably never feel that it’s safe until there’s a vaccine for kids.”

The prognosis on vaccines seems promising: This week, both the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved expanded use of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for children 12 to 15 years old. Pfizer also said it’ll ask the FDA for emergency authorization in September to administer its vaccine to children as young as 2 years old.

Both Johnson & Johnson and Moderna are conducting trials in children.The U.S. vaccine developer Novavax is also beginning trials on children — its vaccine has a reported 96 percent efficacy rate in adults and is awaiting emergency use authorization in the U.S.

A “really terrible” track record for virtual schools

Kogan, the political scientist, worries that by relying on virtual schools, districts are embracing a well-studied — and failed — reform.

In a 2019 literature review, researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder’s National Education Policy Center found that graduation rates at virtual and blended-learning schools were far lower than the national 85 percent average for public schools. The review followed years of similar findings from researchers nationwide.

In 2016, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, along with other groups, issued “A Call to Action” to improve their quality, saying far too many virtual schools “have experienced notable problems.”

At the student level, most of the dilemma lies in what’s required for students to be successful in virtual settings: huge amounts of self-control, motivation and discipline, said Kogan, who co-authored a report last January that found worse declines in reading achievement among Ohio third-graders in districts that used fully remote instruction.

The track record of these programs “was terrible before Covid,” Kogan said. “And I think it’s certainly the case that there are kids who do fine. But the districts are not saying, ‘We’re going to limit it only to kids who do fine.’”

To be fair, many educators get it. In its announcement of a “modified digital learning option,” the Gwinnett County, Ga., district last month offered an official warning: “Digital learning is not optimal for every student. Some students did not do as well academically, socially, or emotionally in the digital learning environment.”

In the long term, Kogan said, his larger worry is that this could open the door to a two-tier education system: a bigger, functional one for students whose parents are comfortable sending them to school, and a smaller, inferior one “for kids whose parents are too scared and keep them home.”

The long-term damage, he said, “is going to be so devastating. It’s going to exacerbate all the inequalities that we already have.”

Anderson, the Baltimore educator and mother, acknowledged the dilemma, but emphasized it was nothing new: Millions of kids weren’t being served well before the pandemic. Here’s a chance for something better, especially for students of color who are already staying away in large numbers.

While leaders may insist that everyone attend in-person on the first day of school this fall, Anderson said, “I’m not hearing what is going to significantly shift over the summer that is going to make sure that these large numbers of families of color are going to suddenly show up in September.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)