Boston Schools Escape Takeover but Must Show Improvement to State as District Enters Partnership

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Following the release of a harsh review alleging systemwide failures, education authorities in Massachusetts revealed last week that they would enter into a new governance partnership with Boston Public Schools, the state’s largest school district. While stopping short of an outright takeover, the move will impose new requirements on Boston schools to drastically improve.

The announcement, immediately overshadowed by the escalating nationwide response to the spread of coronavirus, will have profound consequences for the district’s 54,000 students. It also comes at a time of fast-moving reform in Massachusetts, where lawmakers enacted a massive and long-awaited school funding overhaul last fall.

The agreement was reached after weeks of negotiations between state Commissioner of Education Jeffrey Riley, BPS Superintendent Brenda Cassellius and Boston Mayor Marty Walsh. While the district will stay under local control, Riley will oversee its progress on a set of priorities ranging from transportation to chronic absenteeism — and retains the freedom to intervene if he deems it necessary.

Marty West, a professor of education at Harvard University and a member of the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, called the partnership unique.

“I’m not aware of other examples in which a state sets clear outcome metrics for a struggling district, backed by the threat of a takeover, while also committing to provide the district with specific supports,” he wrote in an email. “One of the things I appreciate about Commissioner Riley as a state board member is that he is an outside-of-the-box thinker.”

Amid a flurry of actions taken to slow the coronavirus outbreak — by the order of Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, all public and private schools in the state will close for three weeks starting on Tuesday — the novel solution hasn’t dominated headlines. But it may drive major changes to the city’s education system.

The state has not hesitated to initiate full-bore takeovers of local districts in the past, seizing control over chronically underperforming schools in Lawrence and Holyoke. Riley led the Lawrence takeover after being appointed the district’s receiver-superintendent in 2012 and has been credited with launching an impressive academic turnaround; Lawrence is now considered a model for successful takeovers, marked by cooperation between state and local officials.

Yet the situation in Boston — an economic powerhouse that commands sizable education revenues and boasts some of the strongest schools in the state — differs significantly from that of the low-income communities that have endured state intervention in the past. Experts have praised its robust charter school sector as the best in the country, and BPS has often been acclaimed as a top performer among big-city districts.

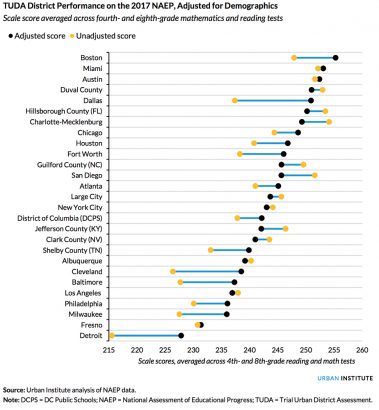

A January report from the Urban Institute using NAEP results offers the latest evidence. When controlling for socioeconomic status, students in Boston outscored those in all other districts participating in the test’s Trial Urban District Assessment.

But the nearly 300-page report filed on Friday by Riley’s team held starkly disappointing findings: Approximately one-third of all students in Boston attend schools that would rank in the bottom 10 percent statewide. Special education was described as being in “systemic disarray,” while “staggering” absenteeism and patchwork access to advanced coursework plagued high schools.

“The district does not have a clear, coherent, district-wide strategy for supporting low-performing schools and has limited capacity to support all schools designated by [the state] as requiring assistance or intervention,” the report revealed.

Going forward, BPS will take the lead on four priority initiatives laid out by the state, including turning around achievement in the district’s 33 underperforming schools, improving the school transportation system and doing more to support students with disabilities. The state, meanwhile, has committed to helping Boston recruit and retain a more diverse teacher workforce and foster partnerships between needy schools and outside organizations.

In a statement, the pro-reform advocacy group Massachusetts Parents United called the agreement “a beginning step toward improvement” but said its members had concerns that would need to be specifically addressed.

The announcement “does not include specific metrics for improvement, strategies for how its vague aspirations will be achieved, a timeline for when these aspirations will be reached, or any consequences if BPS is unable to improve the academic performance of its students,” the statement read. “Why should parents believe BPS will be able to do these things when it has never been able to do them before?”

Representatives from the Boston Teachers Union said it was “troubling” that the deal was reached when the state was still making emergency preparations for the coronavirus, adding that the district’s dysfunctions had been neglected by the state for decades.

“While the memorandum does not constitute a state takeover, it appears to leave the door open in ways that could be dangerous for students and our communities, given the failed track record of top-down district takeovers across the country.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)