The Band Teacher Who Kept His School Community Connected Through COVID’s Chaos

When students disappeared from remote learning, Alejandro Salazar tracked them down. Now he’s guiding them through a traumatic return to ‘normal’

By Bekah McNeel | May 3, 2022This is one article in a series produced in partnership with the Aspen Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project, spotlighting educators, mentors and local leaders who see community as the key to student success, especially during the turbulence of the pandemic. See all our profiles.

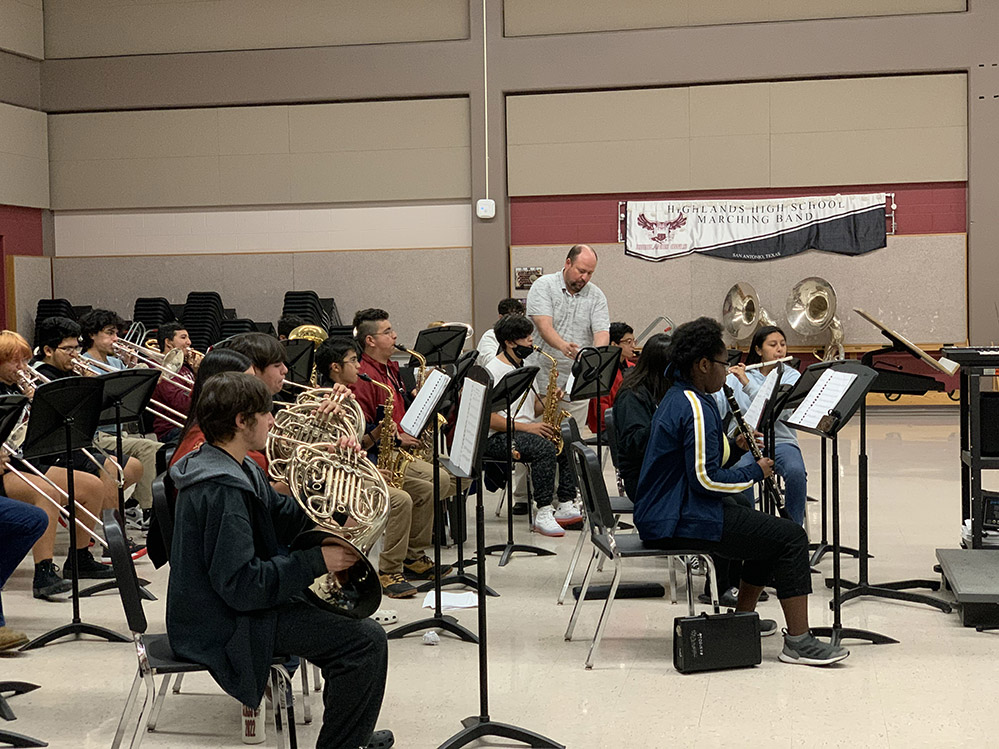

San Antonio high school band leader Alejandro Jaime Salazar knew something was off — really off — when he listened to the Mighty Owl marching band practice one morning this past winter.

Salazar, a tall man with a friendly face, even when concerned, walked between the rows glancing over shoulders, studying fingers to see what was wrong.

Finally he stopped them.

“Raise your hand if you’re on page six,” he said. To his surprise, most of the students in the Highlands High School band hall were not.

So, with a fluttering of pages, the Mighty Owls began again. It was better.

And it’s getting better all the time.

This kind of gaffe would have been pretty much unheard of years ago, when the band from Highlands High School in San Antonio consistently earned top marks in competitions, bringing home trophies, plaques, and ribbons.

But this school year, as the strain of the pandemic has worn on, and on, Salazar now says he takes mistakes in stride.

After all they’ve been through, all they are still going through, he says he knows it’s going to take time to get back on the same page and playing the same tune.

“They regressed a lot, but I’m okay with it because we brought them back,” said Salazar who spent the earliest days of the pandemic, March through May 2020, using every tool he had to hunt down more than 70 band members, stay connected to them over Zoom — sometimes with his own baby on his lap — and muster what enthusiasm he could to create structure, routine, and dependability in their lives.

Now that he has them back in the band hall, is able to check in on their mental health, can make sure they are eating and sleeping somewhere safe, he can start to revive their joy of playing, the thing that brought them together in the first place.

The entire U.S. school system has been in survival mode for the past two years, focused solely on getting kids back into buildings. Now, feeling as if they’re through the worst of it, one band teacher is determined to see his kids thrive again. “We’re bringing music back.”

Seasons of Love

In some ways, bringing the music back is a sign of hope and progress. Back in the spring of 2020 Salazar remembers being happy if he was able to get even a stanza out of his clunky Zoom practices, with his players waiting out the pandemic at home. He says most of his effort then went towards making sure everyone was safe — while some kids were juggling internet connections and noisy houses, others were facing food insecurity, newly unemployed parents, and mental health crises.

Salazar quickly realized that the band was often students’ strongest connection to school, and the essential resources it could provide — not just individual academics, but the community that was only as strong as its members.

But in other ways, bringing the music back doubled as a sign of just how much had been taken from the Mighty Owl Band over the last two years.

Sitting down with Salazar this past December, it was difficult to tell if it’s determination, weariness, hope or relief one now hears in Salazar’s voice. Maybe all of those, as he considers what it means to lead a marching band in the middle of a persistent pandemic and an escalating mental health crisis.

Salazar knows he probably won’t be adding much to the line of trophies in the Highlands High School band hall in southeast San Antonio — not this year, anyway. This year, it’s about using music to strengthen the bonds of the band, the same bonds he’s been relying on for almost two years to keep students within reach, safe from the ravages of isolation.

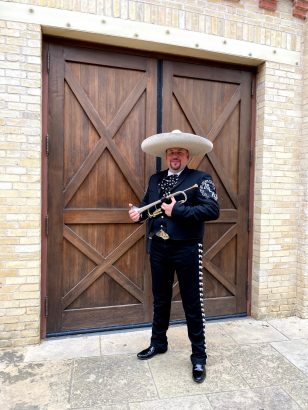

A lifelong performer, Salazar knows how close a band can be — he still plays trumpet with a group of mariachis. In fact, touring with a band was his original career goal. He eventually pursued teaching so that he could have a stable gig and start a family, and quickly realized giving students life experiences and confidence they didn’t have before was even more fulfilling than focusing on craft alone.

“I’m very competitive,” he admitted, and is at times envious of the well-resourced bands where students can afford private lessons and well-funded booster clubs make a band director’s every dream come true. But he says his wife, also a teacher, reminds him: “You wouldn’t do well in one of those places where the kids don’t need you. What is a trophy going to do for you?”

It’s great to make beautiful music, sure, he said, but the real reason he’s remained in his role is to see students grow as people, as a team. In sharp contrast to the isolation of the pandemic, he said, band is about more than just music — it’s about being part of something bigger than yourself, caring for others and being cared for, and believing in others and being believed in. It’s also about finding a connection with people you might not otherwise spend time with.

“I think that’s what’s going to turn this pandemic mentality around for the people who are not having a positive experience right now,” Salazar said, finding more spaces to forge new connections.

Ain’t No Mountain High Enough

Even before the pandemic, Salazar knew camaraderie among the band was the reason some of his students showed up to school, the reason they kept their grades up, so they could stay eligible. In March 2020, that bond became a lifeline.

When schools closed and students were disappearing by the thousands, Salazar had flute-players tracking down flute-players and trumpet-players tracking down trumpet-players. He tracked down every single one. But making contact once didn’t guarantee a student’s situation was stable. One student became homeless in the early months of the pandemic, and it took a band-wide effort to keep in contact with them.

Like many, he hoped the pandemic would pass, and kids would be back in formation by marching season. It was not to be, of course. San Antonio ISD brought back only 20 percent of students in September 2020. More and more trickled in throughout the year, but none without scars.

“Their communication skills regressed quite a bit. They forgot how to reach out and ask for help,” he said, adding it’s up to him and his assistant directors to offer it.

The kids in the band call him their “Band Dad,” he said. “The first time I heard it, it was very odd for me. Now it’s a normal thing.”

As someone who had involved and supportive parents whom he credits with much of his success, being a strong “Band Dad” isn’t a responsibility he takes lightly. He knows other teachers who feel this too, like surrogate parents, whose main job isn’t conveying information or handing out grades but being a consistent, supportive presence.

Lean On Me

While Salazar’s expertise uniquely qualifies him to be a band director, he’s just one of many adults who can take the time to listen, encourage, and help connect a kid to the help they need. That’s the part of his job he takes more seriously than making sure the horns are on cue and the winds are in tune.

Sometimes Salazar says he just listens. The students trust their band family, but sometimes he has to convince them it’s time to bring a counselor or social worker into the conversation. He said some of his students have seen family members get sick and die. They’ve watched their parents go from stable working class incomes to wondering where next week’s groceries would come from.

In the depths of the pandemic, he said students couldn’t worry about mastering marching formations or concert pieces, because they were worried about supporting their families, caring for siblings, and keeping up with classwork, he said. Like the virus, those concerns haven’t evaporated entirely. San Antonio ISD only allowed remote learning in a few circumstances at the start of the 2021-22 school year, but a couple of the kids from the band took it.

“They went through so much at home, it’s hard to leave because they have so much to take care of,” Salazar said.

His compassion and care for the kids is bottomless, it seems, but he’s a true believer in the power of a good routine. Even when the entire band was remote, he conducted regular practice, as a way of creating regularity and normalcy when days, nights, weeks, and months were blending together.

From the earliest days of the pandemic, Salazar felt it was essential to reach every kid, every day. “I want it to be as normal as possible,” he said back in May 2020, “There are kids who are freaking out. So I want to be that consistency in their life if that’s what they need.”

Even though other teachers only required contact once per week in the early days, he insisted on daily check-ins. “A lot of teachers don’t understand how important the relationships are,” he said in 2020, during the height of the crisis.

He also believes band can now play a key role in rebuilding the social and emotional skills kids have lost. He thinks back to his own band directors in high school, who emphasized teamwork and conscientiousness just as much as trumpet skills.

Whereas some activities and sports tolerate selfishness and arrogance from superstars, that’s not how Salazar learned to train the band. ”They encouraged me not only to be a good musician but to be a good person,” Salazar said.

“They’d say, ‘you’re a good player, you know, but you can’t be a jerk.’”

We Are Family

For those who are now back at school in person, the majority of the band, Salazar expects hard work. He drills them on the fundamentals, he connects the effort they put in at band practice to the character they will need to succeed in the future. But the support and acceptance he gives in return is just as committed — he’s all in. “There’s days when I feel like I don’t make an impact at all, but that’s not true,” he said. He knows band is making a difference, because the kids prioritize it. Given the crushing stress of the pandemic, he said, when kids are showing up for 6:45am band practice, he knows they see the value in what they are getting.

“We’re here all the time,” said flute-player Victoria Martinez, “This is my family.”

Martinez is a junior and a drum major. While her freshman year was cut short by the pandemic, marching season in the fall and concert season in the winter had given her a taste of what it feels like to win, and a vision of the triumphs that awaited in her years as an upperclassman.

Now, her perspective is different, she said. Returning to in person school at the end of last year, spring 2021, she could see the toll of the pandemic on her peers, many of whom felt disconnected. Those who have band have somewhere to reestablish that connection.

“My freshman year success was about trophies,” Martinez said. “My junior year it’s about giving it all to the band.”

Giving their all doesn’t mean perfection. It can’t. The band is inexperienced. Practicing at home in apartments or full houses was not an option for some. Parents were working, siblings were studying. It wasn’t the right environment to pick up a trumpet.

ABC

To bring back the music, Salazar said, he’s got to do it note by note, and he needs space to do that.

“We’re expected to come back 100%,” said Salazar, referring to statewide reinstatements of academic testing and band competitions. “It’s like we’re pre-COVID again, and that’s not realistic. They want to call it a rebuilding year, but it’s not a rebuilding year if we’re not able to go back and work on these fundamental skills.”

This is the kind of basic back-and-forth that takes up time. Salazar reviews breathing and posture. Basics. It’s tedious, but the kids are up for it. Band President Isaiah Vigil urges them on, reminds them to focus.

Vigil is only a sophomore, and this is his first year with a full varsity band, but as one of the few who were in school in person all year last year, he’s actually one of the more well-rehearsed. Being the president, as a sophomore, he said, is, “Weird…really weird.”

But he likes it. Band teaches responsibility, determination, and respect, he said. Getting it right, practicing, showing up — even when motivation is lacking, those are things the band members do for each other. That’s the thing about band, the members said: No one succeeds or fails alone. If a trumpet wants to sound good, they need the other trumpets to be on cue too. It works the other way too, even when individual members might be tempted to slack off, have an “off day,” they still don’t want to let the band down.

“They really care about each other a lot,” Vigil said of his bandmates.

Better Days

Salazar knows one of the main contributions of a band program is motivation and connection it provides. It’s why some kids come to school, he said. Students have to be academically eligible to perform, and pre-pandemic, that kept the kids on their toes.

Now, he said, no matter how hard they work, eligibility has been a struggle.

Even with about 70 kids enrolled in band, Salazar went through most of marching season with about half that on the field. It’s difficult to prepare for competitions with so many students at risk of sitting out.

But he’s also seeing growth. At the beginning of the year, he said, it was difficult to get through the first four measures of a piece, basically the first line. At a competition a few months later they earned a second tier recognition at a competition. Salazar celebrated it as much as he had cheered the top marks the band had gotten at that same competition in previous years. “The growth was there.”

He posted the win on social media, and band directors and composers around the country celebrated with him.

Bittersweet Symphony

Jose Pulliza hadn’t imagined quite so much growth in his senior year. He wants to be an engineer, so he pictured himself playing his baritone, having a blast with his friends while they earned high marks and trophies.

“It’s nothing like I would have thought,” Pulliza said, reflecting on the difference between his freshmen and senior year. “A lot changed — I grew.”

The pandemic struck at the end of Pulliza’s sophomore year, just before the band was set to perform in San Antonio’s lively parade season. His junior year would be spent entirely at home, as his parents weren’t willing to take the risk of sending him back to school in person. He didn’t march in half-time shows or perform from the stands as the air turned cold during football season of his junior year.

“A year and half really threw me off,” Pulliza said. “It was like being a freshman again.”

He quickly got back on top of his academics — he’s been accepted at the University of Texas at San Antonio — but when it came to band, rebuilding meant more than just polishing his own skills on the baritone.

Pulliza may have been rusty, but he was one of the only members of the band who had actually completed at least one full year. Salazar would need him in leadership.

Pulliza auditioned for drum major, successfully, and he’s been surprised how he’s taken to the role. The responsibility bonded him to the band, helped him settle back into a community.

“People don’t understand how good band is for an individual,” he said. He’s focused on growing as a person, and that’s the message he passes on to his bandmates: success is measured by how you show up, not what accolades you get.

“We just give it our all. We don’t worry about the rewards,” Pulliza said.

One Love

Salazar knows the slim odds that few, if any, of the Mighty Owls will go on to musical professions. But what they are getting from band can still carry over into their future. Passion, caring for each other, hard work, commitment — these are themes in Salazar’s lectures to the band, which he admits are more frequent than they used to be as he focuses on social and emotional health.

“You make them a winner by being there for them, supporting them, and by making this a safe space where they can express themselves.”

Whether it’s the notes on the page, or the melody in their laughter, or the harmony as they work together — that’s what brings the music back.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to both the Weave Project and The 74.

Lead Image: San Antonio high school band leader Alejandro Jaime Salazar (Bekah McNeel)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter