$700B: That’s How Much It Will Cost to Fix Pandemic Learning Loss, Study Says

The researchers also call the lack of transparency into district spending a ‘policy failure’

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Schools have received almost $190 billion for pandemic recovery, but that falls far short of the $700 billion it will take to erase the damage to learning caused by COVID, according to a new study.

And the way the government has distributed the funds — through a formula that targets high-poverty schools — left some communities hit hard by the pandemic with insufficient funding to offset learning declines, wrote Kenneth Shores of the University of Delaware and Matthew Steinberg of George Mason University in Virginia in a paper released Tuesday by the American Educational Research Association.

The researchers push for greater accountability, calling a lack of reporting on how districts are using the funds a “policy failure.” When officials learned which districts participated in remote learning longer, they could have made adjustments, Steinberg said.

“There weren’t efforts in real time … to update the distribution of this aid in ways that would try to maximize its reach to the students and communities that would need it the most,” he said.

In order to build public trust, they recommend that the U.S. Department of Education at least collect data on how a representative sample of districts is allocating the funds.

National test scores set for release later this month are expected to further drive home the impact of school closures on students’ academic progress and spark more debate about whether districts are making wise choices with the unprecedented windfall. The AERA report echoes growing demands from parents and policymakers for greater transparency from districts. Republicans in Congress have asked the department for “insight into how schools are using federal dollars to help America’s students catch up,” and parent groups are seeking training in school finance to track the money. The researchers recommend that officials add incentives to get districts to prioritize academic interventions over projects “such as athletic fields.”

The most recent round of funding, the American Rescue Plan, requires districts to spend a minimum of 20% of their funds to address learning loss.

“But nobody had to stop there,” said Heather Tolley-Bauer, co-founder of Watching the Funds-Cobb, a parent-led group monitoring spending in the Cobb County School District, north of Atlanta. The organization is among those that have received a grant from the National Parents Union to track the funds. “When we look at the things they could have spent the money on and the things they did spend the money on, it’s frustrating.”

Her leading example is the $9.7 million the district spent on “Iggy” hand-rinsing machines that dispense a mixture of water and ozone. The company’s website points to studies that say the machines kill COVID, but some experts disagree and others say there’s not yet enough evidence. But even if the technology is effective at killing the virus, the devices at some schools are inaccessible, with plastic over the openings, Tolley-Bauer said. (A spokesperson for 30e Scientific, the company that makes the machines, explained that some of them have experienced “vandalism by unknown individuals.”)

She understands the district was “in a hot hurry” to address the crisis, but said parents feel excluded from funding decisions.

“I’m not surprised that the federal government didn’t put a lot of parameters around [the money],” she said. “It would help if the schools would …make very strategic decisions that would impact students positively for years to come.”

Some districts have participated in “halftime reviews” to assess spending patterns, said Jonathan Travers, managing partner at Education Resource Strategies, a nonprofit that helps districts resolve budget challenges. In some cases, districts are waiting two to three months for approval of any changes to their spending plans. Districts were able to spend the money quicker on bulk purchases and HVAC upgrades, while tutoring and other student services have taken longer to implement, he said.

Phyllis Jordan, associate director of FutureEd, a Georgetown University think tank that has been tracking the spending, argued that the department has held districts accountable by requiring them to submit plans for the third round of funds.

“There is a level of oversight that you haven’t had before,” she said. “You at least have to articulate how you plan to spend it.”

And the department recently proposed that all states participate in a school-level finance survey that previously was optional. While it won’t focus just on COVID funds, that spending will be included.

Impact on Black students

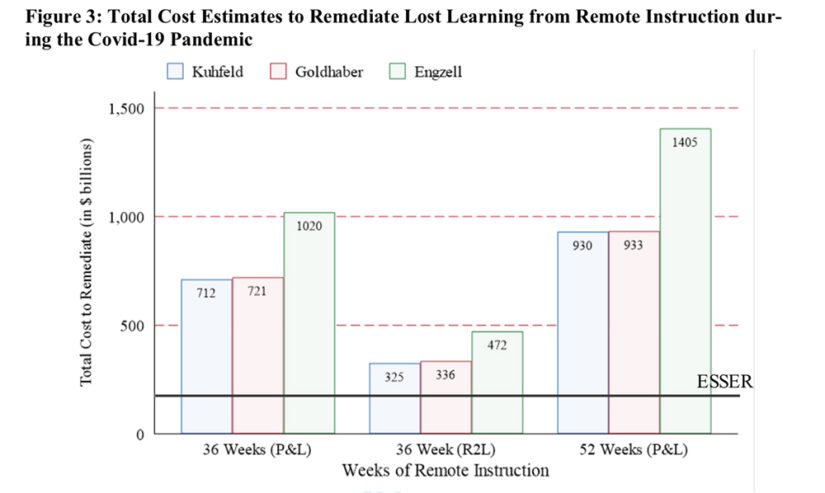

To reach the $700 billion estimate, researchers drew from multiple data sources and existing studies. One was a May report that used assessment data to pinpoint how much of a district’s budget would need to be replaced to make up for missed instruction. In high-poverty districts that were in remote learning for much of the 2020-21 school year, it would be over 40% of their budget.

The researchers on the earlier study, led by Dan Goldhaber of the Center for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research and Thomas Kane of Harvard University, concluded districts would need to spend all of their relief funds to address learning loss, not just 20%.

But Shores and Steinberg think that estimate could be too low because it might not account for learning loss among students that weren’t tested and it doesn’t reflect how families and other “non-school inputs” contribute to student achievement. Previous research, Steinberg said, shows that student performance depends considerably on what is “happening outside of school.”

Their estimates range from a low of $325 billion to make up for missed instruction to a high of $930 billion, with $700 billion roughly in the middle.

Goldhaber said their estimates could be too high, but he noted that either way, the education system has never faced a challenge like this.

“We’re trying to do across the country what has only been done at a small scale,” he said.

Shores and Steinberg also draw attention to the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on Black and Hispanic students, regardless of whether they come from low-income families.

The Education Department’s survey of schools, for example, showed that while the vast majority were open by the end of the 2020-21 school year, the rate of Black and Hispanic students attending full, in-person learning still fell at least 20 percentage points below that of white students. Asian students were the least likely to attend in-person.

Additionally, a report released last year from researchers at Teachers College, Columbia University, said the racial unrest that broke out during the first summer of the pandemic contributed to higher levels of trauma among Black students and families and that schools were “ill-equipped” to support them.

Distributing the funds through the existing Title I formula, which some argue is distributed inequitably across the country, resulted in less funding for districts where the disruption to learning may still have been extensive, Shores and Steinberg wrote.

But Goldhaber cautioned that “it’s easy to be critical retrospectively. When you’re trying to get money out the door quickly, it’s reasonable to use existing vehicles.”

Shores and Steinberg compare COVID relief packages with the federal stimulus package passed to combat the effects of the Great Recession. There’s “not a single study,” they wrote, that demonstrates the impact of that 2009 stimulus package on student learning.

Shores said he’s been disappointed by the “lack of creativity” in directing COVID relief funds. But it’s not too late to change course, particularly when it comes to spending money from the American Rescue Plan, they said.

With roughly a quarter of the funds spent, Steinberg said there’s still time to redirect the money toward tutoring or other interventions that “seem to have potentially positive returns.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)