Williams: The Country Can’t Pretend Its Way Around Flattening the Curve — Especially If We Want to Reopen Schools Soon

Life comes at you fast in 2020. On July 8, the Trump administration waded into the debate over school reopening, threatening to pull federal funding from communities that chose not to reopen in-person schooling in the fall. By July 14, a poll from Axios-Ipsos showed that large majorities of Americans weren’t convinced that it’s safe to send their kids back to schools in person this fall. Then some of the country’s largest school districts came to the same conclusion: Los Angeles and San Diego (and other major school districts) announced last week that their schools would begin the 2020-21 school year online.

Against this backdrop, White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany took to the podium on July 16 to clarify the administration’s case for reopening schools. “The science should not stand in the way of this,” she said. McEnany continued, paraphrasing the Hoover Institution’s Dr. Scott Atlas: “Of course we can do it, everyone else in the Western world, our peer nations, are doing it. We are the outlier here. The science is very clear on this.”

So much for clarity. It is true that the United States is an outlier right now in the developed world; other countries have pulled out of their pandemic-driven recessions, restarted their professional sports leagues and — indeed — reopened their schools.

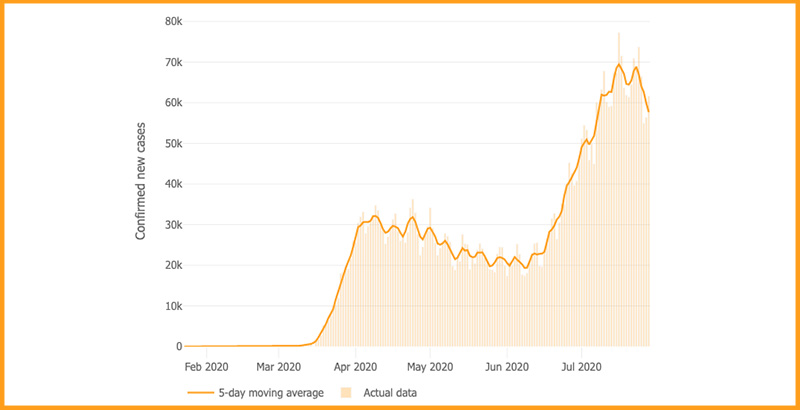

It is also true that the United States remains an outlier in its utter failure to contain and control the pandemic. This week, the country’s dramatic wave of new coronavirus cases continued to grow. The day that McEnany demanded that schools reopen, the U.S. (population around 330 million) reported more than 75,000 new cases of the virus. For comparison, Germany (population just over 80 million) has registered around 200,000 cases — in total.

Something seems to be awry in our response to the coronavirus. If the science is very clear on reopening, how could it simultaneously risk standing in the way of schools reopening?

Fortunately, earlier this month, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) released a new report on the topic, Reopening Schools During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Prioritizing Health, Equity, and Communities.

Contra McEnany, the researchers consistently warn that data on COVID-19 risks are lacking, particularly for children with other health conditions, like asthma. “Clear guidelines on which children are at sufficiently high risk to require alternative educational modalities is not possible,” the authors write. Researchers also found that “there is insufficient evidence to determine how contagious children and youth are or how likely they are to contract the virus.” Indeed, since the report’s release, a new study from South Korea has found some evidence of higher rates of COVID-19 transmission in children above the age of 10. Research on schools’ role in spreading the virus “has produced mixed results.” Further, airborne transmission of the virus remains an open question, particularly in schools with poor ventilation. Finally, the researchers were unable to come to a consensus on what efforts schools should undertake to stop the spread of the virus when schools reopen, though they urged schools to “prioritize” the wearing of masks, handwashing, social distancing and avoiding large gatherings.

This all seems about right. As I’ve written before, the combination of unchecked spread of the coronavirus pandemic and uncertainty about the specific risks to children and teachers make it extremely difficult to imagine a future where schools can safely open for in-person instruction this fall. In Israel, schools appear to have played a significant role in sparking and amplifying a second wave of the pandemic. With increased testing, Australian leaders have found greater evidence that children may, in fact, transmit the virus more than previously thought. Health officials in Florida are warning that children who get the virus — even if they don’t display symptoms — appear to have persistent lung damage.

Worse yet, there’s significant evidence (including in the report) that the pandemic’s health impacts are already being unequally borne across diverse groups of Americans. Communities of color are significantly more likely to contract the virus — and die from it. There are similar patterns for children as well. A recent report from UnidosUS found that nearly 54 percent of U.S. children who have contracted the coronavirus are Latino. That’s roughly double the share of U.S. children who are Latino (25 percent). Presumably this trend would only increase if we reopened schools soon, with the pandemic largely unchecked and a likely second wave coming in the fall.

So yes, the United States remains an outlier in delaying the return to normal schooling — but that’s largely because we’re orders of magnitude away from reducing our numbers of new coronavirus cases to the levels of other countries who made that move.

And yet, with so much uncertainty, with the pandemic escalating, with only a few weeks until the school year starts, the NASEM report still concludes that “districts should prioritize reopening with an emphasis on providing full-time, in-person instruction in grades K-5 and for students with special needs.”

Wait, what? Despite all of the uncertainty about transmission and mitigation, the researchers still looked at existing health data and decided that a return to in-person schooling makes sense?

Just as with the American Academy of Pediatrics report on school reopening last month, much of the coverage of the new NASEM report has focused on this one line, instead of all the warnings that precede it in the report. It’s as if these reports are saying the responsible, discouraging stuff quietly — and the risky stuff out loud.

Yes, there are real considerations in addition to concerns about students’, families’ and teachers’ health. The extended loss of access to in-person public schooling is bad for kids and will contribute to significant lost learning, particularly for historically marginalized communities. There’s little encouraging research on remote learning. It doesn’t appear to work very well, even under the best of circumstances. It doesn’t appear to have worked especially well in most settings during the COVID-19 outbreak. And many children — including mine — are weary of the prolonged isolation of social distancing. As a working parent, I am [all the expletives] wiped.

But none of that means that we can just shrug away the public health risks of reopening schools. The country’s response to the pandemic has been so loose, piecemeal and ineffective that we seem unlikely to meet the public health conditions to reopen schools safely in the fall.

To be sure, the report acknowledges that “the reality of the current public health situation [means] districts are likely to use a blend of in-person and distance learning.” It also sets baseline expectations for schools hoping to reopen in person this fall. It recommends that local leaders provide all staff with surgical masks and “supplies for effective hand hygiene.”

Polls suggest that educators are wary of returning to school until the pandemic is better contained. Three out of 10 U.S. teachers are over 50 — that is, in an elevated risk group for the virus. The report warns that many may retire rather than take the risk of returning to in-person education, and it recommends that “any plans for reopening will need to address these concerns.” How? That’s not spelled out.

In essence, whether or not education leaders “prioritize” reopening in-person instruction this fall, they’ll need significant new public investments to lower the health risks. Bulk purchases of masks and soap are just the beginning. Districts will need to run more bus routes to get kids to campus safely, because socially distant bus rides can’t carry as many kids. Schools may need to overhaul costly air ventilation and filtration systems, install plexiglass barriers, modify classrooms and renovate other pieces of their physical infrastructure. Reduced class sizes to social distance on campus will also increase costs.

All of that costs money. But schools in most states and communities are facing likely cuts as local and state revenues drop because of the coronavirus. And notwithstanding the uncertainty that runs through the NASEM report, on this point it is crystalline. Without “substantial financial support from the federal government and state governments, it is likely that the communities most impacted by COVID-19 will see even worse health outcomes in the wake of reopening schools” [emphasis added].

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)