Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

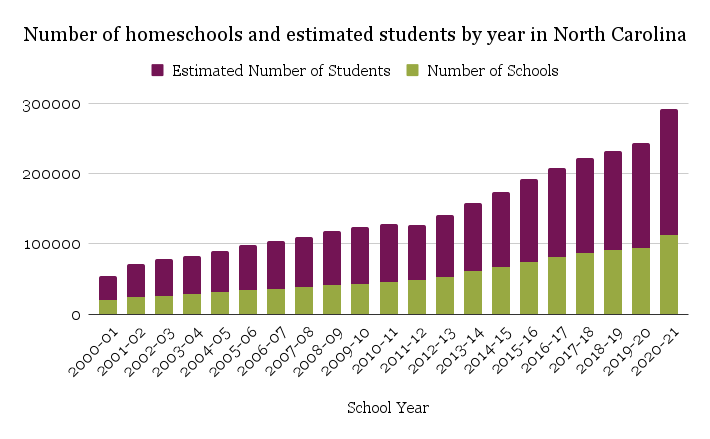

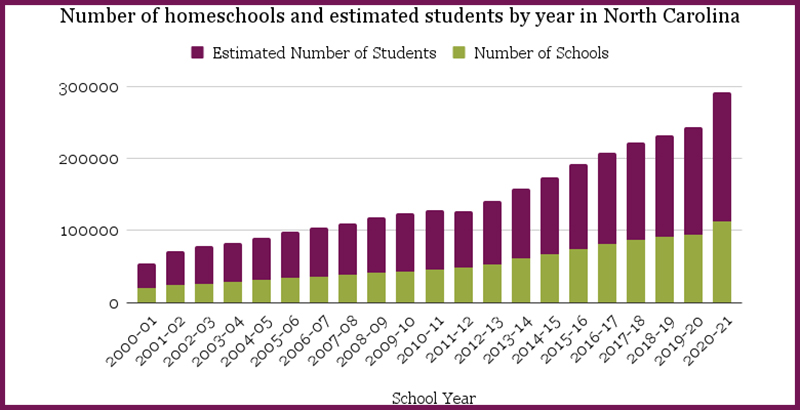

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a fairly dramatic increase in the number of home schools and home-schooled students in North Carolina.

The number of home schools went from 94,863 in the 2019-20 school year to 112,614 this year — an 18.7% increase. In terms of students, the state estimates 149,173 in 2019-20 and 179,900 this year. Those numbers aren’t exact because the state doesn’t necessarily receive accurate information, or any information, on the number of students in a home school. But using the estimate, the change in students from last year to this one was almost 21%. (For more information about why the enrollment number is an estimate, or how the estimate is determined, see below.)

Between 2016 and 2021, the number of home schools has grown by 39% and the number of students has grown by 41%.

Click here for the data, including numbers by county.

What is the reason for this growth, and what does it mean for education in North Carolina?

Delving deeper

The public schools’ share of students has been dropping for years. Every year from 2016-17 to 2019-20 (the most recent year for which data are available on the state Department of Public Instruction’s Statistical Profile), the number of students served has been going down. In 2016-17, enrollment was 1,486,448. In 2019-20, it was 1,458,814.

Meanwhile, in the second month of the 2020-21 school year, there were 63,000 fewer students than in the previous year. That’s a 4.4% loss, according to Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography at the Carolina Population Center at UNC-Chapel Hill.

The annual charter school report for this year put enrollment at such schools at 126,165 as of Oct. 1, 2020. The same report puts the number in 2019-20 at “over 117,000.” Also, the number of charter schools in the state has essentially doubled since the 100-school cap on charters was lifted in 2011.

Charter schools are also public schools, but they are not run by school districts. Instead, for-profit or nonprofit organizations operate them. These schools get certain flexibilities from the rules and requirements that apply to traditional public schools.

The state Division of Non-Public Education puts enrollment in private schools at 107,341 for this school year, an increase from 103,959 the year before. Private schools also generally see enrollment growth year after year.

With the 179,900 estimate of home school enrollment this school year, home schools are now the second most popular choice for education in the state after traditional public schools.

The number of home schools from 2016-17 to 2017-18 went from 80,973 to 86,753, a 7% increase. Enrollment went from 127,847 to 135,749, a roughly 6% increase.

From 2017-18 to 2018-19, the number of home schools went up 3,935 and enrollment went up 6,288. The percent increase in both cases is about 4.5%.

From 2018-19 to 2019-20, the number of home schools increased by 4,175 and enrollment went up 7,136. That’s a 4.6% and 5% increase, respectively.

Here is a chart that illustrates the growth since the 2000-01 school year:

One superintendent’s experience

Surry County Superintendent Travis Reeves said that he and other superintendents around the state have noticed the trend of students leaving traditional public schools for home schools.

“I think really at the end of the day, school systems need to ask themselves why, and how do we look at that market,” he said.

For their part, Reeves said Surry County Schools wanted to see why families were choosing home schools and what they were looking for in an education. In his district, staff got in touch with home school families and even went to home school fairs.

In February 2020, before the pandemic, Reeves’ local board of education changed some of their policies so that the district could open home school partnerships.

So, for instance, home-schooled students in the Surry area can now come to Surry County Schools and take some classes. They become dual-enrolled in their home school and the school district.

“We think once people come into the door, get to know our teachers, get to know our principals, they are going to really like what we have to offer,” he said.

Check out the district’s page for home-schooled students here.

In addition, during the pandemic, the district opened an online magnet school. Reeves said it’s distinct from the virtual academies that many districts had to open during the pandemic. The Surry Online Magnet School, which started in August, has its own dedicated principals and teachers. Reeves called it a “true online school.” It had its first graduation in May.

When the school opened, Reeves said there was a lot of interest from home-schooled students, and many of them joined the school.

“If we weren’t offering that choice, then we potentially would have 210 more students who would be choosing home school options,” he said.

But, he said, many also left to go back to home school. He said in many cases, they were trying to avoid requirements related to testing, accountability, and attendance.

“Some families said it was just too much work,” he said.

Reeves recognizes the growth in the school choice movement around the state. But he said traditional public schools also offer choices to students and families, be they magnet schools, online schools, or other options.

‘We’re trying to offer families choice because we believe in public education that the work we’re doing is good and it’s really important,” he said.

Reeves also said there is an essential element that traditional public schools bring to students’ lives — the sense of community and belonging that people get when they learn, play, and thrive together. He called that feeling of togetherness and unity the “cornerstone of our democracy.”

“I’m concerned that we’re losing some of that,” he said.

Why is this happening, and what is to come

There is little argument as to why home school numbers jumped so high from last year to this one. But what about the steady growth before the pandemic? And will growth return to a steady state or has the pandemic jump-started something bigger?

Families choose to home school for a variety of reasons: the perception that public and private schools aren’t rigorous enough or don’t have enough resources, the growth of online options and home school communities, because children have disabilities parents don’t believe can be addressed in school, or even just personal and family issues.

Then the pandemic hit. In July 2020, interest in home schools was so strong, that the website where parents can register shut down for almost a week. But will the dramatic increases stick now that COVID-19 is less of a concern?

Terry Stoops, director of the Center for Effective Education at the right-leaning John Locke Foundation, said he thinks it will.

“I think a lot of the families that chose to home school during the pandemic will find that it is not only something that their family can do but also something that their family likes,” he said.

Furthermore, Stoops said the best advertisement for home schooling is people who do it talking about it with people who don’t.

Matt Ellinwood, director of the Education and Law project at the left-leaning NC Justice Center, said that he thinks some of the new home school families will stick with it in the short term, but longer term he doesn’t think the increase seen during the pandemic is permanent.

“The pandemic is not over in a lot of people’s eyes either,” he said, adding that the fact that children under 12 years of age can’t be vaccinated yet doesn’t help.

Ellinwood said he thinks that home schools may get a little extra bump in permanent enrollment, but nothing as dramatic as the jump seen during the pandemic.

He also said he’s concerned about the increase in home schools this year because much of it came from families who didn’t necessarily plan to teach their children at home and thus didn’t set up an adequate educational experience for their children.

“It is a lot,” he said. “There’s all kinds of lesson plans and things that need to happen.”

“Parents who home school their children have free rein to teach them what they would like in North Carolina, although the state does require that home school students take annual standardized tests in English, grammar, reading, spelling, and mathematics,” wrote Molly Osborne, director of news and policy for EducationNC, in this 2017 article. “Parents are not required to submit the results or any evidence of compliance with the testing requirement. However, they must keep the test results for at least one year in case the state wishes to inspect them.”

Ellinwood suggested that stakeholders — including home school parents, education leaders, and legislators — should get together and find a way to make sure that home-schooled students are actually getting an education without taking away the freedoms their families guard so strongly.

As to whether an increase in home-schooled students is a good or bad thing, Stoops and Ellinwood look at the question from different angles.

Stoops said that arguing over whether public school is superior to home school is missing the point. The point, he said, is to address the needs of children.

“My personal view is that it’s a net positive when a student is successful in schools, and whether that environment is in a home or in a public school classroom is irrelevant to me. And it should be irrelevant to policymakers,” he said.

Ellinwood said, however, that the more families move to home schools, the fewer people have “skin in the game” when it comes to public education.

“The vast majority of people are educated in the public school system,” he said. “They want to ensure that we have the necessary programs … in those schools, but if we have more and more people who aren’t attending those schools, it takes away some of the public will.”

This is the language used by the state Division of Non-Public Education to explain how student estimates are determined:

“Student enrollment estimates are based on an algorithm where values for non- reporting schools and schools with reported numbers that are not possible (such as 10 students in one grade, etc.) are imputed based upon the average students per school obtained from all remaining schools within a county that reported student numbers. Similarly, enrollment by grade was derived by assuming the same grade distribution for non-reporting schools as the remaining schools in the county.”

EducationNC’s Osborne explained further in the 2017 article:

“Along with 42 other states, North Carolina requires home schools to register with the Division of Non-Public Education (DNPE). Parents must provide the name and address of the school and the school’s owner and chief administrator, but they do not have to report the names, ages, number of home-schooled students, or any other information (which is why the numbers for home-schooled students in the state are estimates, not actual counts).”

This article originally appeared at EdNC.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)