Youth Vaccination Rates Plummet, Reigniting Debates Over Masks in School

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

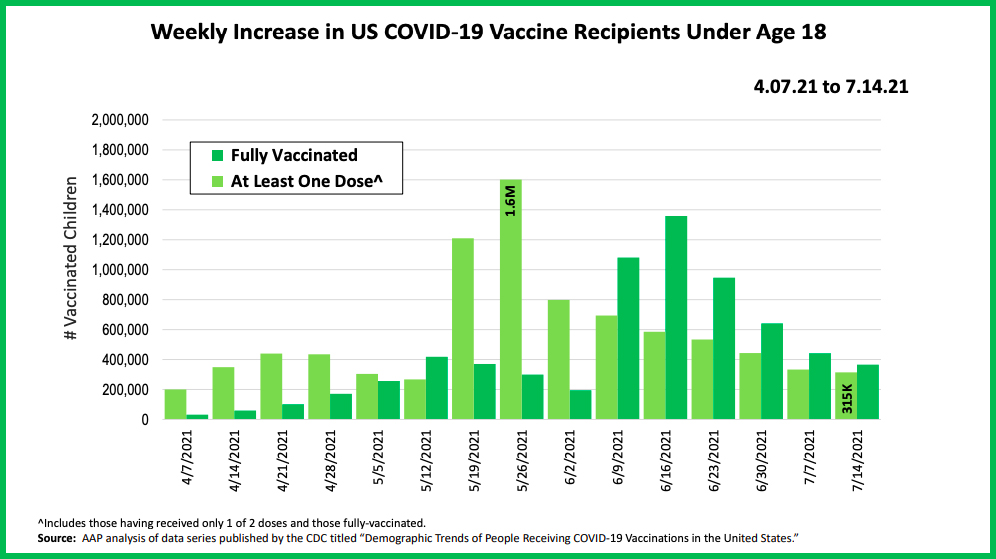

When teens and adolescents first became eligible for COVID-19 vaccinations in mid-May, demand for shots was like a spigot turned on full blast.

Now, the once-steady stream has slowed to a feeble drip.

Last week, only 315,000 youth rolled up their sleeves for immunizations, down from a peak of 1.6 million in late May, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics review of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

“[T]he rate of youth vaccinations has slowed in recent weeks,” Jennifer Shu, a pediatrician and spokesperson for the AAP, wrote in a message to The 74. That trend poses a grave risk, she says.

“Vaccinating teens and adolescents is their best protection against severe COVID illness. Also, having higher vaccination rates overall can reduce the potential of variants — which may be more contagious — to develop and spread in schools and communities.”

As of July 14, some 6.8 million Americans under the age of 18 were fully vaccinated, representing 38 percent of 16- to 17-year-olds and 25 percent of 12- to 15-year-olds. Another 2 million teens and adolescents had received a single dose.

The slowdown in youth immunization tracks with what Nicolette Carrion, who worked in May and June as a youth vaccine ambassador in her hometown of Nassau County, New York, has heard in conversations with peers about the shot.

When youth first became eligible for vaccinations, many were eager to get immunized so that they could enjoy events like prom, graduation and summer hangouts with friends, she said. But now the social pressure has eased off.

“At this point, everyone (who’s) vaccinated, they’ve been done with it, and they don’t want to talk about vaccines anymore. And everyone unvaccinated probably wants to avoid that conversation,” Carrion, a rising sophomore at Georgetown University, told The 74.

Low youth vaccination rates spurred the AAP on Monday to recommend universal masking for students and staff as classrooms reopen this fall.

“There isn’t a uniform way to determine who and how many individuals within a school are vaccinated … and therefore [it’s] difficult to enforce masking simply for unvaccinated people,” explained Shu. “So universal masking is the best way to be consistent in protecting everyone.”

That stance clashes with guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which holds that mask-wearing in school is only recommended for individuals who have not received COVID-19 immunizations. The AAP’s recommendation contributes to mounting pressure on the CDC to revise its school guidelines, according to recent reports.

Nationwide, eight states bar school districts from requiring face coverings in the classroom, while nine states mandate that all schools enforce universal masking, according to Burbio’s mask tracker. Most other states leave the decision up to individual school systems.

Those policies come as experts struggle to understand what exactly is the risk to unvaccinated kids of the new, more contagious Delta variant that has quickly spread across the country.

Last school year, a collection of 130 studies found that schools were not the locus of community spread, and could safely reopen as long as safety measures like ventilation, masking and distancing were in place and infection rates in the surrounding area were not raging.

But in June, experts told The 74 that this summer and fall may mark the “most dangerous” time in the pandemic for unvaccinated individuals and young people due to spread of the Delta variant. In the United Kingdom, a new study found that youth were behind the country’s most recent surge, testing positive for the virus at a rate five times higher than seniors.

Those warning signs should spur officials to revisit school safety policies, says Shu.

“This pandemic is a moving target and we are constantly adapting and adjusting guidelines including those on masking,” she said. “States that currently ban mask mandates could adapt given new information and recommendations.”

But while the most recent COVID mutation is undeniably more infectious than previous strains, it is not necessarily more severe. It spreads rapidly, but there is not evidence that the health outcomes for infected individuals are worse than those who got sick from other versions of the virus — meaning kids’ chance of hospitalization and death remains low.

Earlier this month, FDA officials said that authorization of COVID vaccines for children under 12 is expected to come midwinter.

In the meantime, vaccine requirements at as many as 500 colleges and universities could help encourage older teens to receive their shots. On Monday, a federal judge blocked a challenge to Indiana University’s mandate that students must be immunized before returning to campus.

For younger teens and adolescents, the trick may be to rethink the incentives for vaccination, suggests Carrion. Offering video games as a prize, or tapping influencers to speak up about vaccination could help, she says. Bringing pop star Olivia Rodrigo to the White House last week to speak about the shot alongside President Biden she thinks was a good start.

“That age group is very impressionable,” said Carrion. “It all matters.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)