To Bring Back Struggling Students, Districts Campaign to Convince Parents Schools are Safe

When officials in San Antonio’s largest school district threw open the schoolhouse doors in September, they wanted the most vulnerable students to return first.

Instead, families at schools where more students are white have been eager to send their children back for in person learning. In poor, largely Black and Latino communities hit hardest by the pandemic, parents have been reluctant to take on the risk of in-person instruction, leaving many vulnerable students out of their teachers’ reach.

Now, Northside Independent School District and others across Texas are in an all-out campaign to convince Black and Latino families to send their kids back to in-person classes, leaving school leaders in unfamiliar territory trying to assuage the concerns of wary parents.

“(The pandemic) puts good relationships to the test. It puts trust levels to the test,” said Janis Jordan, Northside ISD deputy superintendent for curriculum and instruction.

Their success has varied from school to school in the city’s largest school district.

To win parents’ trust, Northside has created an exhaustive FAQ and series of videos with Superintendent Brian Woods. Principals are giving campus safety tours showing plexiglass guards and social distancing plans—in person and virtually. Case managers and family specialists make regular home visits, assessing what the family needs to stay connected to school, and to stay stable.

Parents, meanwhile, say districts must understand the new dynamics in each family, including the role that many older children now play — such as tutoring younger siblings. Schools need to be sensitive to the risks the family can afford to take.

“School leaders need to know their communities better,” said Heather Eichling, a parent in neighboring San Antonio ISD, whose family is bicultural. Most of the parents in her school fall into the demographic Northside and others are struggling to reach. “They need to set aside their own value system and listen to their families.”

While these parents value education, she said, they need to know that they don’t have to sacrifice their family’s safety to access it.

Safety Front and Center

At Martin Elementary, a Northside ISD elementary school where only 22 percent of students selected in-person learning at the start of the school year, principal JJ Perez doesn’t want parents to doubt for one second that their students, and families will be safe.

Perez lost his mother to COVID-19, and has been transparent with the community about how seriously he takes the virus. He made a series of videos highlighting the various safety measures the school put in place such as social distancing guides for kids and handwashing breaks, and put them on social media.

Parents say the video explainers have been helpful: They don’t just have to take the school’s word for it.

Parents often tell Kandace Sanchez, Martin Elementary’s Communities in Schools site coordinator, they are doubtful that little kids will keep their masks on, but she’s been able to reassure them that, actually, the kids do a great job.

Sanchez and much of the outreach team at Martin have another advantage — many speak Spanish.

Early in the pandemic, a lot of information was only distributed in English, said Sanchez’s co-coordinator Joanna Hernandez, and the team at Martin had to do more than just translate a couple of fliers into parents’ dominant language. They had to be able to answer questions, walk through tech support, and give parents the reassurance that nothing had been lost in translation.

Each little piece of this complex family engagement puzzle took Martin Elementary one step further, reassured one more family here, two more families there. By the end of October, 44 percent of the students had come back, average for the district.

Home Visits

As a drop-out prevention nonprofit working in 100 schools in San Antonio, usually Communities in Schools would focus on the barriers to academic success. They would figure out why a student was struggling in class, and specifically try to address that issue.

During the pandemic they have broadened their focus, said site coordinator Joanna Hernandez “We started approaching the family as a whole.”

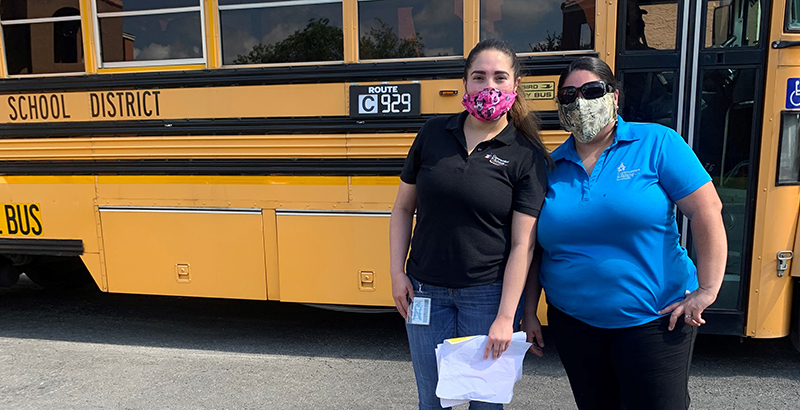

She and Sanchez have been making home visits to drop off learning devices or other school supplies. These visits, which used to be more extraordinary, have become a regular part of their routine.

“We’re playing a bigger role,” she said. “We’re not taking this lightly at all.”

They try their best from a safe distance to quickly assess what else the entire family might need. Across the city Communities in Schools staff has been delivering everything from grocery store gift cards to extra beds and mattresses.

Until a family is stable, they explained, school is one more variable to juggle, whether that means logging in or showing up in person.

At Roosevelt High School, a Title I school in neighboring North East ISD, San Antonio’s second largest district, family specialist Melissa Mendiola is trying to remind families of the support services more easily available within the walls of the school building.

“I’m doing 10-15 home visits a day trying to get kiddos to come back,” Mendiola said.

Once kids get to school, she walks the courtyard, reminding students to pick up meals and weekend food bundles provided by a local nonprofit. She wants word to get out that the benefits of in person attendance are real.

But it’s been a hard sell.

“There’s so many things that you just didn’t expect, that you thought were going to be different,” Mendiola said, “The first nine weeks was a real shocker.”

Family Matters

One child parents might be keeping home: older siblings with an expanded role in the family during the pandemic.

Upper elementary, middle school, and high school students are in charge of helping their younger siblings log on, Hernandez has observed.

Bringing back just an older child leaves a hole in the family’s daily schedule and ability to manage the virtual learning technology. So a struggling fifth grader might have to stay home because they are critical to keeping a first grade sibling from completely disengaging.

This led school leaders to prioritize bringing back sibling groups, Hernandez explained.

For many parents, though, family first means prioritizing the health of vulnerable members of the household. Vulnerable family members, including grandparents. Asking parents to choose school, with its inherent risk, and to distance from family, Eichling said, is going to be a losing battle.

During the pandemic, Eichling has felt the influences of both white professional culture, where school and work prioritized, and Latino working class culture. She understands the strong familial and community ties and sense of obligation in Latino families which make social distancing difficult, even unrealistic.

While they value education, Eichling said, generations of Black and Latino families have not experienced the school system as reliable. “The education system doesn’t value them. It’s never valued them.They know all this.”

When prioritizing academics means risking health or separating from family, it sounds to them like a bad bet.

In times of crisis, communities will cling to the things that have helped them weather the storms of the past. “They are not afraid to struggle,” she said, “They are afraid to lose the one thing they rely on: health and family.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)