Gordon Parks Showed America the Rage Behind Decades of Racial Unrest. On Thursday, Minneapolis Rioters Burned the School Named for Him

On the third night of the anarchy that is reducing my city to cinders, someone started a fire at Gordon Parks High School. It was one of hundreds of fires that have accompanied protests over the killing of a black man by Minneapolis police officers. The school fire did not make national headlines — no surprise, given that the main event the night that building was torched was the burning of the police department’s Third Precinct and several beloved and historic surrounding blocks.

Gordon Parks is located in St. Paul, in normal times a quick drive east from the locus of the protests that followed a Third Precinct officer’s lethal decision to use his knee and body weight to crush the neck of George Floyd. Part of St. Paul Public Schools, it’s an alternative learning center serving some 170 students who have been failed by the system.

To see it on fire made my heart lurch. The school is named after a black photographer, author and filmmaker who, working for Life magazine and other mainstream news outlets from the 1940s until his death in 2006, helped white America literally see the “why” of race riots of decades past. Orphaned and left to the streets, Parks did not attend high school. His work showed the world what the racism and poverty of his childhood meant, documenting the desperation and pain fueling race riots over six decades.

“I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapon against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty,” he famously said. “I could have just as easily picked up a knife or gun, like many of my childhood friends did.”

The high school named after him sits in a symbolic spot. As in many places, the construction of the freeways that traverse Minneapolis and St. Paul displaced tight-knit black communities, effectively creating concrete moats that reinforced the shameful history of redlining, the practice of banning people of color from certain neighborhoods.

Gordon Parks High School sits blocks from Interstate 94, which paved over the heart of the Rondo neighborhood in 1968, forcing out 500 families and devastating their cultural institutions. What was initially called the Saint Paul Area Learning Center first opened in a depressed strip mall. Twelve years ago, when it got a lovely, airy building down the street, a teacher suggested renaming it after Parks.

I desperately want to do what I would do in normal times and just keep typing about the interesting ways its teachers use Parks’s legacy to re-engage students lost to the system. But as I mentioned before, my city is burning, and too many of our kids, watching a white so-called peace officer kill a man who looks like them, are displaced again — this time by a strange brew of peaceful protest and rioting, some of it at the instigation of outsiders who have brought homemade explosives to our neighborhoods.

The night the school was set afire, the police abandoned the precinct house, which was then overrun and quickly set ablaze. For four nights, residents caught up in the destruction could not count on backup from first responders, spread thin. Elected officials warned that we need to band together to watch out for one another while the National Guard and other law enforcement attempt to quell violence and put out fires.

Set aside the confusion about outside terrorism, and what you are seeing on TV is the potent brew that is Minneapolis: prosperous and largely progressive white people who, like me, have Gordon Parks’s works on their bookshelves and coffee tables, and who somehow can’t fathom that the status quo is literally killing the kids who end up at Gordon Parks High School. When the fires are out, we need to address this conflagration.

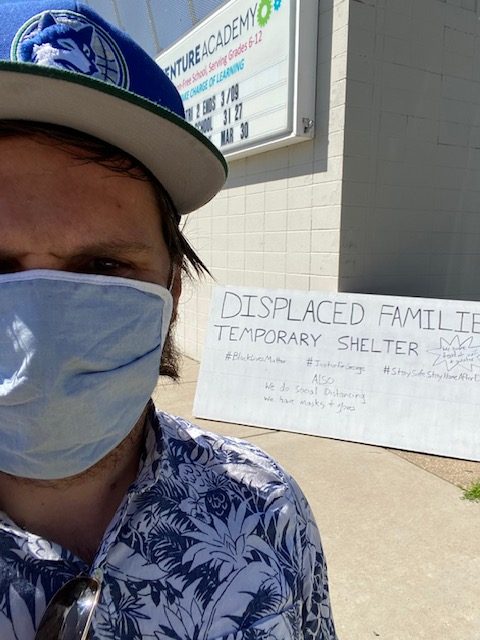

Meanwhile, our schools, already stretched wafer-thin by the need to serve as sources of food, mental health support and human connection in a time of pandemic, have yet again another role to play in supporting their communities. With grocery stores destroyed in neighborhoods that were already close to being food deserts, they have opened to accept and redistribute food, diapers, hygiene supplies and more.

Night four of the unrest was the worst so far, with the governor communicating in the middle of the night that the National Guard was outnumbered. The following morning, the school my daughter is supposed to graduate from in a few days decided to reopen — as a sanctuary. Staff worked tirelessly to contact families to make sure they knew doors were open and there was food, bedding and social distancing if they needed to flee their homes, and to urge the safe expression of rage and grief during daylight and prudence when the sun went down.

Students and staff were displaced but sheltered with relatives. So on Sunday, teachers packed their cars and started visiting their students.

The scenes have been surreal.

One of my daughter’s classmates, Abigail Valtierrez Catalan, describing the destruction of her family’s business, leaving home and keeping her siblings out of earshot during tough adult conversations. Her mother’s voice is the one we have all been hearing on calls home from the school.

A former school board member narrating how he and his neighbors held down his block.

The student body president at Minneapolis’s North High School, which has one of the city’s more complicated and painful racial legacies, thanking his teachers and principal on video on the occasion — unrest notwithstanding — of his graduation.

Our former mayor explaining in plain English why our police do not respect or obey our civilian officials or their thoroughly decent and human chief (ironically known to us by the nickname Rondo) and explicitly owning his failure to reform the department.

A young man determined to have his accomplishment — a high school diploma — photographed against a backdrop of flames.

I live on what we call a transitional block — Minnesota parlance for the streets with not-so-handsome homes on the edge of a wealthy neighborhood. We have not been exempt from the anarchy, but we are not near the epicenter. All weekend, my neighbors and I saw trucks and SUVs without license plates circle our blocks and listened as the governor explained that state police and investigators believed many of these cars were stolen and being used to transport “incendiary devices.”

Saturday night, my neighbors and I watched from our stoops as a convoy of law enforcement vans and trucks, carrying men in tactical gear and accompanied by an ambulance, arranged themselves in a convoy in the parking lot of the garden center across the street. I sat on my front steps until the concrete was no longer warm from the sun, thinking about the symbolism of the fire inside Gordon Parks High School.

The morning brought blue skies, sweet air and a temporary — and illusory — break. The garden center parking lot filled to overflow capacity with shoppers. It’s busy around this time every year, though this spring the confinement of COVID-19 seems only to have fueled the urge for new growth. The perennials being wheeled across the parking lot were lush.

Across town, people were flooding schools with food and supplies. The line to drop off grocery bags at one middle school was, at one point, 14 blocks long. When the school’s lawn was saturated, teachers took to social media to direct people to others down the street. Many grabbed brooms and headed out to start the cleanup of devastated swaths of the city.

So how do we reconcile these two faces of Minneapolis? The one where some people of means will risk a pandemic store run to get diapers to someone whose neighborhood is smoldering, and the one where others take advantage of a 75-degree day to get the day lilies in?

It’s a slender reed, but right now I am clinging to the thought that at Gordon Parks High School, some of our most historically neglected young people are being taught to use Parks’s weapon of choice: the cameras and other storytelling tools that will enable the world beyond Rondo to understand how we got to this moment, this tipping point.

The morning after the fire at the school, Parks’s grandniece, Robin Hickman-Winfield, taped a short message to students that is a more fitting last note than anything I could pen. So I leave you with her vision for the path forward.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)