Is School Choice the Black Choice: A Lack of Student Performance Data and the Need for More Black-Run Charters Focus of Philadelphia Town Hall

Updated, June 3

Philadelphia

Philadelphia has a data problem, and the district’s regression from transparently reporting on student achievement by race and ethnicity is not only a cause for concern but also an intentional move to hide poor performance among black students, panelists said during a discussion on school choice Wednesday night.

“They did that on purpose,” said David Hardy, executive director of Excellent Schools PA. “Because once you start dissecting the data, you saw the real thing. They don’t want those numbers to come out like that.”

Around 150 families and community advocates attended “Is School Choice the Black Choice?” — an education town hall at Mastery Charter School–Shoemaker Campus led by broadcast journalist Roland Martin. The event was the third in a 10-city tour hosted by Martin and The 74. The events aim to engage black families and stakeholders on issues of educational equity, student achievement and parent involvement.

Across Pennsylvania, 31 percent of all third-graders proved proficiency in mathematics on the 2018 Pennsylvania System of School Assessment, the annual statewide assessment. That same year, proficiency among the state’s third-graders in English Language Arts was 44 percent.

In Philadelphia, however, a racial disparity becomes apparent when diving into the performance data, and disproportionately so. In a city where black students are the majority and the white student body hovers around 15 percent, Philadelphia’s white students overwhelmingly outperform their black counterparts. Some 41 percent of the city’s white third-graders were proficient in English in 2018, and 29 percent showed proficiency in third-grade math, while just 25 percent of the city’s black third-graders were ELA-proficient, and only 13 percent exhibited proficiency in math.

And on the 2017 National Assessment for Education Progress, widely referred to as the Nation’s Report Card, Philadelphia’s white fourth-graders outperformed their black peers by 37 points in math — the fourth-widest black-white achievement gap of the country’s urban districts. That figure was 34 points in reading, the 10th-largest gap across urban districts.

“We’re up here as so-called experts on Philadelphia and we couldn’t tell you [the proficiency data] — that’s a problem,” said Sharif El-Mekki, principal of Mastery Charter School–Shoemaker Campus. “Imagine families being bombarded with stuff. If we are transparent and people know about stuff, they get angry.”

Also on the panel were Toya Algarin, a parent advocate and KIPP Philadelphia board member; Christina Grant, chief of charter schools and innovation for the School District of Philadelphia; Bryan Carter, CEO and president of Gesu School; Lenny McAllister, director of Western Pennsylvania Commonwealth Foundation; and Jessica Cunningham Akoto, CEO of KIPP Philadelphia.

“At the current rate of academic performance, it will take African Americans 287 years to catch up,” said Steve Perry, head of schools and founder of Capital Preparatory Schools in New York City and Bridgeport, Connecticut.

“Which is why we can’t get caught up in the silly fight about charters or whatnot,” Martin responded.

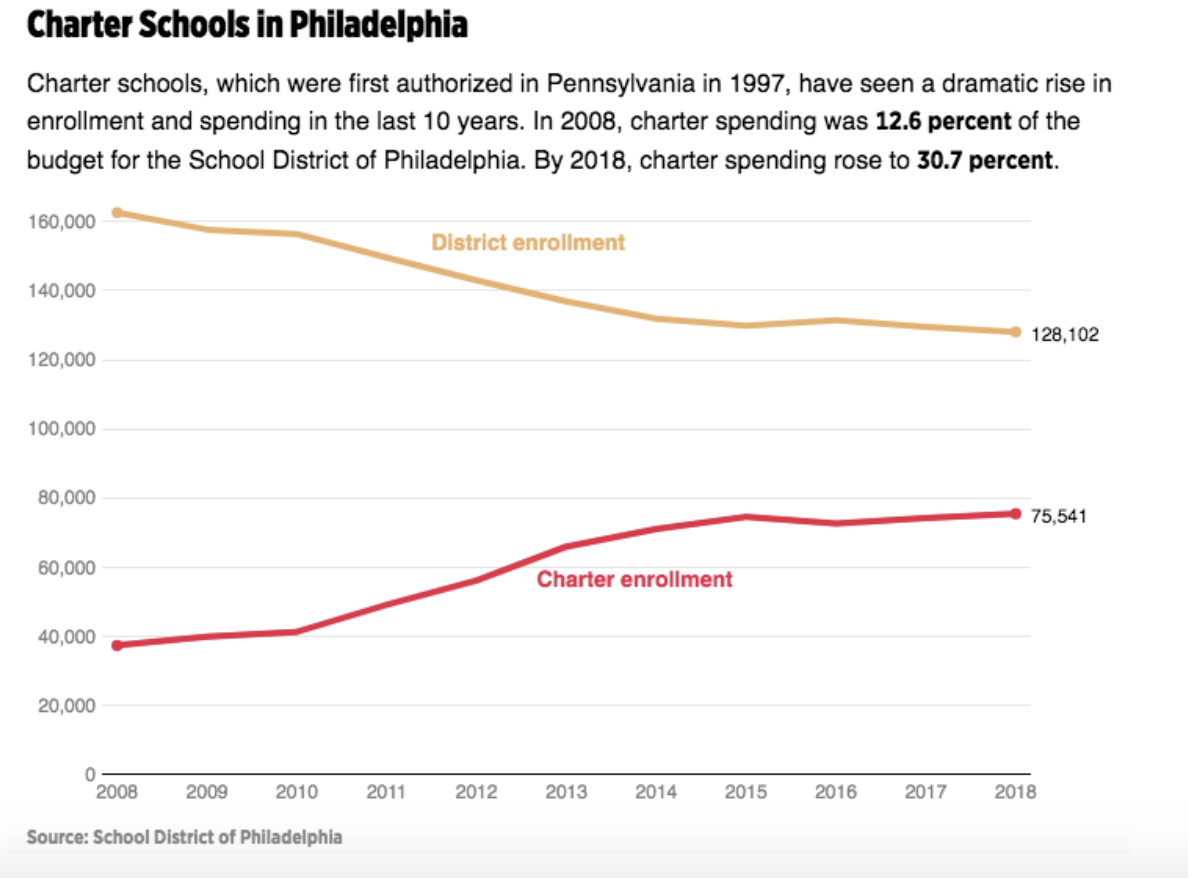

The Pennsylvania legislature ratified the state’s charter school law in 1997 to, among other objectives, “increase learning opportunities for all pupils,” “provide parents and pupils with expanded choices in the types of educational opportunities that are available within the public school system” and “hold the schools established under this act accountable for meeting measurable academic standards.”

As charter school enrollment has risen over the past decade, traditional public school enrollment has fallen. But that push-and-pull relationship is just one of a number of points of contention between charter and traditional public school advocates. Also at issue are jobs, funding, performance standards and accountability.

“The fight between charters and non-charters is a red herring, it’s a straight jobs issue — more specifically, it’s about teachers unions 100 percent and the weak politicians who listen to them,” Perry said.

A new report by the Education Law Center argues that Philadelphia’s charter schools serve wealthier and more advantaged students than the city’s traditional public schools, failing to fulfill the original charter law’s purpose of “increasing learning opportunities for all pupils.” Whereas 70 percent of students in the traditional district schools are economically disadvantaged, according to ELC’s report, just 54 percent of students in charter schools fall in that category.

Still, a recent Inquirer poll found that twice as many Philadelphia voters support charter schools as oppose them. But the same proportion as those who oppose charter schools also say they are neither good nor bad.

And now, 22 years after the charter law was enacted, Philadelphia brick-and-mortar charter schools serve around 70,000 students, roughly one-third of the city’s public school population and nearly half of Pennsylvania’s charter school population. About 42,000 of those charter students are black.

But Wednesday’s panelists pointed out at Martin’s questioning that just five of the city’s 87 charter schools — serving majority-black students — are developed, led and run by black education leaders or charter management organizations.

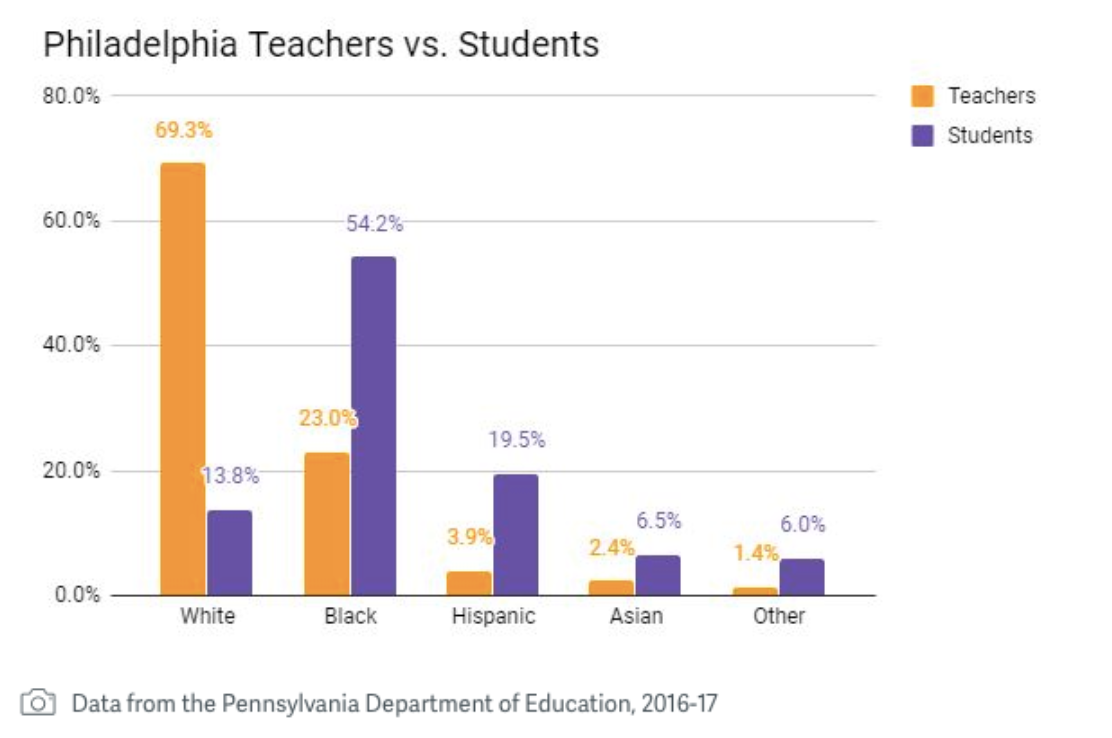

“The majority of kids in public schools today are black and brown, and you have an education reform movement that is too white,” Martin said. “African Americans want to also see us in control of schools, in control of curriculum, in control of the budgets, in control of the hiring.”

Leadership that is disproportionate to the racial makeup of student bodies is just one piece of the off-kilter scale in Philadelphia. Across the city’s traditional district and charter schools, 70 percent of teachers are white while just 23 percent are black, according to a Notebook analysis.

Much of the change that must occur comes from the need to bring the black community together to work toward lasting change for educational equity.

“One of the biggest chasms that exist for us around education reform is the chasm in the black community,” Perry said. “What’s strange is many African Americans, who are middle class, think just because they’re middle class, they’re no longer as black as the other people. We have to recognize that within our community, when we’re talking 6 percent of African-American children were deemed college ready by [the ACT], we’re talking about all black people, not just the poor ones … African-American children, by and large, are being beaten in the classroom by poor white children and immigrants who come in not speaking English.”

And that all comes back around, Akoto said, to data — to making data available and digestible for the black community and the public as a whole.

“An action item to folks from this is, how are you getting the message out about this data — making sure everyone in your neighborhood understands what this data means, not just for your children but for generations?” Akoto said. “How do we get politicians — local and at the state level — to really hear us and demand what we know we deserve?”

National partners for the tour include the American Federation for Children, EdChoice, ExcelinEd, J. Hood & Associates, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, the Progressive Policy Institute, UNCF and the Walton Family Foundation.

The Commonwealth Foundation, Excellent Schools PA, Gesu School, Mastery Schools, the Pennsylvania Coalition of Public Charter Schools and Philly’s 7th Ward were local partners for the event.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)