Inside the ‘TA to BA’ Educator Fellowship: How One Rhode Island Initiative Is Elevating Experienced Paraprofessionals — and Creating a More Diverse Teacher Force

It was past 7 p.m. and everyone on the Zoom call had already worked jam-packed days in the classroom. But still, over 90 minutes into the session, the energy was palpable: cameras on, participants speaking without hesitation and listeners nodding vigorously.

It was the weekly full-cohort meeting for the “TA to BA” fellowship, a group of 13 Rhode Island paraprofessionals studying to earn bachelor’s degrees and teaching certifications after spending years — or, in many cases, decades — in the classroom. Launched last year by a Rhode Island-based nonprofit called the Equity Institute, the program enrolls fellows in courses at College Unbound, a local higher education institution built for adult learners, providing scholarships to defray the costs.

This evening, discussion had landed on a topic near and dear to the hearts of many participants: racial diversity in the state’s teaching force.

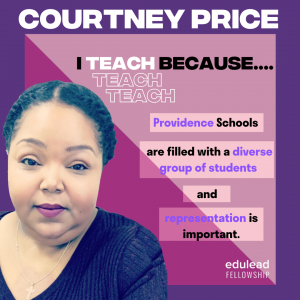

Courtney Price, a teaching assistant in Providence, unmuted herself.

“We need to see more faces like the kids that we serve,” she said, reflecting on difficult conversations she’s had with the — mostly white — teachers at her school. “These are our babies.”

The chat box popped like popcorn with affirmations and agreement.

“Well said Ms. Courtney!”

“Very well said, Court.”

More than an observation shared in an online classroom, Price’s comment also spoke to the very reason each participant was on the call that evening. All people of color, and many fluent Spanish-speakers, the group is on a mission to increase the racial and linguistic diversity of the Rhode Island teaching force.

Despite research documenting the widespread benefits to students of all races from having teachers of color, there is a stark racial disconnect between the state’s teacher and student populations — an imbalance shared nationwide.

Eighty-nine percent of Rhode Island educators are white despite over 4 in 10 learners identifying as Black, Hispanic, Indigenous or Asian. In Providence, the largest district, 93 percent of students are kids of color while 79 percent of the teaching force remains white, the exact same share as the nation on the whole. Over half of Providence students come from homes where English is not the primary language.

It’s a completely different story, however, for paraprofessionals. Approximately 61 percent of non-teaching staff in Providence schools are people of color, according to information provided by the district, and teaching assistants comprise 31 percent of that pool. At all the schools Price has worked at in her 18 years in Providence, the paraprofessional staff has always been predominantly women of color while the teaching staff has always been predominantly white people, she told The 74 — a skew echoed by TAs working elsewhere.

In addition to impacts on students, there’s also a deep wage gap. After nearly two decades in her role, Price said she earns $18.65 an hour, but would be making three times as much per year if she had worked that span of time as a classroom teacher.

The Equity Institute designed their fellowship to help people like Price transform their deep classroom experience into certifications to become full-time classroom teachers. Their model draws on examples from Connecticut, Wisconsin and California. Next door in Massachusetts, an emergency licensure program created to prevent teacher shortages during the pandemic has propelled many paraprofessionals into lead teaching roles — and has successfully moved the needle on teacher diversity in the process.

Now, nearly a full school year into the Equity Institute’s program, with rave reviews from the inaugural class, all of whom are on a path toward graduation, and with already over 60 applications for next year, early signs show their Rhode Island effort is working.

As the pandemic causes upheavals in education that have many young professionals rethinking careers in teaching, programs like the Equity Institute’s TA to BA fellowship that harness the untapped potential of paraprofessionals may be a key to building a strengthened, more diverse educator workforce.

‘Diversity is quality’

Carlon Howard, co-founder of the Equity Institute and mastermind of the TA to BA program, understands that his approach represents something of a revolution in the world of teacher preparation.

The broad goal is, “How do we change the system as a whole so that it is more inclusive?” he told The 74.

Normally, teacher licensure involves jumping through a series of hoops — each of which can present a barrier for low-income and historically underserved candidates. Applicants need to hold a bachelor’s degree and meet specific GPA requirements (2.75 in Rhode Island). They need a passing score on an exam like the Praxis Core, which has long been the target of concerns for racial bias. And, in many cases, they need to go through an approved certification program like a master’s degree in education or Teach For America, which can be prohibitive for those supporting themselves or their families.

But experts say that such requirements don’t always translate into success as a teacher. A 2017 study found mixed results when it looked for links between educators’ scores on their licensure tests and the impact they had on students down the line.

In education, the trend is to pile on “more assessments, more credentials, more degrees,” explained Constance Lindsay, assistant professor of education at the University of North Carolina and co-author of Teacher Diversity and Student Success: Why Racial Representation Matters in the Classroom. “All of those things are not necessarily related to classroom effectiveness.”

She recommends removing some of the hurdles in the licensure pathway to open the field for new applicants. Students need to see themselves in their teachers, she argues.

“Often, quality is placed at odds with diversity,” said Lindsay. She sees that view as an unfortunate misconception. “Diversity is quality.”

Credit where credit is due

Rather than test scores, studies show that it is teachers’ level of experience that more closely tracks with their impact on students. By that measure, then, paraprofessionals with over a decade in the classroom should be well-positioned to become effective teachers.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t get them very far when they seek licensure.

“They’re incredible educators,” Christine Alves, head of the Rhode Island School for Progessive Education and instructor for the TAs, said of the cohort. “But they don’t see a clear pathway to become a teacher.”

The irony is not lost on Price, who is going on 19 years as a teaching assistant. She frequently steps up to run lessons, knows how to write individual education programs for students with special needs, and once in 2019, spent two full months at the helm of a ninth-grade science course after the teacher left unexpectedly.

“I’m kinda good at what I do,” she jokes. But still, “any of the time that I’ve spent in the educator space is not considered.”

The Equity Institute’s partnership with College Unbound changes all that. The institution has a process for measuring and issuing credit for their students’ prior learning experiences. Students document their past work and present it to experts in the field. One student in the TA to BA cohort even drew on her training as an ordained minister.

“Most of our students have done some amazing stuff,” said Dennis Littky, founder and president of College Unbound. “[The prior learning evaluation process] helps them give themselves more credit for what they’ve been doing.”

Armed with a few credits already on their transcript, students in the TA to BA cohort enroll in two classes per semester, plus a full-group lab component. This term, Price is taking an applied statistics course and a course on trauma-informed teaching. The content dovetails nicely with her real-world experience.

“I’ve been able to take every piece that I’ve learned and relate it to a situation that I’ve dealt with [in the classroom],” she said.

After accruing the 120 credits necessary to earn their bachelor’s degrees, a process that takes TAs one to three years depending on their prior schooling, fellows still need to earn their teaching certifications. College Unbound has submitted an application for approval as an alternative licensure program, and though the proposal is still under review, the Rhode Island Department of Education has indicated interest in the model.

“[W]e are excited about College Unbound’s commitment to building a diverse pipeline of Rhode Island educators,” department spokesperson Emily Crowell wrote to The 74. “RIDE will be providing guidance and support with getting new educator preparation programs off the ground that reduce barriers into the profession for candidates of color.”

If the proposal falls through, fellows will use the Equity Institute’s collaboration with the Rhode Island School for Progressive Education, which is an approved institution for licensure in the state, to pursue certification after their BAs.

But still, the Praxis and GPA requirements will remain.

“The barriers,” said Equity Institute co-founder Howard, “we haven’t fully been able to knock down.”

‘There’s a desire for this’

Conceived in a note-to-self that Howard jotted down on his computer — and inspired by his own mother, a longtime paraprofessional who made life-changing impacts on the kids at her school — the TA to BA program came from humble beginnings.

At its fall 2020 launch, interest was lukewarm. The Equity Institute opened 15 seats for the fellowship and received just 16 applications.

“We practically took everybody,” Howard said, laughing.

But since then, word has gotten around. This spring, the response has been quite different. In March, their first two information sessions had over 100 sign-ups each, and the fellowship has already received over 60 applications. Those numbers send a message.

“This is needed,” said Alves. “There’s a desire for this.”

Originally planning to scale up to 30 fellows, Howard is now looking for a way to expand further. Money, though, is tight.

To launch the program, the Equity Institute received a $200,000 grant from the New Schools Venture Fund, which allowed them to support the inaugural class. Tuition at College Unbound comes to around $10,000 per year. While students can get a little over half of that sum paid for by federal Pell Grants, the Equity Institute foots much of the balance, aiming to leave each student with less than $1,000 to cover themselves. To scale up further, despite having received some additional funding since their launch, the program will have to find more cash.

A family of learners

But as Howard works behind the scenes to balance the ledger, the success of his program in the eyes of current students is undeniable.

Learning together with people who all worked years in the classroom has spurred tremendous growth, said Price. “We feed off of each other.”

“They have such shared common experience,” added Alves. “It fuels the energy. It fuels the conversation.”

The group has gelled into a cohesive learning community. Angel Soares, a fellow who works as a paraprofessional in Providence, uses one word to describe her cohort: Family.

“When we see each other, it lights our day up,” she said. “You can’t physically touch each other. But by the time you come out [of the Zoom session], you feel like you’ve been hugged. You feel like you’ve been supported.”

The group has a WhatsApp chat they use to communicate with each other. Sometimes they touch base about assignments. Other times they send new recipes they found or check in after long days.

The support comes not just from peers, but also from instructors. Howard and Alves, the professors of their lab section, double as advisors. Knowing that his fellows have a lot on their plates — in addition to working full time, many are raising families — Howard’s message is always, “Make sure that things don’t ever get too much for you,” said Soares. When she’s having a tough day, he’s there saying, “I got you. Just let me know. I’ll send a GrubHub your way or whatever you need.”

“It’s like having a brother,” Price added of her advisorship with Howard. “I always hear his voice like, ‘You can do it.’”

Now Price is on track to get her teaching certification in about a year. Other fellows, too, are on a similar timeline. Their principals, they say, chase them down at school asking when they can hire them as full-time teachers.

In the meantime, Price tells everyone she can about the TA to BA program.

“There’s a lot of people that have the same story as me,” said Price. “Given the opportunity [they] would be excellent teachers.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)