Poll Shows Support for Teaching History of U.S. Racism — With or Without Parental Consent

President Trump recently made headlines when he announced his plans to launch a new national commission to promote “Patriotic Education.” The president’s rationale for this new commission seeps out of his belief that “teachers’ focus on slavery has taught children to hate their country.”

Trump’s initiative is as a direct reaction to teachers around the U.S. using the New York Times’s 1619 Project in classrooms — a project that centers the truth about America’s history of the Atlantic slave trade in our understanding of U.S. history. Prior to launching the new commission, he first spread word of his plan to ban schools from using the 1619 Project (although the federal government does not have the power to dictate curriculum).

When speaking to reporters about the journalistic-endeavor-turned-history-curriculum, Trump argues that “the left has warped, distorted, and defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods, and lies. There is no better example than the New York Times’ totally discredited 1619 Project.”

The irony of the president’s criticisms of the 1619 Project is that Nikole Hannah-Jones and co-authors created the project to correct for the untruths that have been circulating in history textbooks for years. In 2015, a Black high school student in the Houston area noted how his history textbook described the Atlantic slave trade as an episode that brought “millions of workers from Africa to the southern United States to work on agricultural plantations.”

This type of misinformation in history textbooks has had large and detrimental effects. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center’s 2017 survey of the 10 commonly used textbooks and 15 sets of state standards, textbooks treated slavery in superficial ways, and state standards focused more on the “feel-good” stories of abolitionists than on the brutal realities of slavery. When they conducted online surveys of high school students and social studies teachers, respectively, they found that fewer than half of the students (46 percent) identified the “Middle Passage” as the transport of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to North America. Less than a quarter of students (22 percent) know that legal protections for slavery were embedded in the founding documents of the country. Meanwhile, only 8 percent of students were taught that slavery was the central cause of the Civil War.

The existing research states quite clearly that history textbooks across the United States routinely circulate misinformation on American’s history with slavery and it’s long-term effects. What we do not know is how much Americans as a whole actually support the idea of teaching history that treats slavery correctly. Is President Trump’s new effort to silence the 1619 Project something that the public wants? Or, is this simply a political move to increase support among his right-wing conservative base?

President Trump also buttresses his criticisms of 1619 under the notion that students are being unfairly exposed to the curriculum without parental consent. “Patriotic moms and dads are going to demand that their children are no longer fed hateful lies about this country,” says the president at his press conference.

However, based on a recent survey that I fielded in partnership with Professor Sally Nuamah (Northwestern University), it appears that the kind of curriculum that the 1619 Project provides is welcomed and parental consent is not a concern.

Between July 30 and Aug. 1, we fielded a nationally representative poll of 1,273 U.S. adults with the survey firm Prolific, and our instrument includes a key question that helps us answer this question. We asked respondents whether they agree or disagree that, “all schools should feature curricula that teaches kids about the history of racism in the United States.” We randomly assigned respondents into two groups. One group received the aforementioned statement for evaluation and the other group received that exact statement with the additional clause, “regardless of whether their parents consent.”

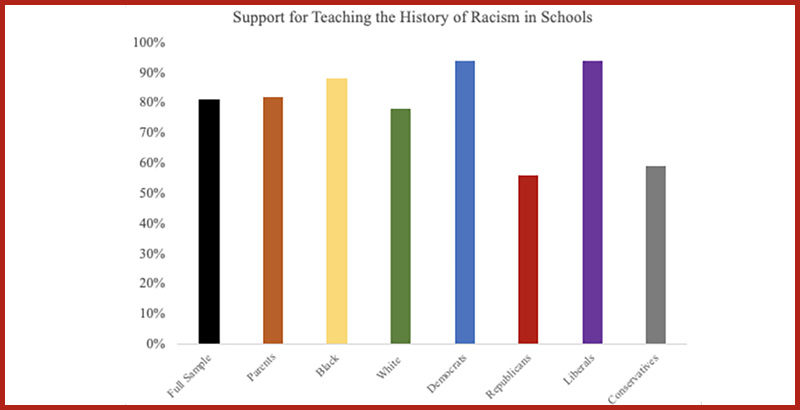

We find overwhelming support for the idea that curricula should teach kids about the history of racism in the United States — 81 percent of parents either strongly agree, agree, or somewhat disagree. Factoring in parental consent made virtually no difference, with 80 percent of respondents who received the additional clause still expressing agreement. Parents of school-aged children showed similarly high levels of support (82 percent) as non-parents (80 percent).

The most noticeable differences in support and opposition center on differences in partisan affiliation, political ideology, and racial identity. To the latter, 88 percent of Black Americans support teaching about the history of racism in schools. Meanwhile, just 56 percent of Republicans stand in agreement, as do just 59 percent of respondents who lean ideologically conservative.

As the political debate over how history should be taught in schools ensues, it is important to keep in mind where the American public stands on the issue. Again, there is overwhelming support for teaching history in a way that delivers the truth about America’s history of forcefully removing people of African descent from their home continent for a life of servitude in colonial America.

This research also offers hope towards the larger idea that the United States as a society is willing to engage in a mass reconciliation centered around the country’s original sin. This type of truthful teaching of history is important, on the one hand, because of what it means for Black students, who navigate a society very much still impacted by the Atlantic slave trade. But, to quote Frederick Douglass: “No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.”

Slave abolition — in both its original and modern forms — delivers moral healing for us all. Teaching the truth of how we were all once tied together by chains is essential towards building a future where we can be tied together by love.

Jonathan Collins is an assistant professor of education at Brown University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)