Lone Star Parent Power: How One of the Nation’s Toughest Anti-Critical Race Theory Laws Emboldened Angry Texas Parents Demanding Book Banning, Educator Firings

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Mary Lowe remembers how “heartsick” parents in her North Texas suburban community were during the pandemic when they got a close-up look at what their children were learning in school.

First they were confused. Then they got angry.

The parents expected a focus on core subjects like math and science, Lowe said, but found their children were learning about race, sexuality and LBGTQ issues. Not only were their children too young for that, she added, but the schools betrayed their trust.

“Honestly, it’s disgusting,” said Lowe, chair of the Tarrant County chapter of Moms for Liberty, a national right-leaning organization founded in January that has quickly grown to 60,000 active members focused on the “survival of America” by preserving parental rights.

Lowe’s chapter in the Fort Worth-area, formed in June, boasts 1,500 Facebook members. They’ve been showing up at school board meetings to make sure their concerns are heard.

“What this is all about is a socialist ideology being indoctrinated to the American student young enough that it would conflict with the parent or the family of origin’s ideology,” she said. “The government needs to back up. They are way out of their lane.”

Lowe and her neighbors aren’t alone in their beliefs. Conservative parent alarm over critical race theory helped clinch a win for Republican Glenn Youngkin in the bellwether race for governor in distant Virginia.

Emboldened by one of the nation’s most far-reaching anti-critical race theory laws passed in Texas in May, suburban parents have attacked school boards and districts for teaching about sexuality and racial discrimination, topics that were added amid criticism schools whitewashed history.

Their demands, sometimes through intimidation and threats, are getting attention and results.

Tension in the suburbs

Since the law passed, Texas educators have struggled to comply. In one case, a school administrator outside Fort Worth instructed teachers to offer counter-balancing stories of the Holocaust in their classroom libraries.

The list goes on. A suburban Dallas principal — accused of promoting critical race theory — was put on leave with an eye toward not bringing him back.

Another school district outside of Dallas considered removing African American Studies and Mexican American Studies.

At least one North Austin teacher packed away her classroom library all together to avoid controversy.

These clashes in Texas are centered in the suburbs, where population growth is booming, diversity is expanding and political influence flourishes. More than Republican versus Democrat, the suburbs are the root of broader “us versus them” politics, particularly in areas with a large economic or racial divide, said University of Houston political science professor Brandon Rottinghaus.

“These rapid demographic changes mean tension in traditional suburban Texas that is suspicious of change and is skeptical of real or imagined threats,” he said. “People believe (critical race theory) to be the threat to the traditional suburban way of life.”

‘Discomfort,’ ‘guilt’ and ‘anguish’

Texas was one of 28 states to push laws or state-level policies banning educators from teaching critical race theory, a new buzzword in the American education lexicon used as an all-purpose tag referring to race. Only six states ultimately passed laws to restrict the teaching of discrimination based on race or sex, although Texas passed two.

The laws target teaching concepts of discrimination. Specifically, students should not be required in a course to feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on the account of the individual’s race or sex,” according to the law. While there are no fines for non-compliance against districts, educators could lose their jobs.

Educators argue they do not teach CRT, a university-level study examining how racism is baked into policies and the legal system, but instead focus on inclusivity and race’s context in America.

‘Their thing is I’m racist against white people’

The best way Gloria Gonzales-Dholakia can explain what it’s like to be a school board member over the last year in Texas is to liken the intensity to the growing brightness of a light controlled by a dimmer switch.

Beginning in the 2020 school year, passion over issues of race lit up slowly at meetings of the Leander Independent School District north of Austin. Parents opposed a recommended diversity policy and objected to books like “Red at the Bone” by Jacqueline Woodson, about a Black teenage couple getting pregnant, and “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas about a Black teen who witnesses a police officer fatally shoot her best friend.

By February, a parent brought a pink sex toy with her to a school board meeting to protest “In the Dream House,” a memoir by Carmen Maria Machado about an abusive relationship with an ex-girlfriend.

This school year, meetings grew rowdy. Parents argued the district was breaking the law, and would crowd school board meetings carrying large signs with board members’ faces on them, calling on them to resign.

“As I walk through those front doors, it’s terrifying,” recalled Gonzales-Dholakia, a Latina board member. “There are people there with utility knives on their belts, they’ll shout at me, scream at me that I’m a racist. Their thing is I’m racist against white people. They’ll call me a communist, I’m a ‘Marxist,’ I’m a ‘traitor to the country,’ I’m an ‘enemy of the state.’ That’s the newest.”

Legislative probe of library catalogues

Last week, Texas House Committee Chairman Matt Krause, one of the most conservative Republicans at the state Capitol and a founding member of the tea party-minded House Freedom Caucus, went a step further.

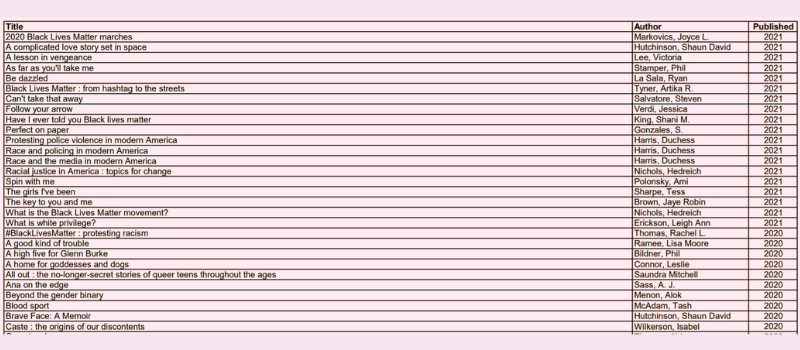

Krause, of the General Investigating Committee and a state representative from Fort Worth asked for an accounting of 850 book titles in several school districts, including novels like “Thumbelina,” alphabet picture books, and memoirs, many about the LGBTQ and African American experience, and a book about quinceañeras.

Krause wanted to know how much money the districts spend on those books and how many copies are in school libraries and classrooms. He also asked for other titles absent from the list that include sexuality, HIV, AIDS, sexually explicit images or other material that would cause students discomfort.

Battles in Texas

Pressure to oust critical race theory from Texas schools have taken a variety of forms this year, from removing books and second-guessing ethinic studies courses to disciplining educators.

Just outside of Houston, more than 400 parents in Katy signed a petition to dump a set of award-winning graphic novels about a modern-day African American pre-teen navigating life at his new mostly-white private school. Parents in September alleged “New Kid” and “Class Act,” by Jerry Craft, are “wrought with critical race theory” for teaching students “that their white privilege inherently comes with microaggressions which must be kept in check.” After a review, the district reinstated the books.

A Black high school principal near Dallas was placed on leave in August from Grapevine-Colleyville Independent School District after he was accused of teaching and promoting critical race theory after the murder of George Floyd. The school board has put in motion a plan to not renew his contract for the 2022-23 school year. The principal has appealed.

At Little Elm ISD, about 45 minutes outside of Dallas, the school board considered removing African American Studies and Mexican American Studies, arguing CRT would sow division, until the sponsor dropped the proposal during debate. In nearby McKinney, the school district canceled its participation in a nationwide youth and government program, citing a provision in the law restricting political activism and policy advocacy.

But no case compared to Southlake, a suburb 30 minutes outside of Dallas where one teacher at Carroll ISD was disciplined for having “This Book Is Anti-Racist” in her classroom after a parent complained the book violated her family’s “morals and faith.” Days after the school board voted to discipline the teacher, a school official explaining the law told educators if they have a book in their library about the Holocaust, for example, they also need a book of an opposing perspective.

The law’s sponsor has said Carroll ISD’s interpretation of the law went too far and school officials have since backtracked on that recommendation.

Parents there have also railed against a proposed diversity plan that included training and an anti-racist curriculum, ultimately delaying the proposal and overwhelmingly electing a slate of school and city officials who saw the plan as promoting with a far-left ideology that discriminates against white children and those with Christian values.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)