Equity Maps App Tracks Student Discussions for Better Understanding of Dialogue Skills, Conversation Flow and Inclusion

Educators can think of the iPad app Equity Maps as a digital ball of yarn, one that tracks data on in-class discussions and then helps students understand how their interactions during those group conversations affect those around them.

Dave Nelson, a lifelong teacher and the founder of Equity Maps, created the app as a way to “provide a tool that helps students see how they performed as a group and as a way of improving for the next time.”

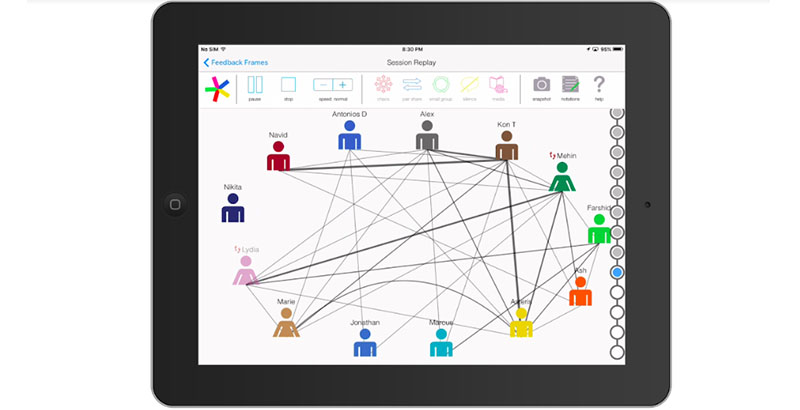

The core idea is simple, based off the old group discussion concept of passing a ball of yarn from one speaker to the next so that by the end, the group sees the web of yarn connecting speaker to speaker — often showing holes where students didn’t participate and highlighting those who may have dominated the conversation.

Equity Maps does that in digital form.

Each student in the app is displayed as an icon. As the group discussion flows, educators tap the icon of each new speaker and a line appears to create a visual representation of the conversation. At the end, educators can play back the data in actual time, or sped up to condense a 45-minute discussion into a one-minute recap, to show how the conversation flowed.

“When students can see the data and see the lines of communication that happen in a classroom, they can come to their own conclusions rather than being told this is something they need to work on,” Nelson says. “How can we go deeper to involve everyone and come to a better understanding? It is very student-driven. It teaches them how to have a conversation. That is the goal.”

Nelson, who first taught in Oregon and is now a teacher and administrator in Athens, Greece, has subscribers around the world, but the heaviest use comes from roughly 10,000 students and teachers in the United States at the middle and high school levels.

“The data Equity Maps collects provides me a greater sense of the interaction and understanding in the classroom,” says Hercules Lianos, an American literature teacher at the American Community School in Athens. “What I like most, however, is the awareness it further cultivates in the students. After Socratic seminars, we review the data and engage in a metacognitive analysis of the discussion. Students are in control, focused and conscientious of other participants, creating an etiquette of dialogue as a means to deeper understanding.”

Nelson likes to have groups set goals for equity in overall dialogue before each discussion. They can then look at the data at the end to see how they did and where they can improve. “It is a way for them to discuss what happened and it takes a little bit of the risk out of it,” he says. “They are not talking about other students; they are talking about data.”

Nelson remembers a class where, after a 20-minute discussion, the data showed there were only a couple of seconds of silence. He asked students what they thought of that, and one said it showed they knew their content and didn’t have to think much. While a few others agreed, he asked if anyone saw things differently; other students said the conversation went so fast, they didn’t have time to think about what they wanted to say and therefore weren’t able to participate.

“We were having a discussion about the importance of pausing and silence, and the group set a goal that the next time they wanted to honor the silence for students who needed it,” he says. “I’m not sure that would have come up from the students in a non-threatening way [without the data].”

The data can also demonstrate equity based on the number of students involved and how much individual students — or students of one gender — controlled the conversation. “It allows the focus on the skills of inquiry, listening, paraphrasing, engaging every voice in the classroom meaning something different than telling what you think,” he says. “It means responding to what others think, asking questions and being willing to take that risk.”

Charles Fischer, author of The Power of the Socratic Classroom, says Equity Maps’s tracking, recording and playing back student participation allows for “amazing reflection and feedback” during debriefing times. “Whole classes benefit from more equitable participation goals, while small groups can use the app to record their sessions for improvement over time,” he says.

While many teachers use Equity Maps to measure student understanding of a topic, Nelson considers improving dialogue as its primary purpose. Teachers of English learners can use the app’s recording function to allow students to go back and listen to how they speak. If a classroom has more than one iPad, the app can help a teacher monitor small-group discussions by allowing each group to record its own conversation. Instructional coaches can use the app with teachers to show how a classroom is unfolding.

Dr. Carol Brooks Simoneau, with over 20 years of experience as a teacher and reading specialist and now an in-school trainer and author, says she has been “smitten” with the app since 2016, when she saw Nelson using it as part of a workshop in Abu Dhabi.

“Our training was about adult dialogue in professional settings,” she says. “Dave described Equity Maps and demonstrated the app’s usefulness in assisting groups as they self-manage and self-monitor their offerings during conversations. Adults need help refining their dialogue in order to be high-performing group members who contribute to productive groups.” She says Equity Maps effectively harvests data to make it happen, something beneficial not only for teachers but also for students learning to become skillful at dialogue.

The app is available in the Apple Store for a one-time purchase or a premium purchase that includes future version upgrades, which Nelson is working on. This school year marks the first time in the roughly three-year history of Equity Maps that Nelson has the app available for school districts to purchase at a discounted rate if they buy more than 20 at one time.

For him, it all goes back to improving student understanding. “I have always tried to find ways to engage students in the classroom and make sure everyone has a voice,” he says. “I believe you have to see something in order to talk about it, and when you see it visibly, it makes it real and makes it less threatening to discuss.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)