Study: AI-Assisted Tutoring Boosts Students’ Math Skills

First randomized controlled trial of AI system that helps human tutors offers a middle ground in what’s become a polarized debate.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

An AI-powered digital tutoring assistant designed by Stanford University researchers shows modest promise at improving students’ short-term performance in math, suggesting that the best use of artificial intelligence in virtual tutoring for now might be in supporting, not supplanting, human instructors.

The open-source tool, which researchers say other educators can recreate and integrate into their tutoring systems, made the human tutors slightly more effective. And the weakest tutors became nearly as effective as their more highly-rated peers, according to a study released Monday.

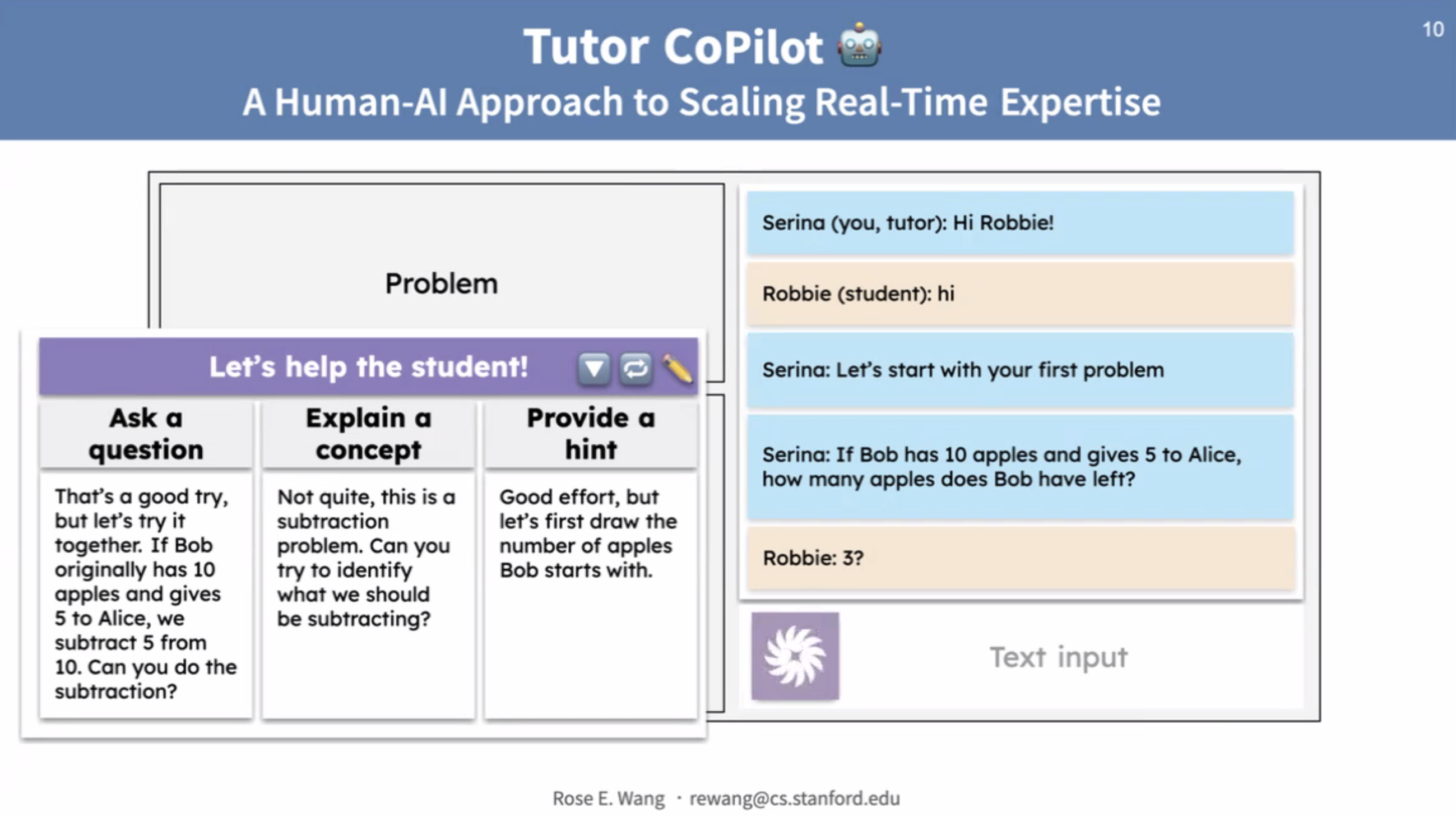

The tool, dubbed Tutor CoPilot, prompts tutors to think more deeply about their interactions with students, offering different ways to explain concepts to those who get a problem wrong. It also suggests hints or different questions to ask.

The new study offers a middle ground in what’s become a polarized debate between supporters and detractors of AI tutoring. It’s also the first randomized controlled trial — the gold standard in research — to examine a human-AI system in live tutoring. In all, about 1,000 students got help from about 900 tutors, and students who worked with AI-assisted tutors were four percentage points more likely to master the topic after a given session than those in a control group whose tutors didn’t work with AI.

Students working with lower-rated tutors saw their performance jump more than twice as much, by nine percentage points. In all, their pass rate went from 56% to 65%, nearly matching the 66% pass rate for students with higher-rated tutors.

The cost to run it: Just $20 per student per year — an estimate of what it costs Stanford to maintain accounts on Open AI’s GPT-4 large language model.

The study didn’t probe students’ overall math skills or directly tie the tutoring results to standardized test scores, but Rose E. Wang, the project’s lead researcher, said higher pass rates on the post-tutoring “mini tests” correlate strongly with better results on end-of-year tests like state math assessments.

The big dream is to be able to enhance humans.

Rose E. Wang, Stanford University

Wang said the study’s key insight was looking at reasoning patterns that good teachers engage in and translating them into “under the hood” instructions that tutors can use to help students think more deeply and solve problems themselves.

“If you prompt ChatGPT, ‘Hey, help me solve this problem,’ it will typically just give away the answer, which is not at all what we had seen teachers do when we were showing them real examples of struggling students,” she said.

Essentially, the researchers prompted GPT-4 to behave like an experienced teacher and generate hints, explanations and questions for tutors to try out on students. By querying the AI, Wang said, tutors have “real-time” access to helpful strategies that move students forward.

”At any time when I’m struggling as a tutor, I can request help,” Wang said.

She said the system as tested is “not perfect” and doesn’t yet emulate the work of experienced teachers. While tutors generally found it helpful — particularly its ability to provide “well-phrased explanations,” clarify difficult topics and break down complex concepts on the spot — in a few cases, tutors said the tool’s suggestions didn’t align with students’ grade levels.

A common complaint among tutors was that Tutor CoPilot’s responses were sometimes “too smart,” requiring them to simplify and adapt for clarity.

“But it is much better than what would have otherwise been there,” Wang said, “which was nothing.”

Researchers analyzed more than half a million messages generated during sessions, finding that tutors who had access to the AI tool were more likely to ask helpful questions and less eager to simply give students answers, two practices aligned with high-quality teaching.

Amanda Bickerstaff, co-founder and CEO of AI for Education, said she was pleased to see a well-designed study on the topic focused on economically disadvantaged students, minority students, and English language learners.

She also noted the benefits to low-rated tutors, saying other industries like consulting are already using generative AI to close skills gaps. As the technology advances, Bickerstaff said, most of its benefit will be in tasks like problem solving and explanations.

Susanna Loeb, executive director of Stanford’s National Student Support Accelerator and one of the report’s authors, said the idea of using AI to augment tutors’ talents, not replace them, seems a smart use of the technology for the time being. “Who knows? Maybe AI will get better,” she said. “We just don’t think it’s quite there yet.”

Maybe AI will get better. We just don't think it's quite there yet.

Susanna Loeb, Stanford University

At the moment, there are lots of essential jobs in fields like tutoring, health care and the like where practitioners “haven’t had years of education — and they don’t go to regular professional development,” she said. This approach, which offers a simple interface and immediate feedback, could be useful in those situations.

“The big dream,” said Wang, “is to be able to enhance the human.”

Benjamin Riley, a frequent AI-in-education skeptic who leads the AI-focused think tank Cognitive Resonance and writes a newsletter on the topic, applauded the study’s rigorous design, an approach he said prompts “effortful thinking on the part of the student.”

“If you are an inexperienced or less-effective tutor, having something that reminds you of these practices — and then you actually employ those actions with your students — that’s good,” he said. “If this holds up in other use cases, then I think you’ve got some real potential here.”

Riley sounded a note of caution about the tool’s actual cost. It may cost Stanford just $20 per student to run the AI, but he noted that tutors received up to three weeks of training to use it. “I don’t think you can exclude those costs from the analysis. And from what I can tell, this was based on a pretty thoughtful approach to the training.”

He also said students’ modest overall math gains raises the question, beyond the efficacy of the AI, of whether a large tutoring intervention like this has “meaningful impacts” on student learning.

Similarly, Dan Meyer, who writes a newsletter on education and technology and co-hosts a podcast on teaching math, noted that the gains “don’t seem massive, but they’re positive and at fairly low cost.”

He said the Stanford developers “seem to understand the ways tutors work and the demands on their time and attention.” The new tool, he said, seems to save them from spending a lot of effort to get useful feedback and suggestions for students.

Stanford’s Loeb said the AI’s best use is determining what a student knows and needs to know. But people are better at caring, motivating and engaging — and celebrating successes. “All people who have been tutors know that that is a key part about what makes tutoring effective. And this kind of approach allows both to happen.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter