Report: Charters’ Flexibility Can Enable Better Outcomes for Disabled Pupils

Schools with promising strategies hold both general education teachers and special educators responsible for all students’ growth, researchers found.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Adding to the slender but growing body of research regarding outcomes for students with disabilities, the Center for Learner Equity has released a report describing innovative strategies 29 diverse charter schools and school networks have created to meet their needs.

While some capitalize on the independent schools’ flexibility to rearrange elements of the classroom day as needed, and many have developed teacher hiring and retention strategies, the report’s author says the main takeaway is that the most promising developments are the result of cultures that hold general and special educators jointly responsible for the success of all students.

“It comes back to the idea that the whole school owns the experience of students with disabilities,” says Chase Nordengren, director of research for the nonprofit organization, which focuses on improving disabled children’s outcomes. “They make sure general education teachers feel as prepared to meet the needs of students with disabilities as special educators.”

This stands in marked contrast to the way special education services are typically delivered, with students with disabilities pulled out of regular classrooms to receive instruction and therapies that general educators frequently know little about. Though experts have long decried this approach, which flies in the face of research showing disabled children achieve more in integrated classrooms than when isolated, charter and district-run schools often resist becoming more inclusive.

To that end, the new report makes recommendations aimed at helping charter schools — which typically enjoy a high degree of autonomy in exchange for meeting academic and financial performance targets — address persistent inequities in how students with special education plans are served.

Charter authorizers — the organizations that grant schools permission to operate and oversee their performance — should consider offering the schools they supervise technical assistance and specialized expertise that standalone schools may struggle to acquire, such as teacher training and a central hiring pool. All schools, regardless of type, should find ways for general and special education staff to collaborate and collect and analyze data about students with disabilities, the researchers recommend.

Disability advocates have long complained that while over the last decade charter schools have become more accessible to families whose children need alternatives to traditional classrooms, little effort has been invested in identifying systemic improvements.

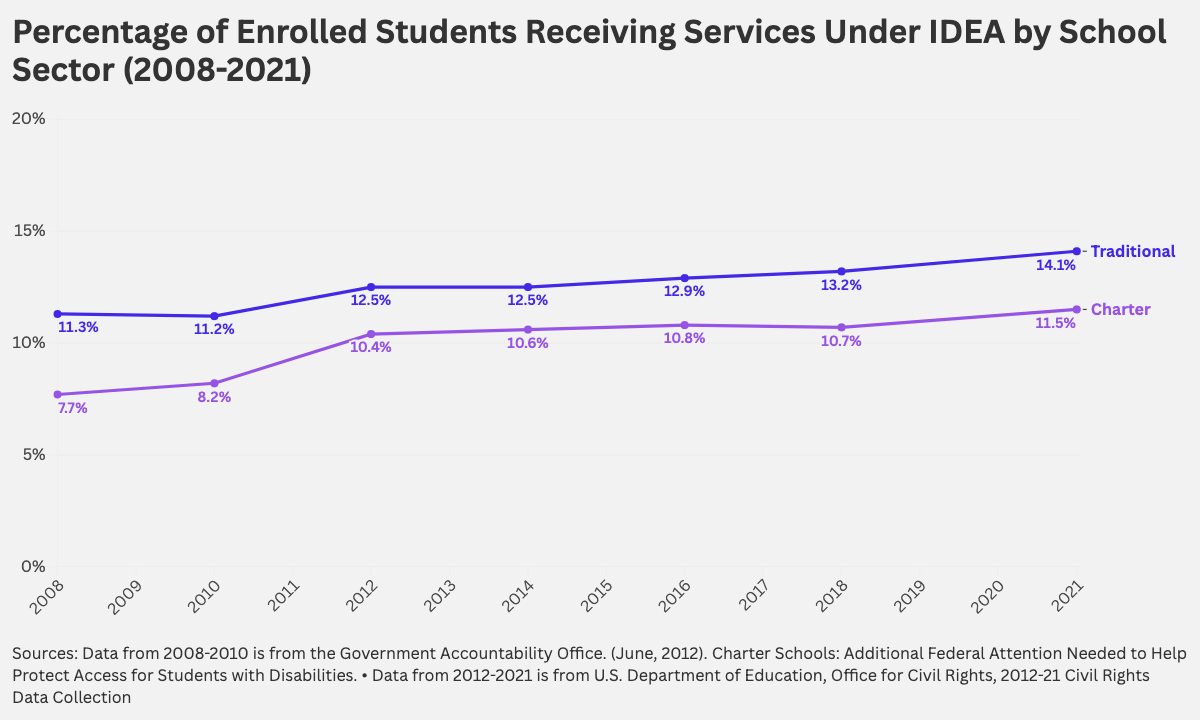

Since 2008, the number of children with disabilities attending charter schools, which have historically enrolled fewer than their district-run counterparts, has risen steadily, from less than 8% to 11.5% in 2021, according to data from the Government Accountability Office and the U.S. Department of Education. Throughout that time, charters have enrolled 2% to 3% fewer special education students than traditional schools.

But even as enrollment has increased, outcomes for children with disabilities have barely budged, the center’s researchers concluded earlier this year, following a two-year investigation. On the whole, charter schools do not outperform their district-run counterparts, even though they exist in part to develop effective ways of meeting the needs of historically underserved students. Almost no special education students are given access to college-readiness classes and programs, for example.

Following the July release of a report on those poor outcomes, the center turned its attention to a survey of schools that, intentionally or not, enroll higher-than-average numbers of students with disabilities.

The new report describes some promising strategies. One 10-year-old Atlanta-area school enrolling grades 6 to 12, Tapestry Public Charter School, was founded on the principles of a longstanding but little-used strategy called universal design for learning.

Broadly described, this means educators provide instruction in a variety of forms to enable all students — disabled or not — to engage with it. Staff have two hours a day to plan together and to collaborate with therapists, behavior specialists and other service providers.

Half of Tapestry’s 266 students receive special education services, and all core classes are co-taught by a special educator and a general ed teacher. This allows for personalized, small-group instruction in which educators can identify and address individual skills gaps.

“This both makes sure kids get the specific help they need and [aren’t] called out or singled out as needing it,” says Nordengren. “Everybody gets the support.”

A Washington, D.C., school serving 221 Black and low-income boys in grades 4 through 7, Statesman College Preparatory Academy was designed to provide structure for all of its students, including the 29% who need special education services. The school also employs a therapist who works one-on-one with staff.

“We can do personal development better than we can do professional development,” founder Shawn Hardnett told the center’s researchers. “And what we find is that people are better professionals because we’ve done personal work.”

In New York City, Mott Haven Academy is a pre-K-8 charter school founded to meet the needs of students impacted by the child welfare system. One in four students has a disability, and a third lack stable housing. Drawing on mental health and behavioral supports, the school uses the same instructional approaches with all 451 pupils, whether they qualify for special education or not.

Mott Haven uses its flexibility as a charter school to structure staff time to allow educators and disability service providers to collaborate. One example: Instead of pulling a single student out of class for extra help, a speech-language pathologist helped the child’s teachers redesign their instruction — strengthening the general education teacher’s skills.

Other common strategies include hiring general ed teachers who want to work with children with disabilities and special educators, and investing in ongoing training.

The 29 schools surveyed landed on similar strategies, but for the most part did so independently, as they sought ways to address their students’ varied challenges, Nordengren says. “What surprised me more than anything is how different these schools look from each other,” he says. “Each found a way to identify the particular needs of its students.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided financial support to the Center for Learner Equity for this research and provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter