Survey: For Most Parents, Grades Have Lost Ground as Measure of Student Progress

Due to factors like grade inflation, parents put more stock in communication with teachers to gauge kids’ performance, a large national survey found.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Parents have traditionally relied on grades to gauge how their children are performing in school.

But new data suggests that’s changing.

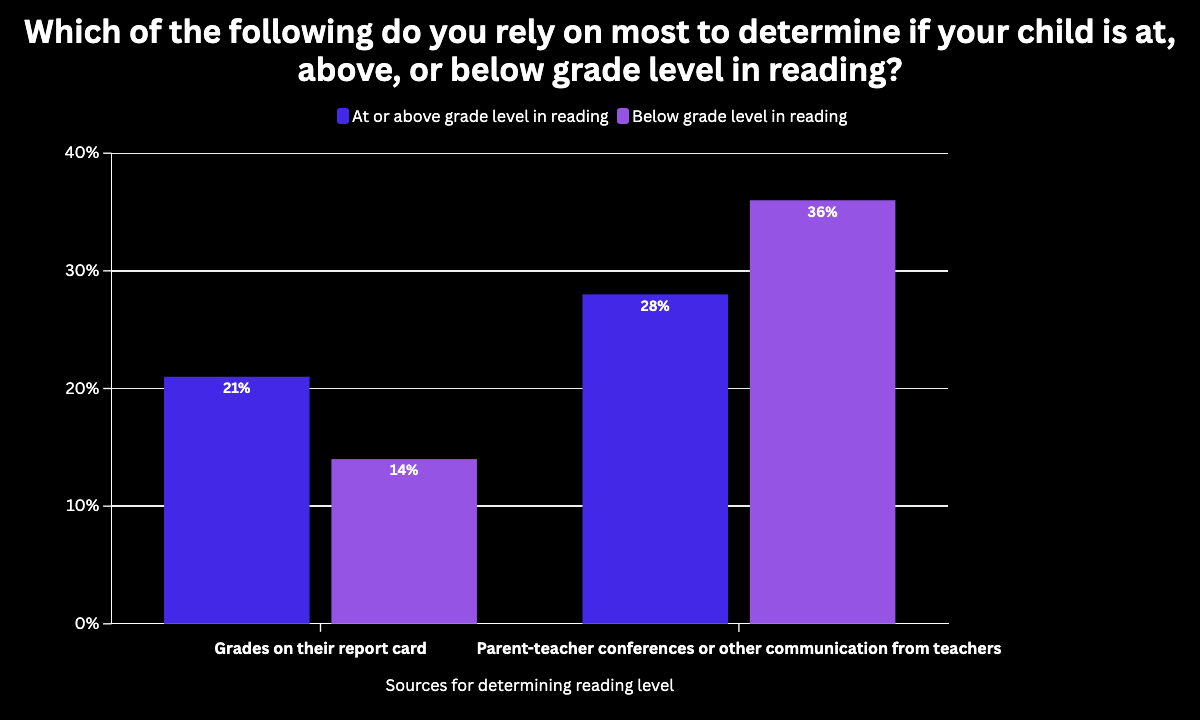

In a recent national survey of 20,000 parents, respondents said they trust communication from their children’s teachers more than any other source of information to judge whether their kids are on track. That was the case regardless of whether parents thought their children performed on grade level.

The finding came as a surprise to Bibb Hubbard, president of Learning Heroes, a nonprofit that helps parents understand student achievement data. In past research, including surveys her own organization has conducted since 2017, parents have listed grades as the primary indicator of student performance.

“For the first time, grades are not the number one factor,” she said. “Teachers really are on the front lines in terms of communicating to families about where their kids are.”

As one who urges schools to level with families about student progress, Hubbard zeroed in on that point among the trove of data that 50CAN, a national education advocacy organization, released in October.

One reason for the shift, she said, is the falling importance of grades as a dependable measure of learning. Long before COVID, research and news reports pointed to examples of grade inflation: While grade-point averages have steadily increased, objective measures of performance like ACT scores remained flat. States and districts further relaxed grading standards during the pandemic, and parents took notice. The growth of online communication apps that allow teachers to update parents throughout the year on children’s progress have also lessened report cards’ influence, Hubbard said.

“Just putting the grade in the portal is not going to be sufficient for any parent right now,” she added. “They want that connection. They want that relationship.”

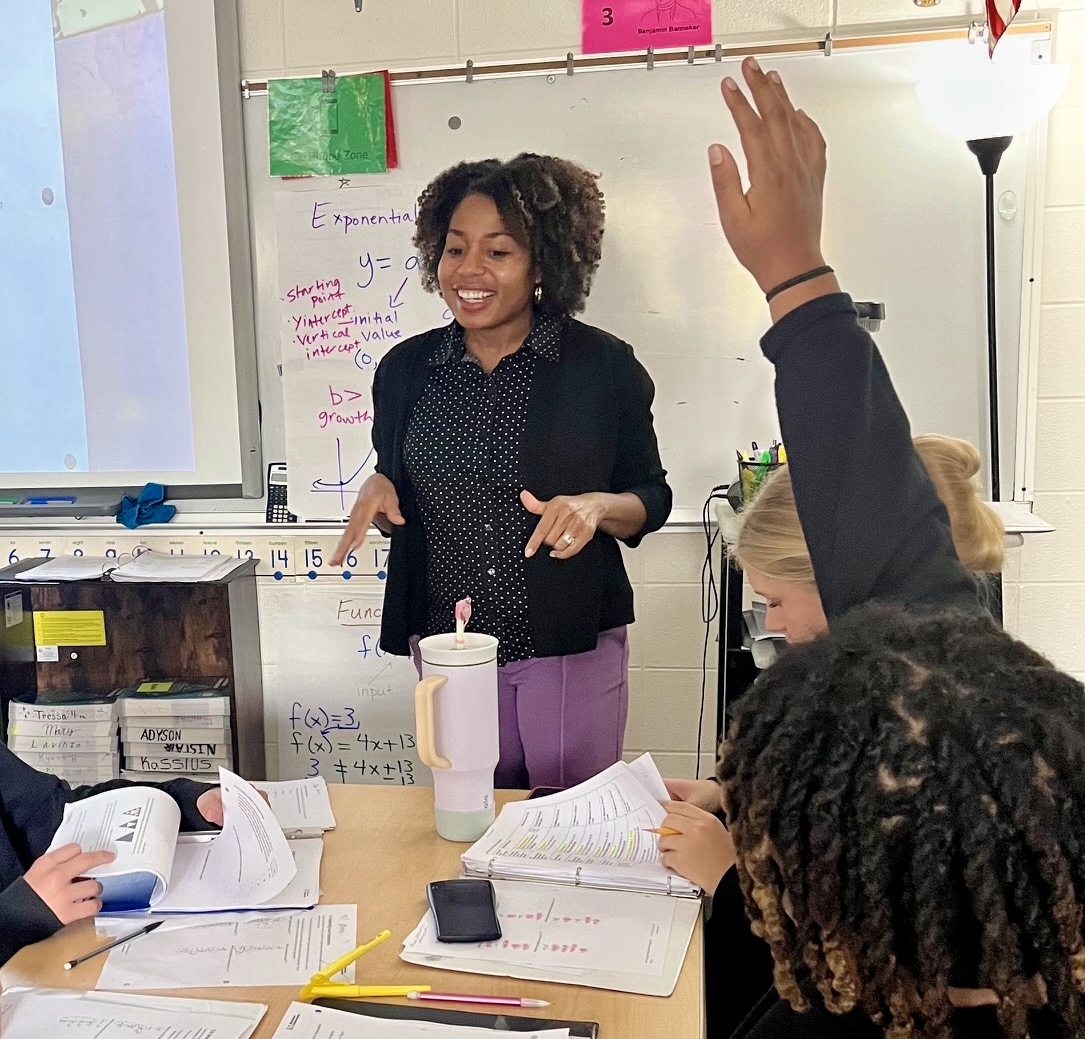

At Kickapoo High School in Springfield, Missouri, Algebra teacher Cicely Woodard said she tries to be as specific as possible when grading assignments by labeling tests with the skills students are learning — like exponents — so parents don’t have to guess. But she also leans on parents to understand why students might be struggling.

“I’ll say, ‘This is what I’m observing.’ Then I’ll be quiet and listen,” she said “I can learn so much from parents who know their children really well.”

Almost 30% of parents in the 50CAN survey said they rely on that type of communication from teachers more than any other source of information. Report card grades were second, with 20%.

Parents who believe their children are performing below grade level value that interaction with teachers even more than those who think their kids are at or above grade level, the data shows — 36 to 28%. During the 2023-24 school year, parents who thought their children weren’t meeting expectations were more likely than others to communicate with teachers outside of parent-teacher conferences, talk to their school’s principal and consult with their child’s guidance counselor.

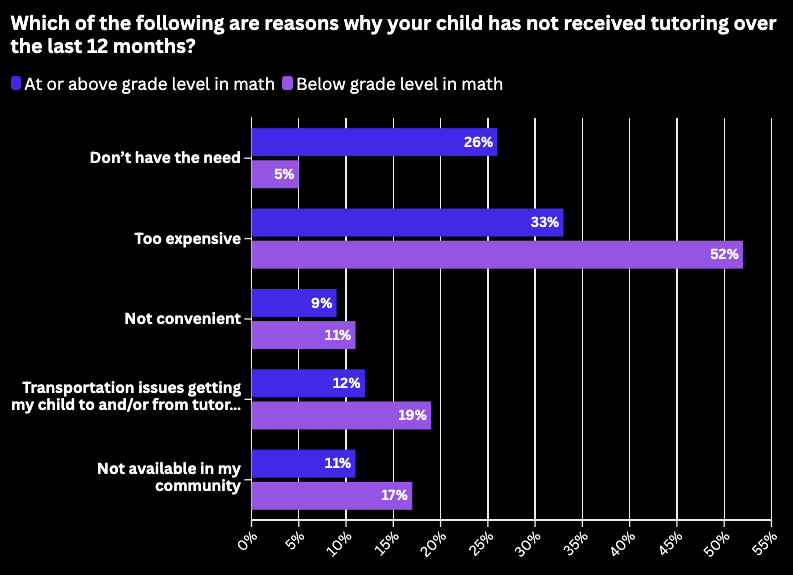

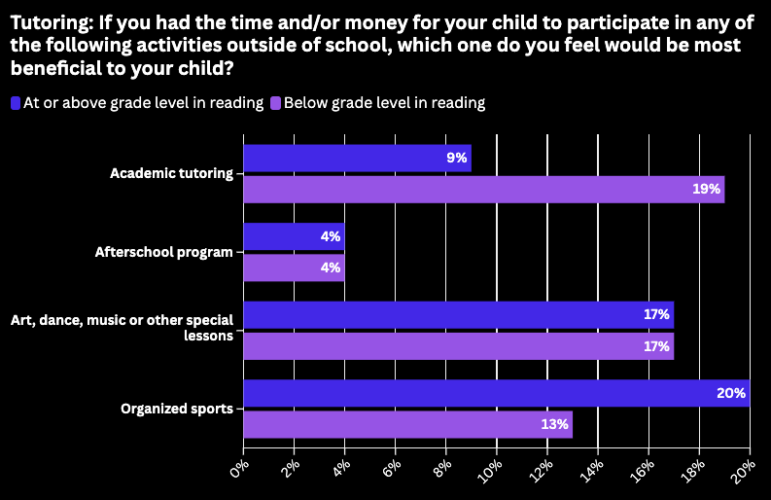

They also want their kids to get additional instruction. If they had the time or money, parents who think their children are below grade level would choose tutoring over organized sports and art, dance or music lessons, the survey showed. But a higher percentage of those parents also said tutoring was too expensive or wasn’t available in their community.

“They are engaged. They care about their kids, and they are not getting the support that they necessarily need,” Hubbard said.

Melony Watson, a mom of six in Fort Worth, Texas, said she’s barely looked at report cards in two years. She felt misled when one of her daughters kept making the honor roll even though she couldn’t read.

“I’m a proud parent, sitting there clapping and jumping up and down because my baby’s walking across the stage, getting certificate after certificate,” Watson said. But by third grade, she told her daughter’s teacher that she saw signs of a learning disability. Her daughter wrote letters and numbers backwards and out of order. “They’re like, ‘No, no, she’s just a COVID baby. She’s going to be a little behind.’ ”

Watson ultimately quit her job as a substitute teacher and homeschooled her daughter for a year before enrolling her in a different school. Now, with her children in third through 12th grade, she is in frequent contact with their teachers, especially in eighth grade algebra and ninth grade social studies.

“I get weekly updates to know what test my child has failed,” she said. “I have made myself known. If those teachers think that you don’t care, they’re not going to go the extra mile.”

‘Tipping point’

Parents aren’t the only ones who think grades provide a less-reliable predictor of success than standardized tests. Several universities, mostly Ivy league institutions, have reinstated standardized test requirements for admissions after dropping them during the pandemic.

“I do think that it is possible that we are nearing a tipping point with regard to grade inflation,” said Adam Tyner, who wrote about the issue in a recent commentary for the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute, where he is national research director. “Maybe parents are also starting to see teacher-assigned grades as a less valuable signal.”

To Hubbard, the results suggest that teachers need better training on discussing test scores with parents. Surveys of teachers conducted by Learning Heroes show educators often fear either that parents won’t believe their children are behind or that administrators will overrule their grading decisions.

“It needs to be an expectation for teachers to have ongoing communications with families — which takes time, training and support,” she said. “Otherwise, families will continue to be sidelined in being able to most effectively support their children’s learning and development.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter