Research Points to COVID’s ‘Long Tail’ on School Graduation Rates

Matriculation rates have declined in 26 states, but the full impact of the pandemic’s disruption might not be known for years.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

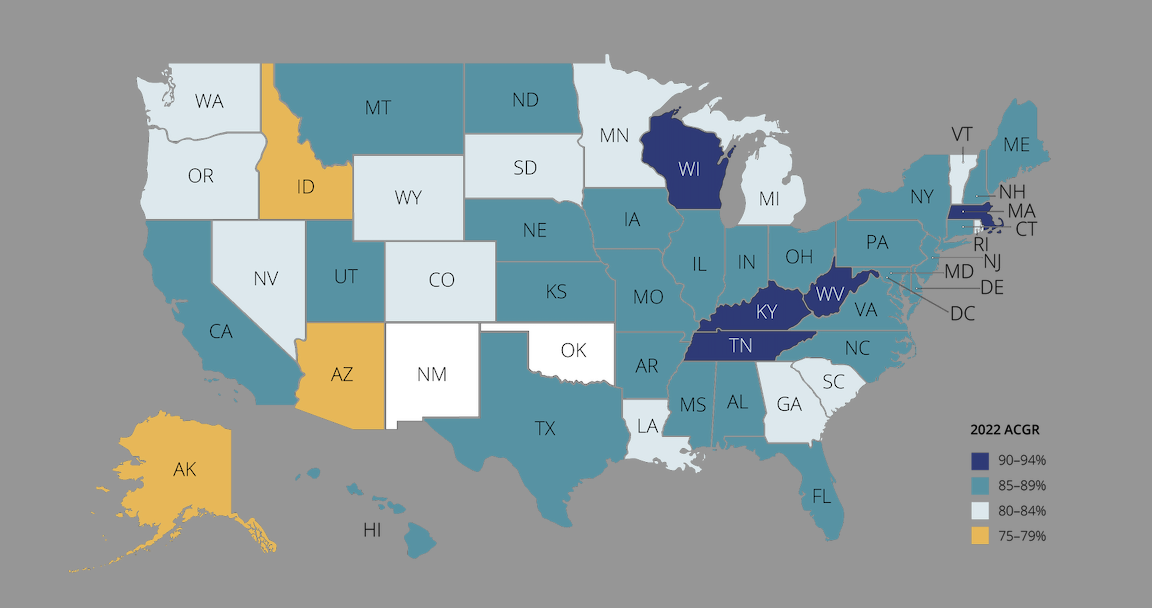

The majority of states, 26, saw declines in high school graduation rates following the pandemic, new research shows.

In 2020, for example, 10 states had graduation rates of 90% or higher, but only five did in 2022, according to Tuesday’s analysis from the Grad Partnership, a network of nonprofits working to improve student outcomes.

But the report suggests that the full impact of COVID school closures on graduation rates has yet to be realized. This year’s seniors, for example, were seventh graders when the pandemic hit in March, 2020 and likely spent much of eighth grade learning remotely or in a cycle of on-again, off-again in-person learning.

That’s why the pandemic’s effects on graduation rates and college enrollment could have a “long tail,” the report says.

“Graduating from high school is a long process,” said Robert Balfanz, director of the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, which supports the Grad Partnership. “It’s the younger kids that may be more impacted.”

The pandemic disturbed a trend of rising graduation rates that began in 2011, driven largely by gains among minorities. But an overall increase following the pandemic was due to state and local efforts to minimize the impact of the COVID emergency rather than actual educational improvement, Balfanz said.

State and local decisions to relax grading policies, accept late work and drop exit exam requirements gave the appearance that more students were meeting expectations. That’s why additional information, like whether ninth graders have earned enough credits to advance to 10th grade, chronic absenteeism data and the rates of students taking advanced courses have become increasingly valuable indicators of whether students are on track.

Meanwhile, states and districts varied widely on how deeply COVID affected families, how long schools were closed and whether they were equipped to respond to the crisis.

“We know some schools took extraordinary efforts to make sure their seniors graduated,” Balfanz said. “Others may not have had that capacity.”

Some students lacked stable Wi-Fi at home or had to go to work when parents were sick, while other families had the resources to hire tutors and form pods or attended schools that reopened in the fall of 2020.

Ohio saw the largest increase in rates between 2019 and 2022 — from 82% to 86.2%, while New Jersey saw the greatest decline, from 90.6% to 85.2%. But actions in two large states — California and New York — actually pushed the national rate to an all-time high, from 85.8% in 2019 to 86.6%.

Both states waived graduation requirements, like required courses and exams, for students. Meanwhile, New Jersey’s stricter definition of on-time graduation for students with disabilities likely contributed to the drop, the report said.

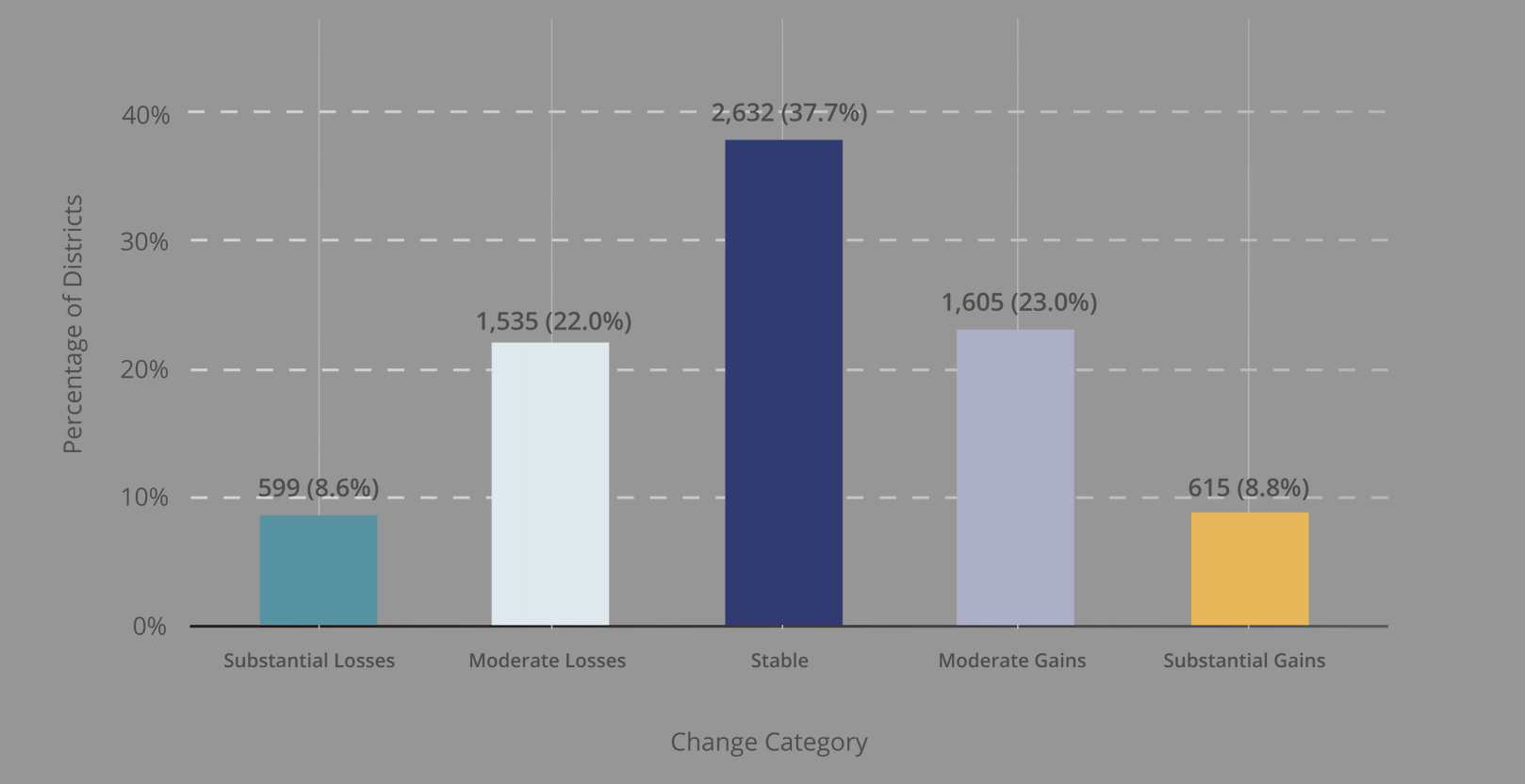

At the district level, rates varied widely. Of the nearly 7,000 districts included in the analysis, about a third saw higher graduation rates in 2022 than in 2019, while roughly the same percentage saw a decline. Rates were stable in about 38% of districts.

But the data, Balfanz said, suggests that districts should start as soon as students enter high school to make sure they’re making progress toward graduation.

As part of their state accountability systems, six states currently monitor whether ninth graders are having a successful first year in high school. Data from five of those states — Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Oregon and Washington — shows significantly fewer students were on track in 2021-22 than in 2018-19.

“These students may bear more of the brunt of the pandemic’s impact on high school graduation rates than students who experienced the pandemic as 10th and 11th graders,” the report said.

Chronic absenteeism, which remains above 25% in some states, is also tougher to get under control at the high school level than in earlier grades and is “the wild card for a prolonged period of pandemic impacts on educational attainment,” the report said.

‘Hybrid and weird’

Adam Larsen, assistant superintendent of the Oregon Community School District in Illinois, west of Chicago, remembers how much students who were seventh graders when schools shut down struggled in their freshman year.

“That eighth grade year was hybrid and weird. We had social distancing and no vaccine,” he said. “Socially, they just didn’t mature. Freshman year tried to be normal, and they weren’t ready for normal.”

The Oregon district also offers an afterschool mentoring program, called Hawks Take Flight, designed to prevent students from falling so far behind, because of absenteeism or missing work, that they can’t graduate on time.

At the weekly sessions, students talk about what’s getting in their way. If they meet their goals for the week, they earn prizes.

“Our graduation rate has been high and remains high because of the amount of support that we put in there,” Larsen said. “We have made it impossibly hard for students to fail unless they’ve chosen to fail.”

‘Make the diploma meaningful’

The way districts used their $190 billion in pandemic relief money also determined whether students received enough help to keep up with their work.

Diman Regional Vocational Technical High School, in Fall River, Massachusetts, near the border with Rhode Island, hired virtual tutors, conducted home visits and “looked at the crisis as an opportunity to use funds to support students,” said Andrew Rebello, who was principal at the school until this past August.

In 2021, without any diploma expectations waived, the school hit a record 98% graduation rate. Massachusetts, however, just changed those expectations. In the general election, voters decided to scrap the requirement that students pass exams in English, science and math in order to graduate.

The vote is a sign that the shift toward waiving high-stakes tests wasn’t limited to the pandemic.

Harry Felder, executive director of FairTest, which advocates against standardized testing, celebrated the outcome. “Parents, educators and policymakers realize that these tests fail as drivers of education that our young people need to thrive in the modern world.” he said in a press release.

But Rebello, now assistant superintendent in another district, said he thinks the state needs to add a different requirement to “make the diploma meaningful.”

The growing backlash against high-stakes testing also creates the opportunity for a fresh “conversation about what really matters for high school graduation rates,” Balfanz said.

While some research shows that getting good grades and taking rigorous courses might be greater predictors of success in college than a single test score, there are also concerns that grades no longer reflect subject mastery.

“This is a huge debate,” Balfanz said. “But, post-pandemic, we do need to revise what we expect of our kids.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter