Podcast: What a Mentorship Mindset Can Do for Student Motivation

In a special summer episode of Class Disrupted, Author David Yeager joins to discuss practical strategies for mentoring young people.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Class Disrupted is an education podcast featuring author Michael Horn and Futre’s Diane Tavenner in conversation with educators, school leaders, students and other members of school communities as they investigate the challenges facing the education system amid this pandemic — and where we should go from here. Find every episode by bookmarking our Class Disrupted page or subscribing on Apple Podcasts, Google Play or Stitcher.

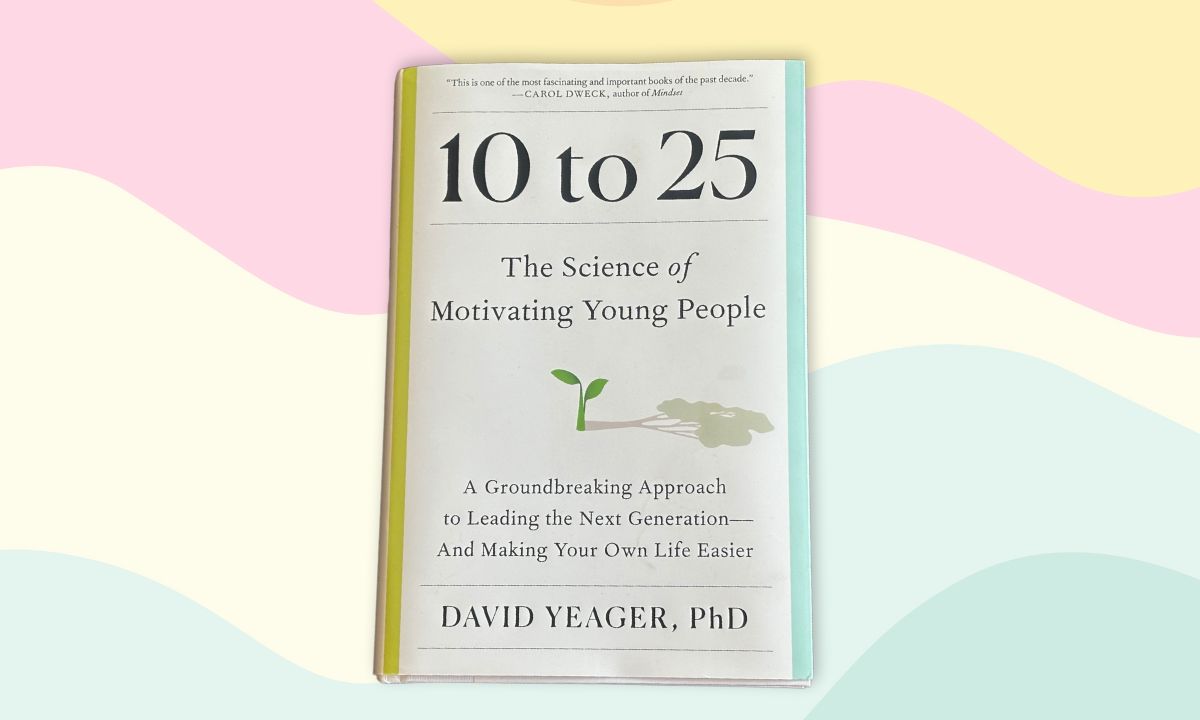

In this special summer episode, Michael and Diane are joined by David Yeager, a psychology professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author of the new book 10 to 25, which explores key insights into youth development. Together, they dive into the critical lessons highlighted in his book, including the science behind effective mentorship, the significance of transparency and practical strategies to help young people reframe and manage stress.

Listen to the episode below. A full transcript follows.

Diane Tavenner: Hey, Michael.

Michael Horn: Hey, Diane. How are you?

Diane Tavenner: I am well. This is a first for us. We are doing a special summer episode, and for good reason.

Michael Horn: We are trying to break out of the old structures of a summer break where kids go home and don’t go to school. We’re trying to break out of that model that we’ve always done in this podcast and have an important conversation about a book that is upcoming and will be out by the time this podcast is released. So, Diane, why don’t you introduce the book and our special guest?

Diane Tavenner: I’m excited to welcome Dr. David Yeager to the podcast today. He’s a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin and has a long, long list of accomplishments and works with a number of other learning scientists. I encourage you all to go look at that impressive bio. Let me just share personally that we met about a decade ago, and I have always been such a huge fan because David’s work is so applicable to schools, young people, mentoring, teachers, and parenting. He is, in my view, one of the rare researchers who not only has a background in those areas but is deeply committed to making sure his research is actually meaningful and embedded in practice. Over the years, we’ve had tons of incredible dialogues and conversations about very practical things in schools. He had a huge influence on our summit learning model when I was at Summit. I am so excited for his upcoming book called “10 to 25.”

It’s all about mentoring, which is a huge part of what I have worked on and focused on in my career. I am thrilled that you’re here with us today to have this conversation. David, welcome.

David Yeager: Thanks a lot. It’s great to be here. Diane, I think it was twelve years ago we met.

Diane Tavenner: Wow, Yeah.

David Yeager: You were my favorite person. We met at this crazy meeting where we were briefing thought leaders in education reform. The last question of that interview was, “If you could do one thing, what would it be?” Whatever I said, a week later, you’re like, “Okay. So we did that thing you said, now can you help us?” I was like, I love Diane Tavenner. She’s just gonna make it happen. So I’ve always been your admirer, and it’s great to be on this podcast.

Michael Horn: It’s not just talk with Diane, it is action.

David Yeager: Yeah, be careful what you say. She’ll do it.

Filling in the blanks on youth motivation

Diane Tavenner: Well, thank you. We are thrilled to have you. I wanted to jump in. This is going to be kind of silly, but I think it’s meaningful. Your new book introduces what I would call a Madlib activity. It’s like a fill-in-the-blank activity and the fill-in-the-blank sentences. I know you’ve asked a bunch of people to complete this, so I’m curious about the different responses you’ve gotten. It starts with this idea: The sentence, “Given that young people are ____, the best way to motivate them is ____.” I’d love to know your response to that. Also, what do you normally hear from people when you ask them to fill in those sentence starters?

David Yeager: Let me just start with the most common things I hear. The most common thing I hear is, “Given that young people are kind of short-sighted, lazy, hard to motivate, not listening to grown-ups,” or something like that. Something kind of denigrating. Then you tend to see one of two things. One is “Explain to them why all their choices now are not quite right and why they’re not aligned with their long-term best interests or motivate them with either threats or rewards.” So, “If you do this, something bad is going to happen to you,” or “If you do this, I’ll give you this nice thing.” Either bribes or threats. That’s the most common answer I see. The second most common answer I see is, “Given that young people are stressed out, overwhelmed…”

Diane Tavenner: Addicted to their phone.

David Yeager: Right. Addicted to their phones, recovering from COVID, lonely, in the middle of a mental health epidemic, etc. The best way to motivate them is to remove their demands, chop up what they’re doing into tiny steps, help them feel a sense of success, let them feel confident, don’t overwhelm them. Basically, make it easy on them to grow up. Both of those internal logics make sense, but neither of them are great. The big punchline from my book is when I started studying people who do an awesome job at motivating young people, even in the most difficult of circumstances, they complete the sentence with, “Given that young people are capable of doing incredible things that make contributions to the world, the best way to motivate them is to inspire them, sometimes to get out of their way, to run interference, so that way things don’t derail their ambitions and hopes, but really support their potential to come alive.” I like this exercise because it reveals how our beliefs about young people are intimately tied to our practices and how we deal with them. That sounds obvious when I say it, but it’s not obvious to most people. They just think, “Okay, the best way to motivate people is the following,” and they don’t question the fact that that’s a choice, and it comes from a belief system, and it’s something that could be changed.

David’s Motivation for Writing 10 to 25

Michael Horn: It’s really interesting. I’m feeling jealous at the moment because Diane’s had the chance to read the book in advance, and I will read it once it’s out. What motivated you to write this book, 10 to 25? What was your intention? What’s your hope for the book?

David Yeager: For me personally, the book comes from 15-20 years of frustration, feeling like the advice I had been given as a teacher and later that I saw in the research literature just wasn’t cutting it. It wasn’t good enough. I remember being a mediocre middle school teacher and caring so deeply for my kids and wanting to do everything for them and feeling like I never got that kind of inspiring, enthusiastic love of learning, where kids were embracing the hardest stuff and coming after class because they were curious about the topic. Then when I started doing research, I also felt like the answers I saw in the field were very… I don’t know, just not useful. It was very abstract and bland and not applicable. We’ve conducted a lot of research over the last 15 years, and part of the book is, “All right, let’s put that all in one place.”

I’m often asked about this part of my work. Some people think of me as the community college student success person, others as the purpose-in-life person, others as the youth mental health, and others as the growth mindset. I wanted all the work to be in one place, but the other thing was just an acknowledgment that there was a lot I didn’t know, and I needed to go out in the world and find great leaders who were awesome at motivating young people. The book is a combination of the science we’ve done over 15 years and original reporting on what I’ve learned from the wisdom of practice, I guess you could say.

The Mentoring Mindset

Michael Horn: Very cool. I’m curious, then. Diane teased that a lot of this book is not just about motivation and how to spark students, but a part of that is this mentoring mindset, I think you call it. I’ve certainly bought hook, line, and sinker on the importance of mentoring, but the mentoring mindset is a phrase that is unfamiliar to me. So, what is the mentoring mindset?

David Yeager: Yeah, the mentor mindset is an approach or a philosophy you take with a young person where you maintain very high standards. You’re tough, you expect a lot, but you’re supportive enough so that a young person can meet those standards. It’s not just saying, “Hey, I have super high standards, you can meet them or not,” which often ends up with maybe the top 5% doing well and everybody else struggling. It’s not saying, “I care about you, but I’m not going to ask a lot of you,” where maybe kids feel supported but they don’t grow and improve. The basic mentor mindset is high standards, and high support. It’s a simple idea.

Where does that come from? It comes from this investigation of the most successful people I could find in K-12 education, higher ed, academic research, NBA coaching, parenting, management at retail, grocery stores, management, and technology firms. I wanted to look at anyone who’s in charge of or relates to someone aged 10 to 25 in any of these domains. What do the most successful people have in common? The answer was this mentoring or mentor mindset. In the book, I describe it and also describe what’s the opposite of that. What happens if you don’t have that?

Diane Tavenner: Michael, you’ll love it because it is a two-by-two because you always have.

Michael Horn: You’re saying I’m going to feel at home is what you’re saying.

Taking an Asset-Based Approach

Diane Tavenner: You’re going to feel very at home. I love the mentoring mindset because it embodies the belief system that I’ve had for my career, this idea of high expectations and high support. Let’s just put names on the other ones that you were describing, David. There’s this enforcer mindset which is like you were describing, high expectations but no support, and this protector mindset which is high support but no expectations. One of the things I love in our conversation is you never start from a deficit mindset. You’re always an asset-based approach where you’re like, “Look, even those other two places have one of the two parts of the equation, so they’re halfway there. We just need to get the other half in there, if you will.” Say more about that.

David Yeager: Yeah, I think there are two ways in which it…

Diane Tavenner: Hopefully, I explained that properly.

David Yeager: Yeah, it was great. Later on the test, I’ll give you a high score. As a professor, I’m just walking around grading everyone. Just kidding. There are two ways in which we try to be asset-based. One is that suppose you’re in one of these off-diagonal cases, the enforcer mindset: all standards, low support; protector: all support, no standards. That’s coming from a good place and I started to talk about that. Then the second is, as you’re saying, reframing those two off-diagonal cases as you got half of it right, so just add the other half. Why do I say they’re coming from a good place? Well, I think for a long time people have felt torn. If I’m a manager, a boss, a teacher, a professor, I have a dichotomous choice between being the tough, authoritarian, dictator, kind of hard-nosed person who demands excellence. The negative consequence of that, of course, is kids and young people are crying and feeling debilitated and crushed. Most people don’t succeed.

But that is viewed as a necessary side effect of me upholding high standards. You can see how you could put your head on your pillow at night and feel good about that. It’s like, “I’m the gatekeeper to excellence and high performance, and I’m doing what I have to do, though it’s sometimes unpleasant to uphold the standard for culture or society or performance.” On the other side, where you’re very low standards but high support, what I call the protector mindset, there too, you can feel good about how you’re caring. You love young people. You’re putting their feelings and needs first. You’re being empathetic. You’re very attuned. Those are all good things to feel. The problem is that you’re also a pushover and young people don’t get anywhere. But it might feel like that’s the necessary consequence of protecting young people from the distress of this dog-eat-dog world that they can’t possibly succeed in. Both come from a concern for young people, both the enforcer and the protector. They’re just a little misguided.

The reason they’re misguided is because they’re embedded in this worldview we have about young people generally being incompetent. If you think they’re incompetent and I have to be tough, well, that’s enforcer. It’s like, “I need to maintain the standards, and I’m the last defense against the world descending into chaos.” That’s why I have to maintain rigorous standards. On the protector side, they’re incompetent, they’re weak, but that’s why I have to make up for what they lack by protecting them.

Diane Tavenner: Yeah.

David Yeager: So the mentor is like, “All right, let’s just take both of what’s good from those. You’ve got the high standards. Great. Add the support. You’ve got the support. Great. Add the standards so you can have two reasons now to feel good about yourself at the end of the day, not just one.”

The Transparency Statement

Diane Tavenner: Yeah, I love that approach. The book is filled with the science that’s behind it. One of the things I appreciate about you is it’s not only all the science and research you’ve done. You are highly collaborative, and you have an encyclopedic knowledge of all the other research in the space that everyone else has done. You are very generous in bringing those ideas into the book. We are not going to spend a lot of time on the science here today because we want to, given our audience, go to the practices that you put forward. But I will say for people who want to do a deep dive there, I’ve listened to the Huberman Lab podcast that you did. It’s 3 hours, and it’s an extraordinary deep dive in that space. So I highly recommend that for people who want to go really deep there along with the book if you want to listen. I want to shift us over to these mindset practices. They’re particularly profound here in conversation.

Honestly, when I looked at the titles of these chapters and when I started digging in, these are things that Michael and I talk about all the time on the podcast. These are cornerstones of, in our view, what redesigned schools and learning experiences need to be building on, incorporating how they need to function, essentially. We are deeply aligned in our agenda for what learning can and should look like. Let me just say off the top because our listeners will recognize these. We’ll start with transparency, which is a really interesting intro. I think you say these go from easiest to implement to probably most challenging. So we’ll talk about that. Transparency, questioning, this reframing of stress, and then purpose and belonging.

Again, our listeners have heard us talk about purpose and belonging sort of at nauseam, but we can keep talking. Let’s start with transparency because you have this very, very, I would say, easy lift that people can do, called a transparency statement. Tell us about that. What does that look like? How does that get you off on the right foot, quite frankly, in your relationship with young people?

David Yeager: The transparency statement that I write about is very simply explaining your motives whenever you are about to uphold some high standards and/or provide some support so that young people don’t interpret it in the worst possible light. That can be very short. Let’s take Uri Treisman, the world’s greatest freshman calculus professor I write about in chapter eleven. He’ll give students large intro courses in calculus, five problems where they have to find the limit of a function using L’Hopital’s rule. The thing is, most kids, when they take AP calculus, memorize L’Hopital’s rule, and then they just apply it to find the limits of functions. But the problem is that L’Hopital’s rule is not an analytic solution. It’s like a workaround.

So it doesn’t work. It breaks a lot. He’ll give students five problems, four of them L’Hopital’s rule won’t work for, and one it will. A normal teacher doesn’t do that. A normal teacher would think, “You’re a lunatic because they’re going to cry,” basically. Before he does that, he’s like, “All right, I just want you to know the reason why I’m doing this is because you guys are preparing to be mathematicians and to think mathematically. I want you to have careers long beyond this class. I don’t want you to apply math tricks. I want you to be able to take apart the math tricks, figure out how they work, and put them back together again.” He says that before they spend 25 minutes struggling. If you don’t, they would be in tears, thinking, “I’m dumb at math. I’m going to fail calculus. I’m never going to be a doctor or an engineer.” That’s where a freshman’s mind is going to go. You have to say something. In a world in which he says nothing and there’s crying, tears, and frustration, that’s not a great world. The most marginalized students are going to quit first because they’re also dealing with other stereotypes about whether they’re smart enough, etc. But in the world in which he has a transparency statement, it’s otherwise the exact same lesson and the students have the exact same great professor, but it means something totally different in that context.

That’s why it’s the easiest. You can already be awesome at mentor mindset stuff, high expectations, and high support, and you could be coming across the wrong way to your young people. Sometimes all you have to do is remind them of why you’re giving them something that’s a little unpleasant. The societal narrative currently about young people is, “Well, I shouldn’t have to explain myself, because if they weren’t such woke, wimpy idiots, then they would know that I’m here for them.” There’s a version in which people, adults and leaders, think, “I shouldn’t have to explain myself.” My answer to that is, look, for most young people, starting at the beginning of gonadarche and puberty until they’re in their twenties, that day you’re talking to them is the day on which they have the most testosterone they’ve ever had in their entire lives. That day and the next day when you do something else, that also will be the day on which they have the most testosterone they’ve ever had in their entire lives, both boys and girls.

That does all kinds of things to the brain that makes them over-interpret things that might be plausibly offensive. That’s why their head goes to this crazy place of, “I’ll never succeed,” or “You hate me,” or “This is biased,” etc. You just have to explain yourself two or three more times than you think you need to. Not because they’re too sensitive, but because the job of a young person is to figure out if they’re being taken seriously and respected. Just don’t make them guess. Just be transparent.

Diane Tavenner: Yeah. One of the things that comes up in the book is this idea that at that developmental stage, they want status and they want respect, and there’s good biological reasons for that. When we are running counter to that, we’re creating all sorts of distance between us relationally, which makes so much sense to me. I can just say from my career, I can’t tell you how many of the rigorous teachers that I knew purposefully would not have been transparent upfront because they were actually trying to scare kids or create what is essentially a threatening environment because they thought that’s what they were supposed to do with high standards. The science is pretty clear that the effect they were having was not the effect that I think they ultimately wanted.

David Yeager: Right. I mean, I think there’s this mythology of the demanding leader that is impossible to please, and it’s a little bit ambiguous if you’ve won them over. In that mythology, you’re supposed to leave people you’re leading a little bit in the dark for a while and then only at the end reveal that you cared about them all along, but they’re supposed to be afraid for nine months so that way you get optimal performance. I 100% remember feeling that way as a teacher. If I tell them too quickly that I care about them, then they’re going to take advantage of me. But that’s not what the mentor mindset leaders do.

They’re super hard, and students are often crying in the first few months of their classes in college and K-12 settings. But they’re also super transparent so that by October, or November, students can now trust that when they ask a question, Mr. Estrada—Sergio Estrada is one of the teachers I write about—”Mr. Estrada, is this problem right?” He’d be like, “I don’t know. Is it right?” Initially, students hate that. But he says, “Look, I would never deprive you of the opportunity to know that you can understand physics. I care about you too much to lower standards. So that’s why I’m asking you the question back. So given that, do you think it’s right?” He’s got to say that for a couple of months. Eventually, students know that and then they start thinking on their own, and they own their own learning. It saves him tons of time. Later in the semester, they become independent thinkers. They go on to the next course in college and can do well. He’s given them that gift of being independent, thoughtful, curious, intellectual leaders, even though it was a little rocky at first because students aren’t used to it. But you’re not going to get there if you wait till May and they hate you all year. That’s idiotic. That’s mythology.

Questioning Techniques: Asking v. Telling

Diane Tavenner: You’ve led us into the questioning technique. Some of those teachers we’re talking about, their class would also look like the professor not giving them any help or any support. That’s not what you’re talking about. Sergio and others that you profile, don’t they specifically have this strategy around asking, not telling? Tell us the dimensions and characteristics of that approach that are quite different from other folks.

David Yeager: I was really struck by the parenting coach that I followed who is almost always coaching parents to ask questions, not to tell their kids what to do. The similarities between great parenting and great teaching, great tutoring, and good management. The great manager I followed, Steph Akamoto, who was at Microsoft at the time, would do her performance reviews and ask questions like, “All right, how do you think that went?” and so on, get their opinions. Then she would say, “All right, for you to be a top 15% performer on your next performance evaluation, what’s a task you could do that’s above and beyond that would really impress everybody, and that would be something you would want to do and you want to learn?” Then they would generate two or three ideas. Then she’d be like, “Huh? All right, what are you worried about getting in the way of those things?” An example in the book is Steph’s doing a performance review when she was on the software testing unit for Microsoft. They would write manuals that would help the developers know what Windows is doing, for instance. Someone on her team was like, “Well, instead of just testing it and writing the manual, I could go talk to the engineers and fix all the goofy things with the software now, rather than have 20 pages in the manual about how the goofy thing is a workaround.” She’s like, “Okay, what would be hard about that?” “Well, the engineers don’t want to talk to a tester because I’m low status, and the manager is going to be like, ‘Stop wasting my engineers’ time.'” Then Steph would be like, “All right, would you mind if I contacted the manager and said, ‘Get off her case and let her go talk to your engineers?'” “No, that’s okay with me.”

So they formed this whole plan where her direct report could overperform and do something testers weren’t normally required to do. Steph’s out… She’s not doing it for the direct report, but she’s running interference to give her the freedom to be in the room to talk to the engineers. Six months later, her direct report is overperforming as the top 5-10% performer, gets a raise, promotional velocity, etc. But Steph didn’t do it for her. That’s what I mean by questioning. There’s a version of questioning that’s not good. If your kid comes home drunk and you’re like, “What were you thinking?” that’s not an authentic question. What you really mean is, “You were not thinking, and you’re an idiot, and you’re in trouble. I could not be madder at you.”

That’s what you mean. There are versions of questions that are just about facts. What I’m really talking about is what I call in the book authentic questioning with uptake, where it’s a legitimate question that the person could have a true answer to that, in principle, the asker doesn’t know the answer to. Second, where the question builds on some thinking the person has done. I found mentors did that a lot and did it really well, whether it was the NBA’s best basketball coach, Sergio Estrada in physics class, Uri Treisman in calculus, or Steph at Microsoft.

Reframing Stress

Diane Tavenner: It’s resonating with me on multiple levels because as I build this new product to help young people figure out what they want to do in the future, this was the cornerstone of our approach. We would ask authentic questions of them and help them discover and explore versus the traditional approaches that kind of tell you, “We have this black box questionnaire or test, and then we tell you, ‘Oh, guess what? You should be a firefighter or a mortician or whatever.'” Young people are like, “What are you talking about? That’s not me.” So very resonant. The next piece is a total reframing of stress. Especially coming out of COVID. Michael and I started the podcast during the middle of COVID and everyone, probably at the time, really swung one direction about, “People are so incredibly stressed.”

We have to completely fundamentally change our expectations and our behaviors in response to that stress. I still think there’s a belief that young people and kids are so stressed. This is where I think the protector mindset comes in a lot. The science, though, tells us something very different. We should think differently about stress and then act differently accordingly. Tell us about that.

David Yeager: This was an important chapter in the book because there’s a world in which managers are out there saying, or teachers, or professors, “I’m a mentor mindset. Therefore, I have mega hard expectations for you, and you need to suck it up and just deal with how stressful it is.” That’s not what you see the best mentor mindset leaders doing. They definitely maintain standards. They definitely imply you should stick with it. But they don’t tell you to suppress your stress or feelings of frustration, etc. Instead, they have ways of reframing the negative emotions that tend to come from pushing yourself to your frontiers and reframing them as, one, a sign you’ve chosen to do something important and meaningful. If it was easy, then anyone would do it kind of thing.

But the fact that it’s hard means that you are doing something impressive. The fact that you’re stressed often means you care about it, that it matters to you, and that’s cool to do something that matters to you. Then, second, that those worries actually can be fuel to help you do better. You see that a lot. If you look at great one-on-one tutors or even a good golf coach or tennis coach, they’re really asking you to go take on a challenge. In athletics, choose harder opponents, and if it’s tutoring, choose the harder problems and try them if you can’t master them. Second, that physiological arousal of heart racing, palms sweating, butterflies in your stomach, that’s your body mobilizing oxygenated blood to your muscles and your brain cells, and that’s helping you to be stronger and your brain to think faster and so on. Most people don’t think that way.

They think the fact that I have butterflies in my stomach and my heart’s racing means my body’s about to shut down, that my body’s betraying my goals, and it’s going to get in the way. We talk a lot about the science of reframing away from what’s called a suppression approach. So classic suppression would be, well, as a parent, “Stop crying. Stop being sad.” You just tell your kid to stop feeling the way they’re feeling. But as a teacher, what you often see is, “You’ve prepared. You shouldn’t feel stressed. You’re fine. You can do this. You should feel confident.” You see this a lot. Kids say it to each other, “Oh, you shouldn’t be stressed out.” It’s like, no, actually, you should be stressed if it matters to you and it’s legitimately hard. Reassuring you that you shouldn’t be stressed is a suppression approach. It turns out if you suppress feelings, they just come back stronger and get in the way. The protector mindset leads you to that suppression approach. You feel so bad that you feel distressed that I want you to get rid of it, and I want to get rid of it either by removing the demand or telling you to push the feelings down, you know, push them away, don’t feel stressed, etc. I tell the story in the book about a student of mine who emailed and said, “Look, my mom just died. Most important person to me in the world. I can’t possibly do the assignments for the next couple weeks.

I hope this won’t make me fail, but I’m just telling you I can’t do it.” I could tell from the tone that most of my colleagues at UT would either imply that she was lying about it and that she had to prove it or would say, “Just take an incomplete in the class,” either to save you the distress or because the teachers are worried about it being unfair to the other students in the class. That wasn’t my approach. I had been thinking a lot about this stress approach, and instead my approach was, “Look, let’s separate the intellectual difficulty of what you’re doing from the logistical difficulty. The intellectual difficulty is you have to do an awesome final project that’s very impressive, that hopefully you can talk about in your job interviews, can be on your resume, and that you’re proud of. I don’t want to take that away from you. That’s why you took my class, was to learn new stuff and do things that are impressive. Frankly, your mom cared for you and rooted for you throughout college because you were doing cool, impressive stuff.

So one way to honor your mom’s memory is to do a great final project in my class. Do I really care that you do the daily busy work that I assigned? No. That’s only there to help you get prepared to do the final project. What I did is I reduced the demands for the logistical stuff, like the busy work, and I was like, just communicate with your group, and whenever you’re ready, come back and then do your final project with them. She took two and a half, three weeks off and just kind of stayed in touch with her group, and then they did a fully kick-ass final project. They created this whole AI-based support to help teachers do empathic discipline rather than very harsh discipline. Three years ago, they did this before GPT was released, and then she talked about it in her interview, got this job for a major financial services group, and now is traveling the world on this rotational program, fast track for managers. She immigrated from Africa, is a very interesting young woman of color who is constantly trying to help improve society and culture.

I caught up with her a year later. I was like, “Did I do the right thing? Should I have just given you an incomplete?” She’s like, “No. Half my professors told me to take an incomplete, but then I couldn’t have graduated on time, and then I wouldn’t be in this financial services mentoring program.” That’s an example where if you have the belief that young people are capable of impressive stuff with the right support, then you start thinking about, sometimes you maintain the intellectual demand or the demand for the work that’s truly impressive, but the way you support them is to reduce some of the logistical demands. I think a lot of people mistake those two. They think being a hard-ass on deadlines is what it means to be demanding. But I think it’s having people own thinking and contributions. That that’s the demand. Deadlines are a means to get there.

Diane Tavenner: I love this chapter. The whole time I was reading it, I kept thinking back because you alluded to this in the beginning, David, but the first two times we met each other were arguably under very stressful circumstances that I would not trade, though. I mean, we were, in the first case, presenting our work to Bill Gates directly, and in the second case at the White House, presenting. If someone had taken those opportunities away from us, I think we would be very regretful. It was stressful. Those are stressful.

David Yeager: So stressful, but it’s stressful in a way where you have to bring your A-game. I think the challenge is to see it as a positive opportunity to perform at your peak rather than a threatening opportunity to fail publicly. When you do the latter, you’re still sweating, your heart’s racing, and you’re worried but doing poorly. But you also are like, all right, let’s go. It’s like if I’m a good surfer on a huge wave, that’s how you want to feel.

Purpose and Belonging

Diane Tavenner: So, David, with our last few minutes here, we’re going to give you the tall task of talking purpose and belonging, which are very significant. I should say the end of your book pulls all of this into whole models and approaches. Tell us the key concept here of purpose and belonging in your work.

David Yeager: I think that, as you know, 10-15 years ago, those were not concepts people talked about in education reform. It was like curriculum and interests were probably the two biggest things. The idea of a meaningful purpose, that wasn’t around. I think Bill Damon’s work brought purpose to a lot of people’s radars, and I did a lot of the early randomized experiments, but even now, I think it’s not as well known. Belonging, for a long time, was thought of as this soft self-esteem boost. Everyone needs a hug from all the world’s friends. It wasn’t taken seriously.

I think the common thread across the two is that they’re super powerful, especially for young people who are trying to make it through the world, having a sense of status and respect. Purpose, because you want to contribute something of value to the world around you. Having a meaningful purpose where it’s something beyond myself is depending on me, that’s super motivating for young people. A lot of education gets that wrong because they just make an argument about making money in the future or using this lesson plan in a job in the future, or it’s a delay of gratification, a long-term self-interest argument. I don’t think that’s ever really going to work to drive deeper learning. But the idea that right now somebody’s depending on you, having mastered something and done a good job, I think that’s really meaningful. In an enforcer mindset, you wouldn’t think of that because you’d be like, well, they’re going to choose the laziest possible way to do things no matter what. The only way we can entice them to do tedious work is through rewards, now, or delayed rewards later.

Belonging is similar in that now that it’s starting to get on the radar, more people are talking about it, but it’s still misconstrued. A lot of people think belonging is, “I’m going to give you a ‘You Belong’ sticker to slap on your laptop, and all of a sudden achievement gaps are going to disappear.” As I say in the book, you can’t declare belonging by fiat. It has to be experienced. One of the big things that has to happen is you have to help young people tell themselves a story of how difficulties could be overcome through actions that they could take. Then over time, they actually feel a sense of belonging in a community. I think that purpose and belonging go hand in hand because one way you know you’re valued by a community is when you’ve contributed something that they perceive as important to that community back in our evolutionary history. I think there’s a lot more in the book and there are stories about how you leverage those two to get deeper, more lasting, meaningful motivations rather than more frivolous things like turning education into a slot machine.

I don’t think that’s going to do it. What’s more important is appealing to a deeper purpose, a sense of connection, a sense of mattering, and so on.

Diane Tavenner: That’s awesome. There is so much more in the book. I can’t recommend it highly enough. I hope everyone will read it and ping us with questions, thoughts, and what comes up for you. Maybe at some point, we can circle back and do even more on the other pieces when we hear from our readers what they think. Michael…

Michael Horn: I was going to say the same thing. Just huge thanks first, David. Check out the book 10 to 25. I got a lot just from this conversation that has whetted my appetite, and I know many others will as well. Let’s circle back once we have some more fodder because I can tell we’re scratching the surface and you’ve hit these hot-button topics that, as you said, David, we sort of know there’s something there, but the full depth of how it’s understood is not there yet in the education field. I appreciate you writing this and joining us.

David Yeager: Absolutely.

Michael Horn: For all those listening, we’ll be back next time on Class Disrupted. Thank you again.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter