New Survey Says U.S. Teachers Colleges Lag on AI Training. Here are 4 Takeaways

Most preservice teachers’ programs lack policies on using AI, CRPE finds, and are likely unready to teach future educators about the field.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In the nearly two years since generative artificial intelligence burst into public consciousness, U.S. schools of education have not kept pace with the rapid changes in the field, a new report suggests.

Only a handful of teacher training programs are moving quickly enough to equip new K-12 teachers with a grasp of AI fundamentals — and fewer still are helping future teachers grapple with larger issues of ethics and what students need to know to thrive in an economy dominated by the technology.

The report, from the Center on Reinventing Public Education, a think tank at Arizona State University, tapped leaders at more than 500 U.S. education schools, asking how their faculty and preservice teachers are learning about AI. Through surveys and interviews, researchers found that just one in four institutions now incorporates training on innovative teaching methods that use AI. Most lack policies on using AI tools, suggesting that they probably won’t be ready to teach future educators about the intricacies of the field anytime soon.

What’s more, few teachers and college faculty say they feel confident using AI themselves, even as it reshapes education worldwide.

“All of this is so new, and it’s been happening so fast,” said Steven Weiner, a CRPE senior research analyst. A lot of coverage of AI in education, he said, “has rightly focused on what are schools and districts doing to support teachers … to get on board with AI?”

While teachers’ workplaces bear a measure of responsibility, he said, college programs should help out K-12 schools and districts. “I just think they should not have to have the whole burden of preparing teachers” to understand and work with AI.

Here are four key takeaways from the findings:

1. Most teachers college faculty are neither ready nor able to embrace AI.

Most teaching faculty are not interested in AI — and some actively avoid it. Just 10% of faculty members surveyed say they feel confident using AI, with many seeing it as a threat. Whether due to confusion or fear, they’re resistant to it, researchers found, limiting its possible integration into curricula and hampering educators’ ability to prepare preservice teachers for “AI-influenced classrooms.”

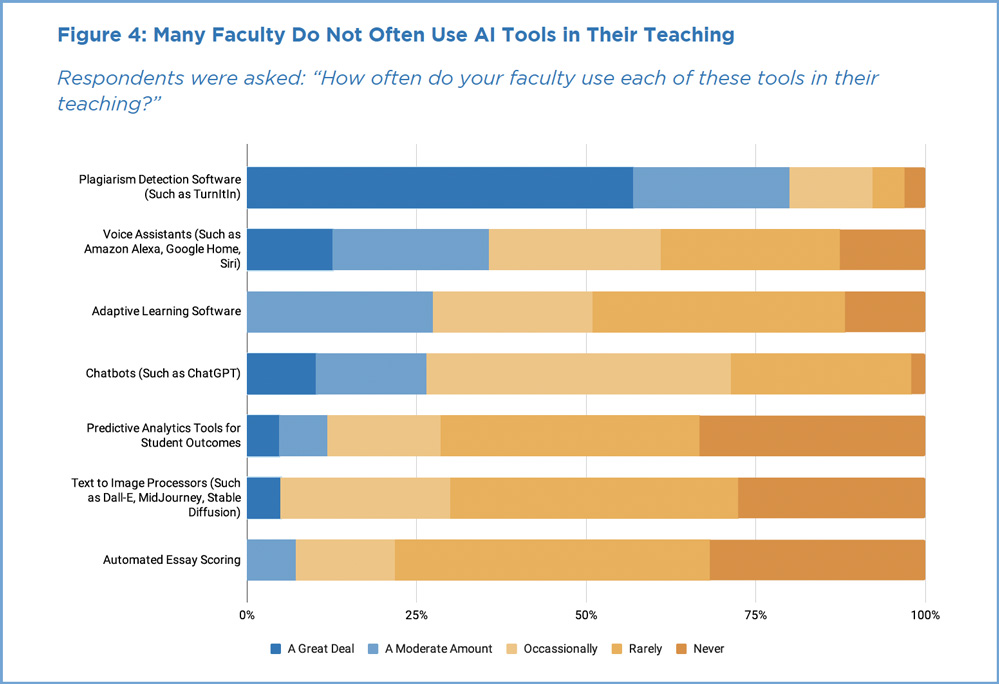

Because so few are confident with AI, most don’t use it in their instruction or effectively integrate it into their instructional practices, researchers found.

A few say faculty members remain concerned that AI “might steal their personal data, their intellectual property, or even their jobs.” One education school leader said a lot of faculty are simply “paranoid,” believing that generative AI and other technologies will soon “replace them.”

Even when faculty members are curious about AI, most are still in the early phases of learning about it. In an interview, Weiner said, “It’s up to people, I think, to learn about [AI] on their own. And if they’re the kind of people who are interested in technology, they might be into it. But the lack of any sort of systemic push for engaging with it has led to some folks just not quite understanding it.”

It's up to people to learn about (AI) on their own. But the lack of any sort of systemic push for engaging with it has led to some folks just not quite understanding it.

Steven Weiner, CRPE

2. Programs that integrate AI use it mostly to help teachers prevent plagiarism.

While nearly 59% of programs provide some AI-related instruction to preservice teachers, it mostly takes the form of coursework intended to help them prevent plagiarism.

Preservice teachers, Weiner said, “are largely being taught about AI in light of the fear of them going into classrooms where students are going to cheat.” But training on plagiarism-detection software, he said, is “super problematic” because recent research has questioned its effectiveness.

Only about 25% of programs surveyed are providing training on ways AI can support new kinds of teaching. Fewer than half of respondents said content on AI bias is offered, either in other courses or on its own.

One education school dean said a lot of faculty resistance is due to “not understanding or being able to comprehend” exactly what AI is. “I think some may look at it as just a cheating tool.”

3. A few teacher training programs show promise in integrating AI into teacher prep.

While most of the leaders surveyed couldn’t offer promising news about integrating AI into educator preparation, a few did. These institutions haven’t exactly transformed their training programs, but early efforts show promise, researchers found.

Two programs were noteworthy, they said, and worth highlighting: the University of Northern Iowa and Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, which hosts CRPE.

Northern Iowa is developing curricula for an “AI for Educators” graduate certificate. And at ASU, administrators have engaged faculty through a set of voluntary committees and outreach efforts. Actually, CRPE co-leads one of these initiatives, a cross-departmental working group focused on exploring the challenges and opportunities of AI in higher education. ASU is also partnering with ChatGPT creator Open AI to bring the capabilities of an upgraded version of the chatbot into higher education.

The report also notes that the Washington Education Association is incorporating AI into its special education teacher residency program, providing training on AI tools that help track student progress. The union is part of the Center for Innovation, Design, and Digital Learning Alliance, a network of higher education institutions pushing to leverage technology in their programs.

4. Teachers colleges need systemic, strategic investments in AI education.

Researchers concluded that the responsibility to integrate more content on AI can’t rest solely on the shoulders of “individual, self-motivated educators.” A fuller commitment to teaching about AI, they said, requires “a concerted effort and strategic action from all those involved in shaping the future of education.” To that end, schools of education should adjust their budgets to offer grants, teaching awards and other forms of recognition to “AI early adopter” faculty.

Education school deans and administrators should rely on AI experts from within their institutions, CRPE said, and look more closely at innovative work happening at other colleges and universities. They should also work with outside groups such as the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education to spread best practices and new ideas.

They also urge state policymakers to set clear expectations for teachers’ AI proficiency by revising teaching certification standards to include new competencies.

And funders, they said, should invest in preservice programs that are “already ahead of the curve” on AI, allowing these programs to grow and offer their expertise more broadly. In the meantime, they should also consider alternative training programs such as residencies and micro-credentialing that can help preservice teachers develop AI competencies and specializations.

Alex Kotran, founder of The AI Education Project, a nonprofit that offers a free AI literacy curriculum, said the survey is “a great data point that illustrates one of my big anxieties” about the future of the workforce: “How do we point students towards the jobs of the future? I think we need to talk more bluntly about the fact that four-year universities are going to be one of the weakest links in this whole strategy, in this whole process.”

We need to talk more bluntly about the fact that four-year universities are going to be one of the weakest links in this whole process.

Alex Kotran, The AI Education Project

He noted that teachers, as a group, are very unlikely to be replaced by AI in the near future — on par with “plumbers and therapists” in terms of the threat that technology plays in their future careers. So it makes sense that they’d be less than focused on it.

But he said the bigger challenge to new teachers will be to imagine how AI is going to force teacher pedagogy to evolve: “The work of being a teacher and the goals that you set for your kids is going to change, given what we understand about AI and the fact that it’s going to be so disruptive to skills and the workforce.”

The new survey, said CRPE’s Weiner, is just a first look, but he said teachers colleges appear “systemically not suited to shift as quickly as they would need — and not just to embrace AI, but to really get teachers prepared for both the challenges with AI and also the opportunities with it: to help teachers be really well prepared.”

Even if they do begin to take AI more seriously, he said, the technology is bound to change rapidly. “So what we’re really seeing is a moment where these institutions need to figure out how to become way more adaptive, way quicker.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter