Tutoring Reality Check: Exclusive Research Shows Gains Shrink as Programs Expand

Schools raced to offer tutoring during COVID, buoyed by evidence of huge benefits. But bigger programs yield smaller gains, according to a new study.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As schools struggled to overcome the chaos and academic harm inflicted by COVID, many turned to tutoring as a simple, if sometimes costly, solution. By the end of 2023, the vast majority of states were funding tutoring programs, and by one estimate, at least $7.5 billion of federal relief funds were being directed to new offerings.

The flood of resources was backed by an extensive body of evidence. Dozens of studies conducted before the pandemic showed that the positive effects of tutoring were among the largest ever seen in education policy. To help a generation of young learners return to their pre-COVID trajectory, advocates argued, there appeared to be no strategy more effective than recruiting thousands of tutors to provide regular supplemental instruction.

But a report shared exclusively with The 74 raises doubts about whether the remarkable learning gains measured in prior studies can actually be produced by the kinds of large-scale initiatives that have been launched since 2020. Released Monday, the wide-ranging overview of over 250 high-quality studies finds that as tutoring programs grow, their impact steadily shrinks.

The findings, which are predominantly drawn from pre-COVID papers, dovetail with disappointing results of some local efforts that have been undertaken in the pandemic’s wake. They also reflect the well-acknowledged reality — observed throughout education research and the social sciences more generally — that the enormous benefits sometimes seen in highly controlled settings are seldom if ever carried over to larger populations.

Study author Matthew Kraft, an economist at Brown University who has enthusiastically supported the spread of tutoring, said that the promise of the approach should not be eclipsed by the “high, and sometimes outsized, expectations” attached to it.

“We have to be realistic about how hard it is to do anything well in education out of the gate, let alone make fundamental changes to the core structures of teaching and learning,” he said.

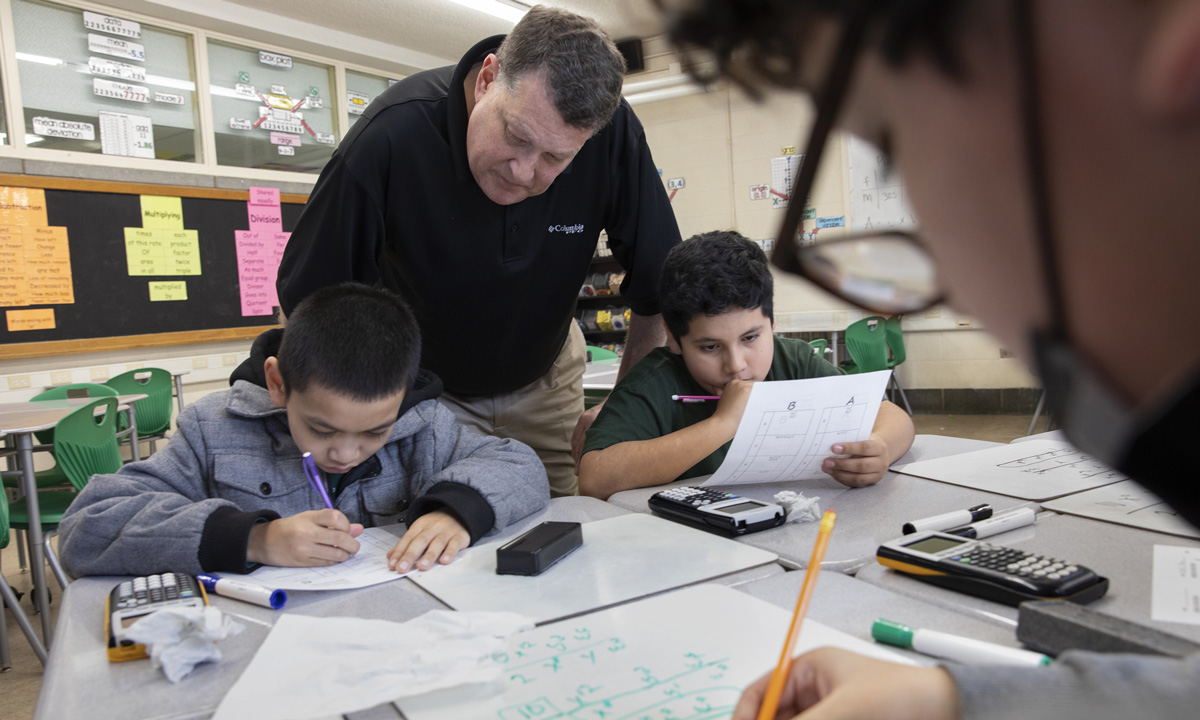

Prior estimates of the boost stemming from “high-impact” tutoring, which emphasizes one-on-one or small-group instruction in large doses, have been sizable — about as much as an entire year of reading growth for elementary schoolers, and twice that seen by high school freshmen, as quantified through standardized test scores. By comparison, the advantages conferred to students in larger interventions ranged from one-third to one-half that magnitude.

University of Virginia Professor Beth Schueler, Kraft’s co-author, argued that those outcomes remained “pretty impressive,” if not the equal of what had been measured previously.

We have to be realistic about how hard it is to do anything well in education out of the gate.

Matthew Kraft, Brown University

“Even though the large-scale programs weren’t replicating the enormous effects that you find with small-scale trials, the size of the impact that we find for these more policy-relevant studies are still quite meaningful.”

Notably, the 265 studies included in Schueler and Kraft’s analysis are all built around randomized control trials, seen as the empirical gold standard in quantitative research. They were all conducted in the countries making up the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group of wealthy, industrialized nations whose education systems are often compared against one another.

Across the entire sample of studies, average effects from tutoring were roughly equivalent to those found in earlier research reviews. But improvements to test scores shrank substantially when the authors looked only at programs enrolling between 400 and 999 pupils; they grew smaller still when restricted to those enrolling more than 1,000.

Robert Balfanz, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, observed that the early hype promoting tutoring as a “silver bullet” for COVID-related learning loss was destined to be deflated when school districts began leveraging them to reach thousands of struggling students. Still, he added, even high-enrollment efforts delivered important growth to children.

“This study just shows the reality that [tutoring] is a very effective intervention, but it’s going to take a lot of time and patience and learning to get it to work at scale,” said Balfanz, who has contributed to the U.S. Department of Education’s effort to recruit 250,000 tutors and mentors to work in schools. “Even then, scale is always going to diminish what you can do for a smaller group.”

An issue of scale

Emerging research on COVID-era tutoring initiatives has attested to the complexities facing state and district leadership.

Kraft himself released a study last month of Nashville’s program, which was established in 2021 and has grown to incorporate about 10 percent of the district’s total students. Over its first two years in operation, students’ reading performance has improved only modestly, with no corresponding gains in math. Another low-touch experiment, targeting middle schoolers in suburban Chicago, detected only a slight upturn in standardized test scores from a handful of tutoring sessions offered over Zoom.

But some advocates caution that it may be premature to measure the influence of tutoring systems that only got underway during a public health emergency. Buffeted by school closures and an uncertain budgetary picture, the initial transition to tutoring was rocky in many areas. Districts found it challenging to coordinate with families who had disengaged from schools, and an ultra-hot labor market made tutoring recruitment especially difficult.

Ashley Bencan is the chief operating officer of the New Jersey Tutoring Corps, which launched as a pilot in the summer of 2021. Since then, the organization has grown to partner with 10 district and charter school partners in over 30 locations. But even buoyed by federal and state funding, Bencan said, local schools have struggled to build up tutoring systems on top of their typical organizational demands.

This study just shows the reality that (tutoring) is a very effective intervention, but it's going to take a lot of time and patience and learning to get it to work at scale.

Robert Balfanz, Johns Hopkins University

Even collecting data on which students participate in tutoring — a vital step in determining whether the efforts actually work, Bencan said — can test the capacity of both school districts and state education agencies.

“If you’re juggling all the different things you have to work on to kick off the school year — reviewing data, grouping kids, filling positions — they have to meet those basic needs first, and only then think of what else they can do,” she said. “Tutoring isn’t designed to meet those basic needs, and we need to think about how we make it part of a school’s model.”

The logistical challenges of shoehorning tutoring into already-packed school schedules, finding sites where sessions can occur, and connecting families with tutors, can be considerable. Though Kraft and Schueler write that the design of successful tutoring programs can be effectively duplicated at a larger scale, they also find that implementation quality sometimes suffers in the course of expansion. Polls of district leaders have revealed that larger schools consistently saw lower participation rates from students, and only about one-sixth of principals in one survey reported that they had faced no barriers in providing tutoring.

Encouragingly, Kraft and Schueler’s analysis suggests that some program structures can withstand the pressures of scale. If the programs conducted in-person tutoring during school hours, featuring a student-tutor ratio of no more than 3:1, and met at least three times each week (along with other conditions), their effects were more robust with larger numbers of students. While the average impact for a program serving 100–399 pupils was 42 percent smaller than one serving less than 100, those employing the high-quality practices listed above saw their effects diminished by just 18 percent.

We are finding suggestive evidence that those implementation challenges are real, and policymakers need to think about how to get that stuff right.

Beth Schueler, University of Virginia

Schueler said the diminished, though still significant, effects of scaled-up tutoring may simply suggest that policymakers have underestimated both the scale of learning loss and the hurdles to manufacturing new learning assets from scratch.

“We are finding suggestive evidence that those implementation challenges are real, and policymakers need to think about how to get that stuff right.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter